Книги

Putnam

J.Bruce

British Aeroplanes 1914-1918

672

J.Bruce - British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 /Putnam/

A.D. Scout, the Sparrow

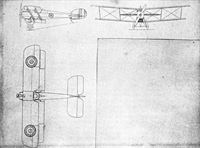

THE A.D. Scout, or Sparrow, was designed in 1915 by Harris Booth and was intended to be an anti-Zeppelin fighter. The armament was to have been a Davis recoilless quick-firing gun, a weapon in which the Admiralty were then interested.

The Sparrow was a single-engined pusher biplane of unusual appearance. Sketches of a wind-tunnel model depict a two-bay biplane of fairly large gap, with the nacelle attached to the upper wing: it appeared that the spars of the wing were attached to the underside of the upper longerons of the nacelle. An enormously tall undercarriage was necessary, but the track of the wheels was absurdly narrow. Presumably it was hoped that the widely separated twin tail-skids would provide sufficient ground stability.

The tail-booms were parallel in plan and elevation, and supported a single tailplane of great span. There were two fins and rudders.

The nacelle was an ugly, angular affair which had obviously been designed round the gun: the weapon was mounted on the floor of the nacelle, and the barrel protruded two feet in front. The engine was an 80 h.p. Gnome rotary mounted at the rear of the nacelle. The pilot sat well forward of the wings and must have had an excellent all-round view from his cockpit.

Four A.D. Scouts were ordered - two from the Blackburn company and two from Hewlett & Blondeau. It is uncertain whether all were built, but at least one was completed and was flown at Chingford. The Sparrow turned out to be considerably overweight, and on test it proved to be unsatisfactory and tricky to fly. It was quickly abandoned.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturing Contractors: The Blackburn Aeroplane and Motor Co., Olympia, Leeds, Yorkshire. Hewlett & Blondeau, Ltd., Leagrave, Bedfordshire.

Power: 80 h.p. Gnome.

Approximate Dimensions: (Derived from drawings of a wind-tunnel model.) Span: upper 32 ft 4 in., lower 33 ft 5 in. Length: 22 ft 9 in., 24 ft 9 in. over gun. Height: 10 ft 3 in. Chord: 4 ft 6 in. Gap: 5 ft 9 1/2 in. Stagger: 1 ft 7 in. Dihedral: 3 30'. Span of tail: 21 ft. Wheel track: 2 ft 7 in. Track of tail-skids: 11 ft 2 in. Airscrew diameter: 9 ft.

Serial Numbers: 1452-1453: ordered from Hewlett & Blondeau under Contract No. 38552/15. 1536-1537: ordered from Blackburn.

THE A.D. Scout, or Sparrow, was designed in 1915 by Harris Booth and was intended to be an anti-Zeppelin fighter. The armament was to have been a Davis recoilless quick-firing gun, a weapon in which the Admiralty were then interested.

The Sparrow was a single-engined pusher biplane of unusual appearance. Sketches of a wind-tunnel model depict a two-bay biplane of fairly large gap, with the nacelle attached to the upper wing: it appeared that the spars of the wing were attached to the underside of the upper longerons of the nacelle. An enormously tall undercarriage was necessary, but the track of the wheels was absurdly narrow. Presumably it was hoped that the widely separated twin tail-skids would provide sufficient ground stability.

The tail-booms were parallel in plan and elevation, and supported a single tailplane of great span. There were two fins and rudders.

The nacelle was an ugly, angular affair which had obviously been designed round the gun: the weapon was mounted on the floor of the nacelle, and the barrel protruded two feet in front. The engine was an 80 h.p. Gnome rotary mounted at the rear of the nacelle. The pilot sat well forward of the wings and must have had an excellent all-round view from his cockpit.

Four A.D. Scouts were ordered - two from the Blackburn company and two from Hewlett & Blondeau. It is uncertain whether all were built, but at least one was completed and was flown at Chingford. The Sparrow turned out to be considerably overweight, and on test it proved to be unsatisfactory and tricky to fly. It was quickly abandoned.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturing Contractors: The Blackburn Aeroplane and Motor Co., Olympia, Leeds, Yorkshire. Hewlett & Blondeau, Ltd., Leagrave, Bedfordshire.

Power: 80 h.p. Gnome.

Approximate Dimensions: (Derived from drawings of a wind-tunnel model.) Span: upper 32 ft 4 in., lower 33 ft 5 in. Length: 22 ft 9 in., 24 ft 9 in. over gun. Height: 10 ft 3 in. Chord: 4 ft 6 in. Gap: 5 ft 9 1/2 in. Stagger: 1 ft 7 in. Dihedral: 3 30'. Span of tail: 21 ft. Wheel track: 2 ft 7 in. Track of tail-skids: 11 ft 2 in. Airscrew diameter: 9 ft.

Serial Numbers: 1452-1453: ordered from Hewlett & Blondeau under Contract No. 38552/15. 1536-1537: ordered from Blackburn.

A.D. Seaplane Type 1000

BRITISH experiments in dropping torpedoes from aircraft began in 1913, and had from their inception the blessing of Captain Murray F. Sueter (later Rear-Admiral Sir Murray Sueter, C.B.), the Director of the Air Department of the Admiralty.

In 1914, Harris Booth of the Air Department designed an enormous twin-float seaplane which was intended to be used as a bomber or torpedo-carrier. When it appeared it was the largest aeroplane of any type which had been built in Britain. It was powered by three 310 h.p. Sunbeam engines, two of which were installed as tractor units at the forward ends of the twin fuselages. The third engine was mounted at the rear of the central control cabin (which was much too imposing a structure to be called a mere nacelle) and drove a pusher airscrew. All three engines had cowlings which were remarkably ugly and cumbersome. The control cabin looked uncommonly like a domestic greenhouse, and was little better streamlined. The machine was to have had a crew of five.

The serial number 1000 was provisionally allotted for the type which, in accordance with the Admiralty practice of the time, thereupon became known as the Type 1000.

It is believed that seven examples were ordered, but only one, No. 1358, was completed. Construction was undertaken by J. Samuel White & Co., Ltd., of Cowes, the makers of the Wight seaplanes; and consequently the A.D. 1000 has been wrongly described as a Wight type.

It was not a success. Its clumsy appearance rightly betokened excessive structural weight, and its floats were too flimsy: they were unable to withstand even a slight sea.

The A.D. Type 1000 was abandoned, and probably ended its days at Felixstowe. It was there in the summer of 1916. In his book From Sea to Sky, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Longmore wrote of it:

“Another boat of weird design had been delivered some time before; it looked like a floating conservatory with two floats and a double fuselage and three engines; but it was evidently not very popular for it had stayed in its shed ever since.”

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: J. Samuel White & Co., Ltd., Cowes, Isle of Wight.

Power: Three 310 h.p. Sunbeam.

Dimensions: Span: 115 ft.

Serial Numbers: 1000: ordered under Contract No. C.P.01516/14. 1355-1360. No. 1000, Nos. 1355-1357 and Nos. 1359-1360 were not delivered.

BRITISH experiments in dropping torpedoes from aircraft began in 1913, and had from their inception the blessing of Captain Murray F. Sueter (later Rear-Admiral Sir Murray Sueter, C.B.), the Director of the Air Department of the Admiralty.

In 1914, Harris Booth of the Air Department designed an enormous twin-float seaplane which was intended to be used as a bomber or torpedo-carrier. When it appeared it was the largest aeroplane of any type which had been built in Britain. It was powered by three 310 h.p. Sunbeam engines, two of which were installed as tractor units at the forward ends of the twin fuselages. The third engine was mounted at the rear of the central control cabin (which was much too imposing a structure to be called a mere nacelle) and drove a pusher airscrew. All three engines had cowlings which were remarkably ugly and cumbersome. The control cabin looked uncommonly like a domestic greenhouse, and was little better streamlined. The machine was to have had a crew of five.

The serial number 1000 was provisionally allotted for the type which, in accordance with the Admiralty practice of the time, thereupon became known as the Type 1000.

It is believed that seven examples were ordered, but only one, No. 1358, was completed. Construction was undertaken by J. Samuel White & Co., Ltd., of Cowes, the makers of the Wight seaplanes; and consequently the A.D. 1000 has been wrongly described as a Wight type.

It was not a success. Its clumsy appearance rightly betokened excessive structural weight, and its floats were too flimsy: they were unable to withstand even a slight sea.

The A.D. Type 1000 was abandoned, and probably ended its days at Felixstowe. It was there in the summer of 1916. In his book From Sea to Sky, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Longmore wrote of it:

“Another boat of weird design had been delivered some time before; it looked like a floating conservatory with two floats and a double fuselage and three engines; but it was evidently not very popular for it had stayed in its shed ever since.”

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: J. Samuel White & Co., Ltd., Cowes, Isle of Wight.

Power: Three 310 h.p. Sunbeam.

Dimensions: Span: 115 ft.

Serial Numbers: 1000: ordered under Contract No. C.P.01516/14. 1355-1360. No. 1000, Nos. 1355-1357 and Nos. 1359-1360 were not delivered.

A.D. Navyplane

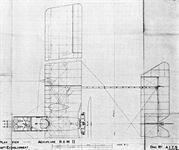

THE Navyplane was a two-seat pusher biplane floatplane sponsored by the Air Department of the Admiralty in 1916, and intended for reconnaissance and bombing duties. It was designed by Harold Bolas of the Air Department in collaboration with Messrs R. J. Mitchell and Richardson of the Supermarine Aviation Works, Ltd., to which company the construction of the machine was entrusted.

Eight weeks after the drawings were received by the Supermarine company the Navyplane was completed, an achievement which brought the manufacturers a letter of appreciation from Commodore Murray F. Sueter. Serial numbers were allotted for seven machines but only one was built. The Navyplane’s test flights were carried out in August, 1916, by Lieutenant-Commander John Seddon.

Structurally the Navyplane was a two-bay biplane with the tail unit supported on four tail-booms, and its most remarkable feature was its monocoque nacelle which, complete with seats and floor-bearers, weighed no more than 80 lb. The nacelle had a sectional glass screen which was led round the nose from the forward windscreen to a point under the pilot’s seat; this gave the crew a good forward and downward view. The Navyplane carried wireless, and the observer had a Lewis gun on a special flexible mounting. The nacelle was mounted mid-way between the wings. The wings themselves were made in three parts and only the outer portions were rigged with dihedral. The tailplane was attached to the upper tail-booms and was of the inverted camber type.

The main floats were pontoon structures and were connected horizontally by only one cross-bar. Each of the twin tail-floats had a water-rudder.

The Navyplane’s original power-plant was a new type of radial engine, the 150 h.p. Smith Static. The design of this engine was brought to England in January, 1915, by an American, John W. Smith, who succeeded in interesting the Admiralty in it almost immediately. The Smith Static was a ten-cylinder single-row radial engine which had offset connecting rods bearing alternately on the cranks of a two-throw crankshaft. The engine must have been reasonably successful. It was tested on the bench and in the air to the satisfaction of the Admiralty. A contract for its production was given to Messrs Heenan & Froude, but only a few were delivered before the Armistice.

The Smith engine was installed quite neatly in the A.D. Navyplane but was later replaced by a 150 h.p. A.R.I. rotary engine. The reason for the change is uncertain, but difficulty may have been experienced with the cooling of the radial. With the A.R.I engine the Navyplane was tested in May, 1917, but with no military load and no observer the performance was very poor.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: The Supermarine Aviation Works Ltd., Woolston, Southampton.

Power: 150 h.p. Smith Static radial engine; later, 150 h.p. A.R.I rotary engine.

Dimensions: Span: 36 ft. Length: 27 ft 9 in. Height: 12 ft 9 in. Chord: 5 ft. Gap: 6 ft 6 in. Stagger: nil. Span of tail: 15 ft 6 in. Airscrew diameter: 8 ft 10 in.

Areas: Wings: 364 sq ft.

Weights (lb) and Performance:

Engine Smith Static A.R.I

Date of Trial Report - 15 May, ’9'7

Weight empty 2,100 2,042

Military load - nil

Crew - 180

Fuel and oil - 328

Weight loaded 3,102 2,550

Maximum speed (m.p.h.) at 2,000 ft 75 64-5

Climb to 2,000 ft - 30 min

Service ceiling (feet) - 1,300

Endurance (hours) 6 6

Armament: One Lewis machine-gun on a movable mounting for the observer.

Serial Numbers: 9095-9096. (9096 was not built.) N.1070-N.1074: cancelled.

THE Navyplane was a two-seat pusher biplane floatplane sponsored by the Air Department of the Admiralty in 1916, and intended for reconnaissance and bombing duties. It was designed by Harold Bolas of the Air Department in collaboration with Messrs R. J. Mitchell and Richardson of the Supermarine Aviation Works, Ltd., to which company the construction of the machine was entrusted.

Eight weeks after the drawings were received by the Supermarine company the Navyplane was completed, an achievement which brought the manufacturers a letter of appreciation from Commodore Murray F. Sueter. Serial numbers were allotted for seven machines but only one was built. The Navyplane’s test flights were carried out in August, 1916, by Lieutenant-Commander John Seddon.

Structurally the Navyplane was a two-bay biplane with the tail unit supported on four tail-booms, and its most remarkable feature was its monocoque nacelle which, complete with seats and floor-bearers, weighed no more than 80 lb. The nacelle had a sectional glass screen which was led round the nose from the forward windscreen to a point under the pilot’s seat; this gave the crew a good forward and downward view. The Navyplane carried wireless, and the observer had a Lewis gun on a special flexible mounting. The nacelle was mounted mid-way between the wings. The wings themselves were made in three parts and only the outer portions were rigged with dihedral. The tailplane was attached to the upper tail-booms and was of the inverted camber type.

The main floats were pontoon structures and were connected horizontally by only one cross-bar. Each of the twin tail-floats had a water-rudder.

The Navyplane’s original power-plant was a new type of radial engine, the 150 h.p. Smith Static. The design of this engine was brought to England in January, 1915, by an American, John W. Smith, who succeeded in interesting the Admiralty in it almost immediately. The Smith Static was a ten-cylinder single-row radial engine which had offset connecting rods bearing alternately on the cranks of a two-throw crankshaft. The engine must have been reasonably successful. It was tested on the bench and in the air to the satisfaction of the Admiralty. A contract for its production was given to Messrs Heenan & Froude, but only a few were delivered before the Armistice.

The Smith engine was installed quite neatly in the A.D. Navyplane but was later replaced by a 150 h.p. A.R.I. rotary engine. The reason for the change is uncertain, but difficulty may have been experienced with the cooling of the radial. With the A.R.I engine the Navyplane was tested in May, 1917, but with no military load and no observer the performance was very poor.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: The Supermarine Aviation Works Ltd., Woolston, Southampton.

Power: 150 h.p. Smith Static radial engine; later, 150 h.p. A.R.I rotary engine.

Dimensions: Span: 36 ft. Length: 27 ft 9 in. Height: 12 ft 9 in. Chord: 5 ft. Gap: 6 ft 6 in. Stagger: nil. Span of tail: 15 ft 6 in. Airscrew diameter: 8 ft 10 in.

Areas: Wings: 364 sq ft.

Weights (lb) and Performance:

Engine Smith Static A.R.I

Date of Trial Report - 15 May, ’9'7

Weight empty 2,100 2,042

Military load - nil

Crew - 180

Fuel and oil - 328

Weight loaded 3,102 2,550

Maximum speed (m.p.h.) at 2,000 ft 75 64-5

Climb to 2,000 ft - 30 min

Service ceiling (feet) - 1,300

Endurance (hours) 6 6

Armament: One Lewis machine-gun on a movable mounting for the observer.

Serial Numbers: 9095-9096. (9096 was not built.) N.1070-N.1074: cancelled.

Three-quarter Rear View of a "Pusher" Seaplane, built by the Supermarine Co.

A.D. Navyplane No. 9095 with the Smith Static engine.

A.D. Navyplane No. 9095 with the Smith Static engine.

A.D. Flying Boat

THIS two-seat patrol flying boat was designed by the Air Department of the Admiralty. The design work was carried out in the autumn of 1915 under Harris Booth, and the hull was one of the first to be designed by Lieutenant Linton Hope.

Construction of the first hull was undertaken by May, Harden & May, and the completion of the aircraft was entrusted to Pemberton-Billing, Ltd. The detail design was carried out by Harold Bolas, Harold Yendall and Clifford W. Tinson of the Air Department, who went to the Pemberton-Billing works specially for the purpose.

Two prototypes, numbered 1412 and 1413, were flying in 1916. These machines differed slightly in detail: the first had a semi-enclosed bow cockpit, whilst the second had an open bow cockpit and a slightly deeper radiator.

At first, considerable trouble was experienced, for the machine porpoised badly on the water. The Admiralty sought the advice of the scientists who were associated with the experimental work carried out at the Froude National Tank of the National Physical Laboratory. Tests were carried out in August, 1916, at Southampton but were discontinued before the trouble was eradicated. At one time the step was moved two feet farther aft at the suggestion of Squadron Commander J. L. Travers, but that did not cure the machine of porpoising.

A solution must have been found at a later stage, for production was undertaken on a small scale; the production machines were generally similar to No. 1413. The engine for which the original installation was designed was the 150 h.p. Sunbeam Nubian, but both prototypes and production A.D. Flying Boats were built with Hispano-Suiza engines. The standard power-plant was the 200 h.p. geared Hispano-Suiza, but N.1525 at least had the 150 h.p. direct-drive engine of the same make.

The A.D. Flying Boat was flown in February, 1917, by Squadron Commander Travers, Flight-Lieutenant Goodwin and Flight-Lieutenant Barlow, when some excellent performances were recorded. One A.D. Boat rode out a 38 m.p.h. gale for seven hours in an open harbour without damage and shipped only 120 lb of water.

The hull was a wooden monocoque of good form and sturdy construction; it was claimed that the A.D. Flying Boats were stronger, weight for weight, than the larger F boats. One was subjected to rather drastic tests to prove the strength of the hull: it successfully withstood thirty-six successive heavy landings in which it was deliberately stalled at some 10-12 feet above the water. An unusual feature of the design was the provision for the fitting of wheels to enable the machine to be flown from the deck of a carrier vessel; after take-off the wheels were jettisoned.

The upper tailplane was of inverted aerofoil section and was mounted at a slightly negative angle of incidence, for it was thought that in the event of engine failure the reversed camber would prevent the tail from dropping. The lower tailplane, which was awash when the flying boat was taxying in heavy seas, was covered with plywood and was a watertight structure. The wings could be folded, presumably to conserve space when carried on board ship, but contrary to contemporary practice they folded forwards.

One of the later production A.D. Flying Boats, N.1719, was used in experiments with hydrovanes. Two were fitted: one was just aft of the pilot’s cockpit, the other about six feet aft of the trailing edge of the wing. Each hydrovane was some 18 inches below the keel of the hull.

In September, 1918, an A.D. Flying Boat was tested with the 200 h.p. Wolseley Python engine. The installation was experimental, and performance was not good.

The A.D. Flying Boats did not distinguish themselves in any operational way during the war, but with the coming of peace they provided the basis for the successful Supermarine Channel type, which, powered by the 160 h.p. Beardmore or 230 h.p. Siddeley Puma, was one of the earliest commercial flying boats to go into service and was used in many parts of the world.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: Pemberton-Billing, Ltd. (later the Supermarine Aviation Works, Ltd.), Woolston, Southampton.

Power: 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza; 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza; 200 h.p. Wolseley Python.

Dimensions: Span: upper 50 ft 3 15/16 in., lower 39 ft 7 1/4 in. Length: 30 ft 7 in. Height: 13 ft 1 in. Chord: 5 ft 6 in. Gap: 7 ft. Stagger: nil. Dihedral: mainplanes 4°, lower tailplane 2° 30'. Incidence: mainplanes 30, upper tailplane -0° 30', lower tailplane + 5°. Span of tail: upper 9 ft 10 in., lower 8 ft 4 in.

Areas: Wings: 479 sq ft. Tailplanes: total 60 sq ft. Fins and rudders: total 40 sq ft.

Weights (lb) and Performance:

Engine 150 h.p.

Hispano-Suiza 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza 200 h.p. Wolseley Python

No. of Trial Report 8A - N.M.214

Date of Trial Report July 3, 1917 July 12, 1917 September 21, 1918

Type of airscrew used on trial A.D.645 A.B.6622

Weight empty 2,400 2,508 2,360

Military load 216 206 176

Crew 360 360 360

Fuel and oil 351 493 492

Weight loaded 3.327 3,567 3,388

Maximum speed (m.p.h.) at

2,000 ft 91 100 87-5

6,500 ft 83 99 87

10,000 ft - 90 -

m. s. m. s. m. s.

Climb to

2,000 ft 6 00 3 00 5 35

6,500 ft 26 00 14 00 23 50

10,000 ft - - 30 00 55 00

Service ceiling (feet) 7.500 11,000 8,800

Endurance (hours) 5 4 1/2 3 1/2| at 3,000 ft

Armament: One Lewis machine-gun on movable mounting in bow cockpit. A small bomb load could be carried.

Production: Serial numbers indicate that two prototypes and at least twenty-seven production machines were built. On April ist, 1918, when the Air Department handed over to the newly-formed Royal Air Force, eighteen A.D. Flying Boats were in service, nine were under construction or on order, and one had been written off.

Serial Numbers: 1412-1413: ordered under Contract No. C.P. 109611/15. N. 1290-N.1299: ordered under Contract No. A.S.1449. N.1291-N.1299 were not built. N.1520-N.1529: ordered under Contract No. A.S.5388/17. N.1710-N.1719: ordered under Contract No. A.S.20798. N.2450-N.2455: ordered under Contract No. A.S. 18936.

Notes on Individual Machines: N. 1525 had the 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engine. N.1719 was experimentally fitted with hydrovanes below the hull.

Costs:

Airframe, including hull but without engine, instruments and gun £2,853 8s.

Airframe without hull £1,925 0s.

200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engine £1,004 0s.

THIS two-seat patrol flying boat was designed by the Air Department of the Admiralty. The design work was carried out in the autumn of 1915 under Harris Booth, and the hull was one of the first to be designed by Lieutenant Linton Hope.

Construction of the first hull was undertaken by May, Harden & May, and the completion of the aircraft was entrusted to Pemberton-Billing, Ltd. The detail design was carried out by Harold Bolas, Harold Yendall and Clifford W. Tinson of the Air Department, who went to the Pemberton-Billing works specially for the purpose.

Two prototypes, numbered 1412 and 1413, were flying in 1916. These machines differed slightly in detail: the first had a semi-enclosed bow cockpit, whilst the second had an open bow cockpit and a slightly deeper radiator.

At first, considerable trouble was experienced, for the machine porpoised badly on the water. The Admiralty sought the advice of the scientists who were associated with the experimental work carried out at the Froude National Tank of the National Physical Laboratory. Tests were carried out in August, 1916, at Southampton but were discontinued before the trouble was eradicated. At one time the step was moved two feet farther aft at the suggestion of Squadron Commander J. L. Travers, but that did not cure the machine of porpoising.

A solution must have been found at a later stage, for production was undertaken on a small scale; the production machines were generally similar to No. 1413. The engine for which the original installation was designed was the 150 h.p. Sunbeam Nubian, but both prototypes and production A.D. Flying Boats were built with Hispano-Suiza engines. The standard power-plant was the 200 h.p. geared Hispano-Suiza, but N.1525 at least had the 150 h.p. direct-drive engine of the same make.

The A.D. Flying Boat was flown in February, 1917, by Squadron Commander Travers, Flight-Lieutenant Goodwin and Flight-Lieutenant Barlow, when some excellent performances were recorded. One A.D. Boat rode out a 38 m.p.h. gale for seven hours in an open harbour without damage and shipped only 120 lb of water.

The hull was a wooden monocoque of good form and sturdy construction; it was claimed that the A.D. Flying Boats were stronger, weight for weight, than the larger F boats. One was subjected to rather drastic tests to prove the strength of the hull: it successfully withstood thirty-six successive heavy landings in which it was deliberately stalled at some 10-12 feet above the water. An unusual feature of the design was the provision for the fitting of wheels to enable the machine to be flown from the deck of a carrier vessel; after take-off the wheels were jettisoned.

The upper tailplane was of inverted aerofoil section and was mounted at a slightly negative angle of incidence, for it was thought that in the event of engine failure the reversed camber would prevent the tail from dropping. The lower tailplane, which was awash when the flying boat was taxying in heavy seas, was covered with plywood and was a watertight structure. The wings could be folded, presumably to conserve space when carried on board ship, but contrary to contemporary practice they folded forwards.

One of the later production A.D. Flying Boats, N.1719, was used in experiments with hydrovanes. Two were fitted: one was just aft of the pilot’s cockpit, the other about six feet aft of the trailing edge of the wing. Each hydrovane was some 18 inches below the keel of the hull.

In September, 1918, an A.D. Flying Boat was tested with the 200 h.p. Wolseley Python engine. The installation was experimental, and performance was not good.

The A.D. Flying Boats did not distinguish themselves in any operational way during the war, but with the coming of peace they provided the basis for the successful Supermarine Channel type, which, powered by the 160 h.p. Beardmore or 230 h.p. Siddeley Puma, was one of the earliest commercial flying boats to go into service and was used in many parts of the world.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: Pemberton-Billing, Ltd. (later the Supermarine Aviation Works, Ltd.), Woolston, Southampton.

Power: 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza; 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza; 200 h.p. Wolseley Python.

Dimensions: Span: upper 50 ft 3 15/16 in., lower 39 ft 7 1/4 in. Length: 30 ft 7 in. Height: 13 ft 1 in. Chord: 5 ft 6 in. Gap: 7 ft. Stagger: nil. Dihedral: mainplanes 4°, lower tailplane 2° 30'. Incidence: mainplanes 30, upper tailplane -0° 30', lower tailplane + 5°. Span of tail: upper 9 ft 10 in., lower 8 ft 4 in.

Areas: Wings: 479 sq ft. Tailplanes: total 60 sq ft. Fins and rudders: total 40 sq ft.

Weights (lb) and Performance:

Engine 150 h.p.

Hispano-Suiza 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza 200 h.p. Wolseley Python

No. of Trial Report 8A - N.M.214

Date of Trial Report July 3, 1917 July 12, 1917 September 21, 1918

Type of airscrew used on trial A.D.645 A.B.6622

Weight empty 2,400 2,508 2,360

Military load 216 206 176

Crew 360 360 360

Fuel and oil 351 493 492

Weight loaded 3.327 3,567 3,388

Maximum speed (m.p.h.) at

2,000 ft 91 100 87-5

6,500 ft 83 99 87

10,000 ft - 90 -

m. s. m. s. m. s.

Climb to

2,000 ft 6 00 3 00 5 35

6,500 ft 26 00 14 00 23 50

10,000 ft - - 30 00 55 00

Service ceiling (feet) 7.500 11,000 8,800

Endurance (hours) 5 4 1/2 3 1/2| at 3,000 ft

Armament: One Lewis machine-gun on movable mounting in bow cockpit. A small bomb load could be carried.

Production: Serial numbers indicate that two prototypes and at least twenty-seven production machines were built. On April ist, 1918, when the Air Department handed over to the newly-formed Royal Air Force, eighteen A.D. Flying Boats were in service, nine were under construction or on order, and one had been written off.

Serial Numbers: 1412-1413: ordered under Contract No. C.P. 109611/15. N. 1290-N.1299: ordered under Contract No. A.S.1449. N.1291-N.1299 were not built. N.1520-N.1529: ordered under Contract No. A.S.5388/17. N.1710-N.1719: ordered under Contract No. A.S.20798. N.2450-N.2455: ordered under Contract No. A.S. 18936.

Notes on Individual Machines: N. 1525 had the 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engine. N.1719 was experimentally fitted with hydrovanes below the hull.

Costs:

Airframe, including hull but without engine, instruments and gun £2,853 8s.

Airframe without hull £1,925 0s.

200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engine £1,004 0s.

A.D. Flying Boat. Production aircraft with 200 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engine.

Once installed at the Admiralty, Harold Bolas became involved with design of the first A.D. flying-boat, a production version of which is shown here; N1522 of the RNAS.

Once installed at the Admiralty, Harold Bolas became involved with design of the first A.D. flying-boat, a production version of which is shown here; N1522 of the RNAS.

A.D. Flying Boat with 150 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engine.

The A.D. flying boat had a Linton Hope designed hull. Supermarine "built" the type under Contract AS5388/17, (N1520-N1529). N1525 bears Supermarine's logo on the anti-skid fins that were fitted between the interplane struts.

The A.D. flying boat had a Linton Hope designed hull. Supermarine "built" the type under Contract AS5388/17, (N1520-N1529). N1525 bears Supermarine's logo on the anti-skid fins that were fitted between the interplane struts.

Alcock Scout

IN 1917, Flight-Lieutenant J. W. Alcock, who was later to achieve fame for his trans-Atlantic flight with Arthur Whitten Brown in 1919, was serving with No. 2 Wing, R.N.A.S., at Mudros, in the Aegean Sea. While there he made a single-seat fighter biplane, which he called the “Sopwith Mouse”, and which was also known as the Alcock A.1.

This aircraft consisted almost wholly of Sopwith Triplane and Pup components. The fuselage, undercarriage, and most of the lower wing belonged to a Sopwith Triplane, whilst much of the upper wing had originally belonged to a Pup. It appears that a new centre-section was made for the upper wing, and that a centre-section was also fitted to the lower wing. The fuselage appeared to rest on top of the lower main-plane. Two-bay interplane bracing was used, and the interplane struts converged downwards to meet the more closely-spaced spars of the lower wing. The gap was such that the upper wing was brought low above the fuselage, and interfered very little with the pilot’s view.

It is hard to determine how much of the tail unit came from other aircraft, but the rudder might have belonged to a Sopwith type. Triangular fins were fitted, one above and one below the fuselage; and the tail-skid was apparently attached to the rudder-post. The tailplane was mounted centrally on the fuselage.

The Alcock machine was at first fitted with a 100 h.p. Gnome Monosoupape rotary engine, but a 110 h.p. Clerget was later fitted. It is believed that some of the components were taken from the Sopwith Triplane which crashed at Mudros on September 3rd, 1917. Much of the mathematical work involved in the building of the aircraft was done by Commander Constantine of the Greek Navy, who was then in command of the Greek Air Force at Mudros.

Contrary to the official history, Alcock never flew his “Sopwith Mouse”, for it had not been completed when he was taken prisoner by the Turks on the night of September 30th, 1917: he and his crew (Lieutenant S. J. Wise and Lieutenant H. Aird) were captured when No. 2 Wing’s solitary Handley Page O/100 was forced down in the Gulf of Xeros.

But the Alcock Scout was completed and flown. While Alcock was in the civil jail at Seraskerat, Constantinople, he received this message from Wing-Captain F. R. Scarlett, C.B., D.S.O., on October 18th, 1917: “Your baby was taken for an airing, but is still having trouble with teeth. She has now been fitted with new clothing. Now a great improvement in health.” It is believed that the Alcock A.I was first flown on October 15th, 1917.

Early in 1918 the machine was flown over to Stavros by Flight-Lieutenant Starbuck, and it is believed that it was crashed there by that officer.

The foregoing history is based on notes provided by former members of No. 2 Wing, R.N.A.S., who were at Mudros when the Alcock A.I was built; it is very different from the account which appears in Volume V of The War in the Air, the official history. The latter account tells of an aircraft of Alcock’s design fitted with a Benz engine which had been taken from a Friedrichshafen bomber shot down in April, 1917, and goes on to relate how Alcock flew it to attack three enemy seaplanes on September 30th, 1917.

That story is inaccurate, however, for the Alcock A.1 could not have been fitted with a Benz engine, and Alcock was flying a Camel on the occasion in question. It may indicate that he designed an aeroplane round the Benz engine, for it was stated that drawings were sent home from Mudros.

SPECIFICATION

Power: 100 h.p. Gnome Monosoupape; 110 h.p. Clerget.

Armament: Two fixed, forward-firing Vickers machine-guns, synchronised to fire through the airscrew. Service Use: No. 2 Wing, R.N.A.S., Mudros; also flown at Stavros.

IN 1917, Flight-Lieutenant J. W. Alcock, who was later to achieve fame for his trans-Atlantic flight with Arthur Whitten Brown in 1919, was serving with No. 2 Wing, R.N.A.S., at Mudros, in the Aegean Sea. While there he made a single-seat fighter biplane, which he called the “Sopwith Mouse”, and which was also known as the Alcock A.1.

This aircraft consisted almost wholly of Sopwith Triplane and Pup components. The fuselage, undercarriage, and most of the lower wing belonged to a Sopwith Triplane, whilst much of the upper wing had originally belonged to a Pup. It appears that a new centre-section was made for the upper wing, and that a centre-section was also fitted to the lower wing. The fuselage appeared to rest on top of the lower main-plane. Two-bay interplane bracing was used, and the interplane struts converged downwards to meet the more closely-spaced spars of the lower wing. The gap was such that the upper wing was brought low above the fuselage, and interfered very little with the pilot’s view.

It is hard to determine how much of the tail unit came from other aircraft, but the rudder might have belonged to a Sopwith type. Triangular fins were fitted, one above and one below the fuselage; and the tail-skid was apparently attached to the rudder-post. The tailplane was mounted centrally on the fuselage.

The Alcock machine was at first fitted with a 100 h.p. Gnome Monosoupape rotary engine, but a 110 h.p. Clerget was later fitted. It is believed that some of the components were taken from the Sopwith Triplane which crashed at Mudros on September 3rd, 1917. Much of the mathematical work involved in the building of the aircraft was done by Commander Constantine of the Greek Navy, who was then in command of the Greek Air Force at Mudros.

Contrary to the official history, Alcock never flew his “Sopwith Mouse”, for it had not been completed when he was taken prisoner by the Turks on the night of September 30th, 1917: he and his crew (Lieutenant S. J. Wise and Lieutenant H. Aird) were captured when No. 2 Wing’s solitary Handley Page O/100 was forced down in the Gulf of Xeros.

But the Alcock Scout was completed and flown. While Alcock was in the civil jail at Seraskerat, Constantinople, he received this message from Wing-Captain F. R. Scarlett, C.B., D.S.O., on October 18th, 1917: “Your baby was taken for an airing, but is still having trouble with teeth. She has now been fitted with new clothing. Now a great improvement in health.” It is believed that the Alcock A.I was first flown on October 15th, 1917.

Early in 1918 the machine was flown over to Stavros by Flight-Lieutenant Starbuck, and it is believed that it was crashed there by that officer.

The foregoing history is based on notes provided by former members of No. 2 Wing, R.N.A.S., who were at Mudros when the Alcock A.I was built; it is very different from the account which appears in Volume V of The War in the Air, the official history. The latter account tells of an aircraft of Alcock’s design fitted with a Benz engine which had been taken from a Friedrichshafen bomber shot down in April, 1917, and goes on to relate how Alcock flew it to attack three enemy seaplanes on September 30th, 1917.

That story is inaccurate, however, for the Alcock A.1 could not have been fitted with a Benz engine, and Alcock was flying a Camel on the occasion in question. It may indicate that he designed an aeroplane round the Benz engine, for it was stated that drawings were sent home from Mudros.

SPECIFICATION

Power: 100 h.p. Gnome Monosoupape; 110 h.p. Clerget.

Armament: Two fixed, forward-firing Vickers machine-guns, synchronised to fire through the airscrew. Service Use: No. 2 Wing, R.N.A.S., Mudros; also flown at Stavros.

The Ruffy-Baumann School Biplanes

<...>

For elementary training purposes the Ruffy-Baumann company built a two-seat biplane which was in the same class as the D.H.6 and appeared to owe something to that aircraft. The installation of the 70 h.p. Renault engine was very similar to that of the R.A.F. ta in the D.H.6, and the windscreens and gravity fuel tank bore a strong resemblance to the corresponding components on the D.H.6. The Ruffy-Baumann biplane was more refined in general appearance, however, and lacked the primitive angularity of the “Clutching Hand”. The undercarriage embodied skid-like projections, each of which had a small auxiliary wheel at its forward end.

The elementary trainer was later improved by the removal of the skids from the undercarriage and by the addition of a blunt cowling to fair off the nose under the engine bearers. The gravity petrol tank was removed, and a horn-balanced rudder replaced the original plain surface. It was in this form that the machine became known as the Alliance P.1 when the Alliance Aeroplane Co., Ltd., expanded by absorbing a number of small manufacturers of whom the Ruffy, Arnell and Baumann Aviation Co. were one.

<...>

For elementary training purposes the Ruffy-Baumann company built a two-seat biplane which was in the same class as the D.H.6 and appeared to owe something to that aircraft. The installation of the 70 h.p. Renault engine was very similar to that of the R.A.F. ta in the D.H.6, and the windscreens and gravity fuel tank bore a strong resemblance to the corresponding components on the D.H.6. The Ruffy-Baumann biplane was more refined in general appearance, however, and lacked the primitive angularity of the “Clutching Hand”. The undercarriage embodied skid-like projections, each of which had a small auxiliary wheel at its forward end.

The elementary trainer was later improved by the removal of the skids from the undercarriage and by the addition of a blunt cowling to fair off the nose under the engine bearers. The gravity petrol tank was removed, and a horn-balanced rudder replaced the original plain surface. It was in this form that the machine became known as the Alliance P.1 when the Alliance Aeroplane Co., Ltd., expanded by absorbing a number of small manufacturers of whom the Ruffy, Arnell and Baumann Aviation Co. were one.

Ruffy-Baumann Elementary Trainer. This illustration shows the Ruffy-Baumann biplane in its early form with four-wheel main undercarriage.

Ruffy-Baumann Elementary Trainer. The aircraft with simplified undercarriage, cowled engine, and horn-balanced rudder.

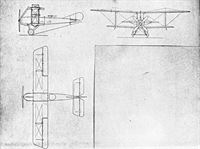

Armstrong Whitworth F.K. 1

THE original aircraft manufacturing firm which bore the name of Armstrong Whitworth came into existence in 1914 as the Aeroplane Department of the large engineering firm of Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd. The first works manager was that great Dutchman, Frederick Koolhoven.

The little single-seat scout which was designated Armstrong Whitworth F.K.1 was not Koolhoven’s first essay in aeroplane design, for he had earlier done much work on several of the Deperdussin monoplanes, but it was his first design for the Armstrong Whitworth company.

The Armstrong Whitworth F.K.1 was a rather frail-looking little biplane which appeared in September, 1914. Even at that early date it showed evidence of having been designed with an eye to production, for its layout was essentially simple. The fuselage was reminiscent of the pre-war Morane-Saulnier monoplanes; so also was the plan-form of the wing-tips. The tail unit betrayed further Morane influence, for there was at first no tailplane but only a balanced elevator. The aircraft had been meant to have the to 80 h.p. Gnome rotary engine, but only a 50 h.p. Gnome could be obtained. There was no alternative but to install the lower-powered engine.

The first flight of the F.K.1 was made by Koolhoven himself. The tail unit was subsequently modified, and a fixed tailplane and plain elevator were fitted. A further modification was the fitting of new, enlarged ailerons which had a pronounced inverse taper.

The F.K.1 was underpowered with only the very nominal 50 h.p. of its Gnome engine, and its performance was no improvement on that of the more powerful contemporary Sopwith, Bristol and Martinsyde Scouts. No development was undertaken.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd., Gosforth, Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Power: 50 h.p. Gnome.

Performance: Maximum speed: 75 m.p.h. Stalling speed: 30 m.p.h.

THE original aircraft manufacturing firm which bore the name of Armstrong Whitworth came into existence in 1914 as the Aeroplane Department of the large engineering firm of Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd. The first works manager was that great Dutchman, Frederick Koolhoven.

The little single-seat scout which was designated Armstrong Whitworth F.K.1 was not Koolhoven’s first essay in aeroplane design, for he had earlier done much work on several of the Deperdussin monoplanes, but it was his first design for the Armstrong Whitworth company.

The Armstrong Whitworth F.K.1 was a rather frail-looking little biplane which appeared in September, 1914. Even at that early date it showed evidence of having been designed with an eye to production, for its layout was essentially simple. The fuselage was reminiscent of the pre-war Morane-Saulnier monoplanes; so also was the plan-form of the wing-tips. The tail unit betrayed further Morane influence, for there was at first no tailplane but only a balanced elevator. The aircraft had been meant to have the to 80 h.p. Gnome rotary engine, but only a 50 h.p. Gnome could be obtained. There was no alternative but to install the lower-powered engine.

The first flight of the F.K.1 was made by Koolhoven himself. The tail unit was subsequently modified, and a fixed tailplane and plain elevator were fitted. A further modification was the fitting of new, enlarged ailerons which had a pronounced inverse taper.

The F.K.1 was underpowered with only the very nominal 50 h.p. of its Gnome engine, and its performance was no improvement on that of the more powerful contemporary Sopwith, Bristol and Martinsyde Scouts. No development was undertaken.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd., Gosforth, Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Power: 50 h.p. Gnome.

Performance: Maximum speed: 75 m.p.h. Stalling speed: 30 m.p.h.

Armstrong Whitworth F.K.3

IN the summer of 1914 it was officially decided to adopt the B.E.2C as a standard type for both the R.F.C. and the R.N.A.S., and among the first manufacturers to be awarded contracts for its production were Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd.

When the necessary drawings were received from the Royal Aircraft Factory, study of them led the firm to declare the B.E.ac to be complicated and difficult to construct. Armstrong Whitworths offered to design and produce an aeroplane which would be structurally simpler than the B.E.2c but equally efficient. The firm were granted permission to do so, and Frederick Koolhoven produced the design of the F.K.3. Work began in August, 1915, and, after the successful completion of official trials, large orders for F.K.3S were placed with Armstrong Whitworth and Messrs Hewlett & Blondeau.

In general appearance the F.K.3 bore a certain resemblance to the B.E.2c, particularly in its original form, when it carried its crew in two separate cockpits similar in shape to those of the B.E., and the pilot occupied the rear seat.

An interesting experimental modification was made to an early F.K.3 in 1915. Koolhoven added a third mainplane above the normal biplane wings in order to measure the increased lift and drag produced by the arrangement. This machine flew well and had a remarkably flat glide. It seems probable that it may have provided some data for the design of the Armstrong Whitworth F.K.12 triplane.

Production F.K.3s showed several major differences from the prototype, chief of which was the interchange of the pilot’s and observer’s seats. The crew occupied one large communal cockpit, somewhat similar to that of the D.H.6. With the pilot in the front seat, the observer could use a gun much more effectively. Dual controls were provided. The shape of the fin and rudder was modified to be neater in appearance but greater in area than that of the prototype; the rudder was still a horn-balanced surface. The undercarriage was an interesting structure which included a central skid and yet had oleo shock absorbers attached to the fuselage, at a time when rubber cord was the almost universal shock absorbing medium. The design of the oleo components was influenced by the recoil mechanism of the famous French 75 mm gun.

The operational service of the F.K.3 was given in the Middle East theatre of war. In Macedonia the type was used by No. 47 Squadron, which arrived at Salonika on September 19th, 1916, and remained in service with that unit until 1918.

Proof of the F.K.3’s sturdiness was provided by an incident which occurred in the course of a combat over Hudova on December 22nd, 1916. The F.K.3 flown by Second Lieutenant W. H. Farrow (observer: Second Lieutenant F. C. Brooks) collided with an enemy machine. The Armstrong Whitworth’s starboard wheel struck the German biplane’s upper wing, and the enemy machine disappeared into the clouds below. Despite a troublesome engine, Farrow landed his F.K.3 safely at Snevce.

The F.K.3 was called upon to perform a variety of duties by No. 47 Squadron. Bombing attacks, such as that made on Hudova on February 1 ith, 1917, when four F.K.3s and a B.E.12 reached the target, were not uncommon. Hudova was bombed frequently, and on such raids the machine was usually flown without an observer, for it was unable to lift both bombs and a second crew-member.

Artillery cooperation and contact patrols were also performed by the hard-working F.K.3s, not without losses, for the enemy did not make the mistake of using only second-class or outmoded machines on the lesser fronts.

At home the F.K.3’s normal use was as a trainer, a duty for which its viceless flying characteristics made it admirably suitable. It was almost as foolproof as the D.H.6, but was much lighter on the controls than either “The Clutching Hand” or the B.E.2C. The F.K.3 was capable of performing all the aerobatics which were in practice at the time of its existence. The type was also used for training observers, when a camera gun was carried. To the R.F.C. it was familiarly known as the “Little Ack”, to distinguish it from the later F.K.8 or “Big Ack”.

After the adoption of the Avro 504 as the standard training aeroplane, the F.K.3 was almost completely supplanted, but a fair number survived until the Armistice. Some, indeed, were sufficiently long-lived to go on the British Civil Register as G-EABY, G-EABZ, G-EAEU and G-EALK. Of these, G-EABY at least was fitted with a plain vee undercarriage.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd., Gosforth, Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Other Contractors: Hewlett & Blondeau, Ltd., Oak Road, Leagrave, Luton.

Power: 90 h.p. R.A.F. Ia; 105 h.p. R.A.F. Ib.

Dimensions: Span: 40 ft 0 5/8 in. Length: 29ft. Height: 11 ft 10 3/4 in. Chord: 5 ft 8 1/4 in. Gap: 5 ft 11 in. Stagger: 1 ft 11 5/8 in. at centre section, 1 ft 11 9/16 in. at outer struts. Dihedral: upper 3° 30', lower 2° 30'. Incidence: 1° 40'. Span of tail: 14 ft 3 in. Airscrew diameter: 9 ft.

Areas: Wings: upper 229 sq ft, lower 213 sq ft, total 442 sq ft. Ailerons: each 16 sq ft, total 64 sq ft. Tailplane: 27 sq ft. Elevators: 22 sq ft. Fin: 5-8 sq ft. Rudder: 9-5 sq ft.

Weights (lb) and Performance:

Engine R.A.F. 1a R.A.F. 1b

No. of Trial Report M.40 M.47

Date of Trial Report May, 1916 June, 1916

Type of airscrew used on trial T.7448 T.7448

Weight empty 1,386 I>375

Military load 80 80

Crew 360 320

Fuel and oil 230 235

Loaded 2,056 2,010

Maximum speed (m.p.h.) at ground level 87 -

1,000 ft 85 -

6,500 ft - 88

8,000 ft 81 -

10,000 ft - 80

m. s. m. s.

Climb to 1,000 ft 3 00 - -

2,000 ft 7 00 - -

3,000 ft 10 30 - -

4,000 ft 14 00 - -

5,000 ft 19 00 - -

6,000 ft 24 00 - -

6,500 ft 26 30 12 00

7,000 ft 29 00 - -

8,000 ft 36 00 - -

9,000 ft 41 00 - -

10,000 ft 48 56 - -

11,000 ft 66 00 - -

12,000 ft 74 00 - -

12,300 ft 78 00 - -

Service ceiling (feet) 12,000 13,000

Endurance at 8,000 (hours) 3 2 1/2

Tankage: Petrol: 28 gallons. Oil: 2-6 gallons.

Armament: One Lewis machine-gun on pillar mounting at the rear of the cockpit. The bomb load, carried in external racks, could include bombs of 16 lb, 100 lb, or 112 lb.

Service Use: Macedonia: No. 47 Squadron, R.F.C. Training: Used at various aerodromes, including No. 31 Training Squadron, Wyton; No. 35 Reserve Squadron, Northolt; Schools of Aerial Gunnery at Hythe and Turnberry; and at Stirling, Dymchurch and Marske. Also used in Egypt.

Production and Allocation: No precise figures for production and original allocations can be given, because the Armstrong Whitworth F.K.3 and F.K.8 were grouped together in the official statistics. Serial numbers indicate that at least 500 F.K.3S were ordered; and it seems obvious that the four Armstrong Whitworths delivered to Training Units in 1915 must have been F.K.3s, as also would be most of the eighty delivered in 1916. On October 31st, 1918, the Royal Air Force had sixty-two F.K.3s on charge: fifty-one were at schools and home aerodromes, six were in Egypt, three in Palestine, one was at an Aeroplane Repair Depot and one at an experimental unit.

Serial Numbers: 5328-5334, 5614 and 6186-6227 were ordered from Armstrong Whitworth under Contract No. 94/A/103. 5504-5553. A.1461-A.1510, A.8091-A.8140 and B.9501-B.9800 were ordered from Hewlett & Blondeau.

Notes on Individual Machines: A.1484: used by No. 35 Reserve Squadron. B.9518: became G-EABZ. B.9594: used at Marske. B.9603: became G-EALK. B.9612: became G-EAEU. B.9629: became G-EABY.

Costs:

Airframe without engine, instruments and gun £1,127 10s.

R.A.F. 1a engine £522 10s.

IN the summer of 1914 it was officially decided to adopt the B.E.2C as a standard type for both the R.F.C. and the R.N.A.S., and among the first manufacturers to be awarded contracts for its production were Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd.

When the necessary drawings were received from the Royal Aircraft Factory, study of them led the firm to declare the B.E.ac to be complicated and difficult to construct. Armstrong Whitworths offered to design and produce an aeroplane which would be structurally simpler than the B.E.2c but equally efficient. The firm were granted permission to do so, and Frederick Koolhoven produced the design of the F.K.3. Work began in August, 1915, and, after the successful completion of official trials, large orders for F.K.3S were placed with Armstrong Whitworth and Messrs Hewlett & Blondeau.

In general appearance the F.K.3 bore a certain resemblance to the B.E.2c, particularly in its original form, when it carried its crew in two separate cockpits similar in shape to those of the B.E., and the pilot occupied the rear seat.

An interesting experimental modification was made to an early F.K.3 in 1915. Koolhoven added a third mainplane above the normal biplane wings in order to measure the increased lift and drag produced by the arrangement. This machine flew well and had a remarkably flat glide. It seems probable that it may have provided some data for the design of the Armstrong Whitworth F.K.12 triplane.

Production F.K.3s showed several major differences from the prototype, chief of which was the interchange of the pilot’s and observer’s seats. The crew occupied one large communal cockpit, somewhat similar to that of the D.H.6. With the pilot in the front seat, the observer could use a gun much more effectively. Dual controls were provided. The shape of the fin and rudder was modified to be neater in appearance but greater in area than that of the prototype; the rudder was still a horn-balanced surface. The undercarriage was an interesting structure which included a central skid and yet had oleo shock absorbers attached to the fuselage, at a time when rubber cord was the almost universal shock absorbing medium. The design of the oleo components was influenced by the recoil mechanism of the famous French 75 mm gun.

The operational service of the F.K.3 was given in the Middle East theatre of war. In Macedonia the type was used by No. 47 Squadron, which arrived at Salonika on September 19th, 1916, and remained in service with that unit until 1918.

Proof of the F.K.3’s sturdiness was provided by an incident which occurred in the course of a combat over Hudova on December 22nd, 1916. The F.K.3 flown by Second Lieutenant W. H. Farrow (observer: Second Lieutenant F. C. Brooks) collided with an enemy machine. The Armstrong Whitworth’s starboard wheel struck the German biplane’s upper wing, and the enemy machine disappeared into the clouds below. Despite a troublesome engine, Farrow landed his F.K.3 safely at Snevce.

The F.K.3 was called upon to perform a variety of duties by No. 47 Squadron. Bombing attacks, such as that made on Hudova on February 1 ith, 1917, when four F.K.3s and a B.E.12 reached the target, were not uncommon. Hudova was bombed frequently, and on such raids the machine was usually flown without an observer, for it was unable to lift both bombs and a second crew-member.

Artillery cooperation and contact patrols were also performed by the hard-working F.K.3s, not without losses, for the enemy did not make the mistake of using only second-class or outmoded machines on the lesser fronts.

At home the F.K.3’s normal use was as a trainer, a duty for which its viceless flying characteristics made it admirably suitable. It was almost as foolproof as the D.H.6, but was much lighter on the controls than either “The Clutching Hand” or the B.E.2C. The F.K.3 was capable of performing all the aerobatics which were in practice at the time of its existence. The type was also used for training observers, when a camera gun was carried. To the R.F.C. it was familiarly known as the “Little Ack”, to distinguish it from the later F.K.8 or “Big Ack”.

After the adoption of the Avro 504 as the standard training aeroplane, the F.K.3 was almost completely supplanted, but a fair number survived until the Armistice. Some, indeed, were sufficiently long-lived to go on the British Civil Register as G-EABY, G-EABZ, G-EAEU and G-EALK. Of these, G-EABY at least was fitted with a plain vee undercarriage.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd., Gosforth, Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Other Contractors: Hewlett & Blondeau, Ltd., Oak Road, Leagrave, Luton.

Power: 90 h.p. R.A.F. Ia; 105 h.p. R.A.F. Ib.

Dimensions: Span: 40 ft 0 5/8 in. Length: 29ft. Height: 11 ft 10 3/4 in. Chord: 5 ft 8 1/4 in. Gap: 5 ft 11 in. Stagger: 1 ft 11 5/8 in. at centre section, 1 ft 11 9/16 in. at outer struts. Dihedral: upper 3° 30', lower 2° 30'. Incidence: 1° 40'. Span of tail: 14 ft 3 in. Airscrew diameter: 9 ft.

Areas: Wings: upper 229 sq ft, lower 213 sq ft, total 442 sq ft. Ailerons: each 16 sq ft, total 64 sq ft. Tailplane: 27 sq ft. Elevators: 22 sq ft. Fin: 5-8 sq ft. Rudder: 9-5 sq ft.

Weights (lb) and Performance:

Engine R.A.F. 1a R.A.F. 1b

No. of Trial Report M.40 M.47

Date of Trial Report May, 1916 June, 1916

Type of airscrew used on trial T.7448 T.7448

Weight empty 1,386 I>375

Military load 80 80

Crew 360 320

Fuel and oil 230 235

Loaded 2,056 2,010

Maximum speed (m.p.h.) at ground level 87 -

1,000 ft 85 -

6,500 ft - 88

8,000 ft 81 -

10,000 ft - 80

m. s. m. s.

Climb to 1,000 ft 3 00 - -

2,000 ft 7 00 - -

3,000 ft 10 30 - -

4,000 ft 14 00 - -

5,000 ft 19 00 - -

6,000 ft 24 00 - -

6,500 ft 26 30 12 00

7,000 ft 29 00 - -

8,000 ft 36 00 - -

9,000 ft 41 00 - -

10,000 ft 48 56 - -

11,000 ft 66 00 - -

12,000 ft 74 00 - -

12,300 ft 78 00 - -

Service ceiling (feet) 12,000 13,000

Endurance at 8,000 (hours) 3 2 1/2

Tankage: Petrol: 28 gallons. Oil: 2-6 gallons.

Armament: One Lewis machine-gun on pillar mounting at the rear of the cockpit. The bomb load, carried in external racks, could include bombs of 16 lb, 100 lb, or 112 lb.

Service Use: Macedonia: No. 47 Squadron, R.F.C. Training: Used at various aerodromes, including No. 31 Training Squadron, Wyton; No. 35 Reserve Squadron, Northolt; Schools of Aerial Gunnery at Hythe and Turnberry; and at Stirling, Dymchurch and Marske. Also used in Egypt.

Production and Allocation: No precise figures for production and original allocations can be given, because the Armstrong Whitworth F.K.3 and F.K.8 were grouped together in the official statistics. Serial numbers indicate that at least 500 F.K.3S were ordered; and it seems obvious that the four Armstrong Whitworths delivered to Training Units in 1915 must have been F.K.3s, as also would be most of the eighty delivered in 1916. On October 31st, 1918, the Royal Air Force had sixty-two F.K.3s on charge: fifty-one were at schools and home aerodromes, six were in Egypt, three in Palestine, one was at an Aeroplane Repair Depot and one at an experimental unit.

Serial Numbers: 5328-5334, 5614 and 6186-6227 were ordered from Armstrong Whitworth under Contract No. 94/A/103. 5504-5553. A.1461-A.1510, A.8091-A.8140 and B.9501-B.9800 were ordered from Hewlett & Blondeau.

Notes on Individual Machines: A.1484: used by No. 35 Reserve Squadron. B.9518: became G-EABZ. B.9594: used at Marske. B.9603: became G-EALK. B.9612: became G-EAEU. B.9629: became G-EABY.

Costs:

Airframe without engine, instruments and gun £1,127 10s.

R.A.F. 1a engine £522 10s.

Одна из ранних серийных машин.

One of the first seven F.K.3 aircraft, a batch ordered in April 1915.

Armstrong Whitworth F.K.3 in original form with pilot in rear, separate cockpits, and small fin and rudder.

One of the first seven F.K.3 aircraft, a batch ordered in April 1915.

Armstrong Whitworth F.K.3 in original form with pilot in rear, separate cockpits, and small fin and rudder.

Armstrong Whitworth F.K.12

THAT excellent aero-engine, the 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce which was later named Eagle, was originally designed and developed as a power unit for seaplanes. About the end of January, 1916, the Admiralty transferred a few of these engines to the War Office for experimental purposes; and the aircraft manufacturers of the day were invited to submit designs for multi-seat escort fighters embodying the Rolls-Royce engine. No doubt it was hoped to produce an aeroplane capable of defeating the Fokker monoplane, which was then coming into menacing prominence.

Several firms submitted designs to meet the specification, which demanded a maximum endurance of seven hours to enable the machine to be used for anti-Zeppelin work if need be; but only Armstrong Whitworth, Sopwith and Vickers were awarded contracts for the construction of prototypes. All three designs were highly unorthodox, and all provided accommodation for their gunners in unusual positions.

The Armstrong Whitworth design was the F.K.12, a big triplane which appeared in two different forms. The version which apparently came first was probably the most remarkable British aeroplane of the 1914-18 war. Its central mainplane was of much greater span than the top and bottom wings, and on it the fuselage was mounted almost symmetrically. There was virtually no forward-reaching nose on the fuselage; the airscrew revolved just in front of the leading edge of the central wing.

The undercarriage consisted of a central unit carrying two main wheels on a sprung leg, and a small sprung wheel under each wing tip. A long pylon just behind the trailing edge of the bottom wing was fitted with a skid which kept the tail of the fuselage clear of the ground.

The central mainplane carried two nacelles for gunners, each of whom apparently was to have had a Lewis gun on a rocking-post mounting. The gunners were in front of the tractor airscrew and had a fine field of fire in all forward directions.

The second F.K.12 had a similar wing configuration, but was a much more cumbersome machine. The wing span and area were increased, and the wings had two bays of interplane bracing. The fuselage was more conventional in appearance, but was deeper and filled the gap between middle and bottom mainplanes. The long nose must have interfered with the gunners’ view. The wing-mounted nacelles were retained, but were of different form and were underslung from the centre wing. The undercarriage consisted of two twin-wheel units under the fuselage. Serial numbers were allotted for four prototypes, but it is doubtful whether all were built.

The Armstrong Whitworth F.K.12 was tested by Peter Legh, but its performance fell short of expectations. Furthermore, in common with the Sopwith and Vickers types, it appeared at about the same time as an effective British interrupter gear for machine-guns. Development was abandoned in favour of more conventional designs which could be effectively armed.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd., Gosforth, Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Power: 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce.

Armament: Two Lewis machine-guns, one on a rocking-post mounting in each outboard nacelle.

Serial Numbers: 7838-7841.

THAT excellent aero-engine, the 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce which was later named Eagle, was originally designed and developed as a power unit for seaplanes. About the end of January, 1916, the Admiralty transferred a few of these engines to the War Office for experimental purposes; and the aircraft manufacturers of the day were invited to submit designs for multi-seat escort fighters embodying the Rolls-Royce engine. No doubt it was hoped to produce an aeroplane capable of defeating the Fokker monoplane, which was then coming into menacing prominence.

Several firms submitted designs to meet the specification, which demanded a maximum endurance of seven hours to enable the machine to be used for anti-Zeppelin work if need be; but only Armstrong Whitworth, Sopwith and Vickers were awarded contracts for the construction of prototypes. All three designs were highly unorthodox, and all provided accommodation for their gunners in unusual positions.

The Armstrong Whitworth design was the F.K.12, a big triplane which appeared in two different forms. The version which apparently came first was probably the most remarkable British aeroplane of the 1914-18 war. Its central mainplane was of much greater span than the top and bottom wings, and on it the fuselage was mounted almost symmetrically. There was virtually no forward-reaching nose on the fuselage; the airscrew revolved just in front of the leading edge of the central wing.

The undercarriage consisted of a central unit carrying two main wheels on a sprung leg, and a small sprung wheel under each wing tip. A long pylon just behind the trailing edge of the bottom wing was fitted with a skid which kept the tail of the fuselage clear of the ground.

The central mainplane carried two nacelles for gunners, each of whom apparently was to have had a Lewis gun on a rocking-post mounting. The gunners were in front of the tractor airscrew and had a fine field of fire in all forward directions.

The second F.K.12 had a similar wing configuration, but was a much more cumbersome machine. The wing span and area were increased, and the wings had two bays of interplane bracing. The fuselage was more conventional in appearance, but was deeper and filled the gap between middle and bottom mainplanes. The long nose must have interfered with the gunners’ view. The wing-mounted nacelles were retained, but were of different form and were underslung from the centre wing. The undercarriage consisted of two twin-wheel units under the fuselage. Serial numbers were allotted for four prototypes, but it is doubtful whether all were built.

The Armstrong Whitworth F.K.12 was tested by Peter Legh, but its performance fell short of expectations. Furthermore, in common with the Sopwith and Vickers types, it appeared at about the same time as an effective British interrupter gear for machine-guns. Development was abandoned in favour of more conventional designs which could be effectively armed.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd., Gosforth, Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Power: 250 h.p. Rolls-Royce.

Armament: Two Lewis machine-guns, one on a rocking-post mounting in each outboard nacelle.

Serial Numbers: 7838-7841.

The first version of the Armstrong Whitworth triplane, probably known as the F.K.5. It is believed that this aircraft never flew.

The Armstrong Whitworth F.K.12 in its first form.

The Armstrong Whitworth F.K.12 in its first form.

Armstrong Whitworth F.K. 10

IT has been said, not without some truth, that almost every variation of the aeroplane form of aircraft was tried out during the 1914-18 war by one or other of the combatants. Monoplanes, biplanes and triplanes appeared in astonishing variety and profusion, and the quadruplane form was built and flown in Britain and Germany.

In Britain, at least four quadruplane types were built. The Supermarine concern built two large twin-engined quadruplanes, the P.B.29 of 1915 and the Night Hawk of 1916; the little Wight quadruplane single-seat fighter appeared in three slightly different forms; and the two-seat fighter-reconnaissance type was represented by the Armstrong Whitworth F.K.10. On the German side, at least two single-seat fighter quadruplanes were built; namely the Naglo with the 160 h.p. Benz, and the Euler with an Oberursel rotary engine.

The Armstrong Whitworth F.K.10 provided an excellent example of the striking originality of thought possessed by Frederick Koolhoven. The prototype had a slender fuselage, a fixed tailplane, and an ugly horn-balanced rudder; the engine was the 110 h.p. Clerget. It is doubtful whether any military equipment was fitted to this machine, and it seems probable that it may have been built solely to test the quadruplane wing arrangement.

The later prototypes had the same wing arrangement as the first, but the fuselage was more portly and the tail unit had been re-designed. There was now no fixed tailplane but only a balanced elevator reminiscent of the Morane-Saulnier monoplanes, and the vertical tail surfaces were of more pleasing form with approximately equal areas of fin above and below the fuselage. The 130 h.p. Clerget replaced the 110 h.p. engine of the first machine, but at least one F.K.10 had a 110 h.p. Le Rhone.

The pilot, from his cockpit ahead of the wings, had a remarkably good view in almost all forward and upward directions. This was one of the principal reasons for the adoption of the quadruplane layout, and good manoeuvrability was probably hoped for as a result of the use of four ailerons on each side and the compression of the wing area into a short span.

Armament was fitted to these F.K.10s, and consisted of a fixed synchronised Vickers gun for the pilot and a stripped Lewis on a rocking-post mounting for the observer.

A small batch of F.K.10s were ordered for the R.F.C. from Angus Sanderson & Co., presumably owing to Armstrong Whitworth’s pre-occupation with production of the F.K.8.

The R.N.A.S. were also interested in the type and ordered a few from other contractors. Two machines, N.511 and N.512, were built by the Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co., Ltd., in 1917. The first was intended to be a two-seat fighter, for which purpose a Scarff ring-mounting was provided for the observer’s Lewis gun; the second machine, N.512, was built as a bomber. N.511 underwent its trials at Boroughbridge on April 26th, 1917.

The Phoenix-built F.K.10s differed in detail from the machines built by Armstrong Whitworth. They had horse-shoe cowlings instead of full circular; the coaming in front of the pilot’s cockpit was fuller and no windscreen was fitted; and small end-plates were fitted at the inboard ends of the bottom mainplanes.

All the F.K.10s were characterised by the heavily staggered wings connected by a single “plank” interplane strut and similar centre section struts, and by the peculiar single-strut undercarriage braced in three planes by cross-wires. The resulting structure did not look particularly strong, but presumably it worked well enough.

The R.F.C. flew an F.K.10 at Gosport, and the R.N.A.S. quadruplanes were flown at Manston; but the F.K.10 was not a good aeroplane, and production was not undertaken. The machine must have been sensitive on the elevators in the same way as the Moranes were, and it suffered from a form of wing flutter. The type was ultimately abandoned and four F.K.10s were scrapped at Manston in 1917.

A remarkable development was projected as the F.K.11. It was to consist of the fuselage of an F.K.10 fitted with fifteen narrow-chord mainplanes, heavily staggered and mounted close together.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd., Gosforth, Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Other Contractors: The Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Bradford; Angus Sanderson & Co., Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Power: 110 h.p. Clerget; 130 h.p. Clerget; 110 h.p. Le Rhone.

Dimensions: Span: 27 ft 10 in. Length: 22 ft 3 in. Height: 11 ft 6 in. Chord: 3 ft 7 in. Gap: 2 ft 8 in. Stagger: 1 ft 5 in. Dihedral: 1° 30'. Incidence: 3°.

Areas: Wings: top 102-6 sq ft, second 92-6 sq ft, third 92-6 sq ft, bottom 102-6 sq ft; total 390-4 sq ft. Ailerons: each 8-4 sq ft, total 67-2 sq ft. Elevators: 16 sq ft. Fin: 1-9 sq ft. Rudder: 8 sq ft.

Weights (lb) and Performance:

Engine 110 h.p. Clerget 130 h.p. Clerget Manufacturer’s figures for 130 h.p.

No. of Trial Report M.77 M.82 -

Date of Trial Report Dec. 1916 Mar., 1917 -

Type of airscrew used on trial L.P.710C L.P.710C -

Weight empty 1,226 1,236 1,143

Military load 160 160 -

Crew 360 360 -

Fuel and oil 292 263 -

Weight loaded 2,038 2,019 1,804

Maximum speed (m.p.h.)

at ground level - - 105

6,500 ft 94 84 -

10,000 ft 87-5 74 99

m. s. m. s. m. s.

Climb to

6,500 ft 14 20 15 50 - -

10,000 ft 23 35 37 10 17 00

Service ceiling (feet) 13,000 10,000 -

Endurance (hours) 3 2 1/2 -

Armament: One fixed forward-firing Vickers machine-gun mounted centrally above the engine cowling and synchronised to fire through the airscrew; one Lewis machine-gun on rocking-post mounting or Scarff ring-mounting in rear cockpit.

Service Use: Flown by the R.F.C. at Gosport and by the R.N.A.S. at Manston.

Production and Allocation: Serial numbers were allotted for at least eleven Armstrong Whitworth F.K.10s, but all may not have been completed. One was delivered to the R.F.C. Training Unit at Gosport in 1916.

Serial Numbers: A.5212-A.5214: built by Armstrong Whitworth under Contract No. 87/A/1254. B.3996-B.4000: built by Angus Sanderson. N.511-N.512: built by Phoenix Dynamo Mfg. Co. under Contract No. C.P.135178/16. N.514: built under Contract No. C.P.100565/16.

IT has been said, not without some truth, that almost every variation of the aeroplane form of aircraft was tried out during the 1914-18 war by one or other of the combatants. Monoplanes, biplanes and triplanes appeared in astonishing variety and profusion, and the quadruplane form was built and flown in Britain and Germany.

In Britain, at least four quadruplane types were built. The Supermarine concern built two large twin-engined quadruplanes, the P.B.29 of 1915 and the Night Hawk of 1916; the little Wight quadruplane single-seat fighter appeared in three slightly different forms; and the two-seat fighter-reconnaissance type was represented by the Armstrong Whitworth F.K.10. On the German side, at least two single-seat fighter quadruplanes were built; namely the Naglo with the 160 h.p. Benz, and the Euler with an Oberursel rotary engine.

The Armstrong Whitworth F.K.10 provided an excellent example of the striking originality of thought possessed by Frederick Koolhoven. The prototype had a slender fuselage, a fixed tailplane, and an ugly horn-balanced rudder; the engine was the 110 h.p. Clerget. It is doubtful whether any military equipment was fitted to this machine, and it seems probable that it may have been built solely to test the quadruplane wing arrangement.

The later prototypes had the same wing arrangement as the first, but the fuselage was more portly and the tail unit had been re-designed. There was now no fixed tailplane but only a balanced elevator reminiscent of the Morane-Saulnier monoplanes, and the vertical tail surfaces were of more pleasing form with approximately equal areas of fin above and below the fuselage. The 130 h.p. Clerget replaced the 110 h.p. engine of the first machine, but at least one F.K.10 had a 110 h.p. Le Rhone.

The pilot, from his cockpit ahead of the wings, had a remarkably good view in almost all forward and upward directions. This was one of the principal reasons for the adoption of the quadruplane layout, and good manoeuvrability was probably hoped for as a result of the use of four ailerons on each side and the compression of the wing area into a short span.

Armament was fitted to these F.K.10s, and consisted of a fixed synchronised Vickers gun for the pilot and a stripped Lewis on a rocking-post mounting for the observer.

A small batch of F.K.10s were ordered for the R.F.C. from Angus Sanderson & Co., presumably owing to Armstrong Whitworth’s pre-occupation with production of the F.K.8.

The R.N.A.S. were also interested in the type and ordered a few from other contractors. Two machines, N.511 and N.512, were built by the Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co., Ltd., in 1917. The first was intended to be a two-seat fighter, for which purpose a Scarff ring-mounting was provided for the observer’s Lewis gun; the second machine, N.512, was built as a bomber. N.511 underwent its trials at Boroughbridge on April 26th, 1917.

The Phoenix-built F.K.10s differed in detail from the machines built by Armstrong Whitworth. They had horse-shoe cowlings instead of full circular; the coaming in front of the pilot’s cockpit was fuller and no windscreen was fitted; and small end-plates were fitted at the inboard ends of the bottom mainplanes.

All the F.K.10s were characterised by the heavily staggered wings connected by a single “plank” interplane strut and similar centre section struts, and by the peculiar single-strut undercarriage braced in three planes by cross-wires. The resulting structure did not look particularly strong, but presumably it worked well enough.

The R.F.C. flew an F.K.10 at Gosport, and the R.N.A.S. quadruplanes were flown at Manston; but the F.K.10 was not a good aeroplane, and production was not undertaken. The machine must have been sensitive on the elevators in the same way as the Moranes were, and it suffered from a form of wing flutter. The type was ultimately abandoned and four F.K.10s were scrapped at Manston in 1917.

A remarkable development was projected as the F.K.11. It was to consist of the fuselage of an F.K.10 fitted with fifteen narrow-chord mainplanes, heavily staggered and mounted close together.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., Ltd., Gosforth, Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Other Contractors: The Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Bradford; Angus Sanderson & Co., Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Power: 110 h.p. Clerget; 130 h.p. Clerget; 110 h.p. Le Rhone.

Dimensions: Span: 27 ft 10 in. Length: 22 ft 3 in. Height: 11 ft 6 in. Chord: 3 ft 7 in. Gap: 2 ft 8 in. Stagger: 1 ft 5 in. Dihedral: 1° 30'. Incidence: 3°.

Areas: Wings: top 102-6 sq ft, second 92-6 sq ft, third 92-6 sq ft, bottom 102-6 sq ft; total 390-4 sq ft. Ailerons: each 8-4 sq ft, total 67-2 sq ft. Elevators: 16 sq ft. Fin: 1-9 sq ft. Rudder: 8 sq ft.

Weights (lb) and Performance:

Engine 110 h.p. Clerget 130 h.p. Clerget Manufacturer’s figures for 130 h.p.

No. of Trial Report M.77 M.82 -

Date of Trial Report Dec. 1916 Mar., 1917 -