M.Goodall, A.Tagg British Aircraft before the Great War (Schiffer)

Deleted by request of (c)Schiffer Publishing

SOPWITH Tractor hydro-biplane Type ADH

A batch of three of these machines with 90hp Austro-Daimler engines was authorized in advance of contract, on 20 May 1913. The type was not built but was presumably of similar basic design to the Type D, since the cost of work carried out was transferred over to a later War Office contract for more of this latter type on 8 August 1913.

SOPWITH Tractor hydro-biplane Type DM

Sopwith instructed the works on 2 June 1913 to proceed with the manufacture of a twin float seaplane to compete for the .5,000 prize offered by The Daily Mail, for the Seaplane Circuit of Britain, to commence from Southampton Water on 16 August 1913. In the event the Sopwith machine was the only competitor to reach the starting line. However after flying the 240 miles to Yarmouth, accompanied by Kauper, Hawker was forced to give up due to sickness, caused by fumes from a broken exhaust, and sunstroke. A second attempt was made on 25 August 1913, in which they crash landed in the sea near Dublin, after covering 1,043 miles. On the way they suffered a broken oil pipe, and Kauper broke his arm in the crash. Hawker was awarded . 1,000 by The Daily Mail, in recognition of a remarkable flight.

The aircraft was recovered and rebuilt with an extra fuel tank, to compete in the Michelin Contest later that year. However the machine did not compete, and in February 1914 the Admiralty purchased the aircraft for .1,275 under Contract CP31415/14X2430, for use as both a seaplane and landplane. As serial No.151 it was delivered to Calshot in April, but was soon damaged in a forced landing and was deleted on 19 August 1914. The Navy considered the machine quite unsuitable for observation purposes due, no doubt, to the restricted view from the front cockpit.

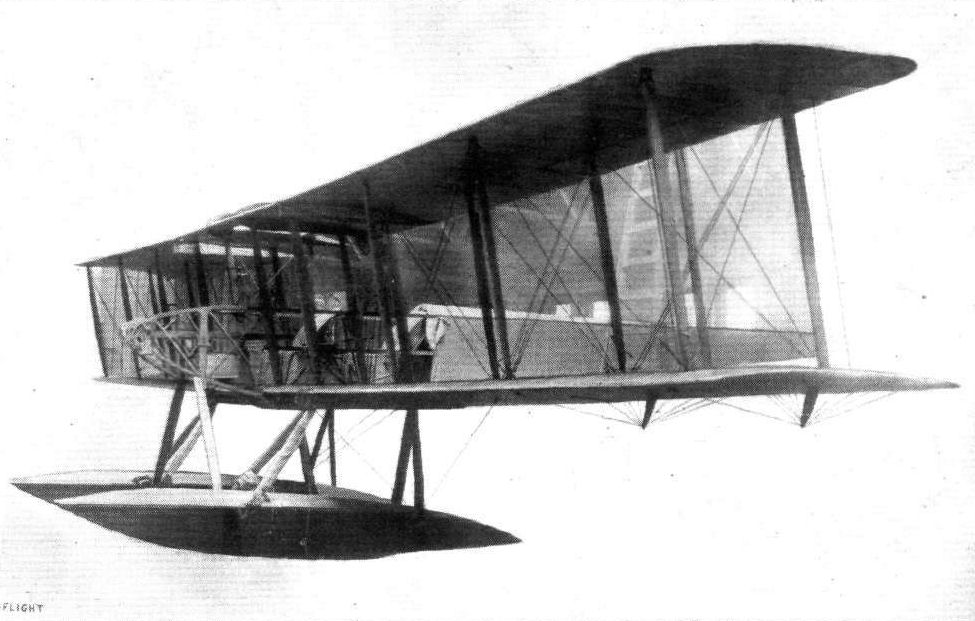

The machine was a conventional biplane, with wings of three-and-a-half bays, the smaller bays adjacent to the fuselage. The single step floats were attached at the first interplane struts, and were stabilized by struts to the engine mounting and by cables, the small streamlined tail float was replaced by one of box type, of greater volume.

The control surfaces were conventional with a balanced rudder, but no fin, and there were ailerons on all four wings. The top wing center section was cut away for ease of exit by the crew, and the inboard ends of the wings were fitted with end plates. Radiators were mounted on either side of the fuselage, alongside the front passenger's cockpit.

Power: 100hp Green six-cylinder inline water-cooled driving a 8ft 6in diameter Chauviere propeller.

Data

Span 49ft 6in (50ft.)*

Chord 5ft3/4in (5ft ll/2in)*

Gap 5ft4 1/2in

Area 500 sq. ft

Area tailplane 120 sq. ft

Area elevators 26 sq. ft

Area rudder 12 sq. ft

Length 31ft (31ft 6in)*

Floats 10ft long by 2ft beam

(14ft long by 2ft 4 1/2 in beam)*

Weight 1,600lb.

Weight allup 2,400 lb.

Speed 60-65 mph

*Data from Flight alternatives from The Aeroplane

SOPWITH tractor seaplanes Admiralty Types 137 and 138

A Contract CP30775/14X2387 initiated instructions to the works on 11 February 1914 to proceed with the manufacture of two seaplanes of similar type, but with quite different engines, and these became serial Nos. 137 and 138 in service with the Navy. The machines were built at Kingston with final assembly of 137 at Woolston and 138 at Calshot. The two aircraft were recorded 'ex works' on the 15th and 5th of August respectively, and were handed over to the Navy at Calshot a few days later, being accepted on the 21st and 12th of August. The total cost was ?2,269 for No. 137 and ?2,633 for No. 138.

In service the machines suffered the usual periods of unserviceability, particularly 137, which was crashed badly on 3 September 1914. No.138 was used for torpedo carrying trials in August and September and made several successful drops. Both aircraft remained in the Solent area and both were deleted on 1 January 1916.

The two machines were of the same basic design, with changes associated with the use of different engines. The wings were of unequal span, with struts bracing the overhanging top portions and ailerons on all four wings. The wings of No. 137 were of two bay type, but No. 138 required more wing area, the increased span being provided by the insertion of a smaller inner bay.

The fuselage was a wooden braced girder with the pilot seated in the rear cockpit. A conventional tail unit of fin, rudder, tailplane and divided elevators was fitted. The machine was mounted on a chassis of struts in the form of an inverted-W with crossbars. The twin single step floats were sprung by leaf springs, at the rear attachments only. A tail float was carried on struts well below the rear fuselage, and was fitted with a water rudder.

A Sopwith drawing No. 197, dated 20 January 1914, exists of the Salmson-engined version and drawing No.213, dated 8 January 1914, of the Austro-Daimler version, both signed by Ashfield and these show various features which were later changed on the actual aircraft. These changes included the reduction of stagger to overcome tail heaviness on No. 138, and the use of a larger tailplane of rectangular form, rather than one with a semicircular leading edge. This latter change appears also on No. 137, as did the incorporation of ailerons on all four wings. The original position of the radiators on No. 138 had been higher, with their tops being just below the top wing. On No. 137 the original water tank under the top center section was retained, but the flank radiators were replaced by one at the nose just behind the propeller.

Power:

No.137 120hp Austro-Daimler six-cylinder inline water-cooled later changed in service to that as fitted in No.138.

No.138 200hp Salmson 2M7 (Canton-Unne) fourteen-cylinder two-row water-cooled radial. Initially fitted with a two-bladed Lang propeller later changed to one with four blades.

Data (From Sopwith drawings Nos. 197 and 213)

No.137

Span top 48ft

Span bottom 36ft

Chord 6ft 9in (7ft 6in over top ailerons)

Gap 6ft

Stagger 1ft 3in

Dihedral 1 1/4 deg.

Area 517 sq. ft

Length 33ft 2in

Height 12ft 3in

Weight 1,980lb.

Weight allup 2,650 lb. with 5hr of fuel

Area tailplane 36.68 sq. ft

Area elevators 26.40 sq. ft

Area fin 5.20 sq. ft

Area rudder 10 sq. ft

Top ailerons 28 sq. ft each (inc. in wing area)

Span tailplane 10ft 4in

Span elevators 12ft

Main floats spaced at 10ft centres

15ft long 2ft 4in beam 2ft 1in deep

No.138 Span top 56ft

Span bottom 48ft

Chord 6ft 9in (7ft 6in over top ailerons)

Gap 6ft 3in

Area 658 sq. ft

Length 34ft 10in

Height 12ft 8in

Weight 2,190lb.

Weight allup 3,450 lb.

Area tailplane 36.68 sq. ft

Area elevators 26.40sq ft

Area fin 5.20 sq. ft

Area rudder 10 sq. ft

Top ailerons 30 sq. ft each (inc. in wing area)

Span tailplane 10ft 4in

Span elevators 12ft

Main floats spaced at 10ft centers

16ft long 2ft 9in beam 2ft 1in deep

H.King Sopwith Aircraft 1912-1920 (Putnam)

Circuit Seaplanes

Before identifying and describing the two distinct Sopwith types to which this chapter is devoted it will be helpful to outline the circumstances that led to their construction.

As early as May 1910 that most air-minded of newspapers the Daily Mail (with an eye as closely fixed on circulation as on circuit-flying) had offered ?10,000 to the winner of a 1,010-mile 'Circuit of Britain' contest, specifying thirteen compulsory control stops and five days for completion of the flight. The contest did not, in the event, take place until July 1911, when thirty aircraft were entered. Among these no Sopwith was numbered, and as things transpired the Cody biplane was the only British aircraft to stay the course - and this machine came fourth. (Sopwith was a great admirer of Cody, as were so many of his contemporaries).

In March 1913 the same newspaper offered ?5.000 to the winner of another Circuit of Britain, the main conditions being that the aircraft must be a 'waterplane' entirely of British design and construction, and that, starting and finishing from the mouth of the Thames (as befitted an 'all-British' event), the machine should fly - in 72 continuous hours not only round England, Scotland and Wales, but to within one mile of Kingstown Harbour, Ireland. At the same time a second Daily Mail prize, off 10,000, was offered to the first pilot to fly across the Atlantic Ocean, again within 72 hours, from any point in the USA, Canada or Newfoundland, and with no restriction on the nationality of entries. Of Sopwith's Atlantic aspirations, more in a later chapter; so for the moment we have to record that the dates eventually fixed for the 1913 Circuit of Britain event were 16-30 August. This was to be a most exacting affair, with 1,540 miles (2.478 km) to be covered in nine stages. Three of the four entries - Cody's 'Circuit' Waterplane; the Short S.68 of Frank McClean and Gus Smith; and the Radley-England Waterplane of James Radley and E. C. Gordon England were withdrawn. This left the Sopwith entry only, which, contrary to many expectations, turned out to be not a Bat Boat, but a new type of floatplane, clearly developed from the Anzani Tractor seaplane already described, though having a 100 hp six-cylinder all-British Green engine and four-bay wings of equal span.

Although built hurriedly, this fine new machine was of very handsome and businesslike appearance, its lines being enhanced by the fine aerodynamic entry afforded by the slim Green water-cooled engine, the radiators for which were disposed as large flat surfaces, one on each side of the fuselage between the wings. The centre section was left uncovered, and in the definitive (floatplane) version - for the aircraft was also built with a twin-wheel/twin-skid landing gear - the gap thus left had 'endplate' fairings. The primary object of the gap was to allow the crew to get out smartly in a crash, though some later Sopwith aeroplanes had 'fancy' centre sections for other reasons - notably clear view. The two seats were in tandem; construction was of wood, with fabric covering; the two main floats were of lenticular form; and the tail float was cylindrical.

The 1913 'Circuit' event turned out to be a sad affair all round. Cody had been killed at Laffan's Plain on 7 August, when his 'Hydro-biplane' broke up in the air (this likewise had a 100 hp Green engine); the Radley-England was without a suitable engine of any kind; and the Short was not ready in time. Although the 100 hp Green engine was almost invariably described as 'reliable', poor Cody had little chance to find out (in his particular installation the propeller was driven by a chain), and Sopwith, as intimated, was using an advanced radiator system. In any case, Fred Sigrist had plenty to occupy him in connection with the powerplant; and Harry Hawker, who was the pilot, and had his compatriot H. A. Kauper as passenger, fainted from inhaling exhaust fumes after leaving Yarmouth. Sopwith arranged for Sydney Pickles to take over as pilot; Pickles tried to start again, but from a sea so choppy that water got in to the tail float and elevator. Then the machine went back to Cowes, where longer exhaust pipes were fitted.

The contest now having been re-convened by the Daily Mail for 25 August, and Hawker having now recovered, the 'two Harries' - Hawker and Kauper - left the Solent at 5.30 am in calm and mist, and by the end of that day had set a new record for over-water flying. They alighted at Beadnell, Northumberland, at 7.40 in the evening - this notwithstanding an unscheduled alighting, occasioned by a burst exhaust pipe which had heated water-connections and boiled the water away, the radiator system being refilled at Seaham with sea-water. Thus the Green product, as well as the Sopwith, was able to continue next day, when Oban was the night-stop. At 5.42 am on the following day (27 August) this splendid outfit was once more getting under way; but a waterlogged float obliged a return for repair. In spite of this the new Sopwith pressed on to Larne (Antrim, Northern Ireland); but after flying on nearly to Dublin Hawker decided to alight to adjust valve-springs on the engine, his foot slipped on the rudder-bar, and the Sopwith fell into the sea off Loughshinny, a few miles north of Dublin. Hawker was unhurt, Kauper broke an arm; but 1.043 miles had been covered in 20 hr flying time, and the Daily Mail awarded Hawker a special prize of ?1,000 for his determination.

While recognising that the effort just described was very much a British affair, the present writer nevertheless ventures upon a little Empire rebuilding by noting what must be one of the most eloquent, though concise, tributes on record not only to the Sopwith aeroplane concerned but to its crew and their homeland. Thus a solitary resounding line in the ten-volume Angus & Robertson Australian Encyclopaedia: '1913 - H. Hawker and H. A. Kauper Sopwith seaplane - Daily Mail circuit of Britain - The two Australians crashed after 1,043 miles.'

Technically, the significance of this flight was in its demonstration of the long-distance capabilities of British seaplanes (just as the Tabloid was to show at Monaco what they could do in the way of speed); and a suitably impressed British Admiralty ordered a rebuilt example of the 1913 Circuit Seaplane which, in company with a Bat Boat I, made a brave show at the Naval Review of July 1914. By that time the comma-shaped rudder bore the number 151, and this very machine was later in service with No. 4 Wing, RNAS. It was reported at the time that No. 151 was flown on the Cuxhaven Raid of Christmas Day 1914 by Flt Cdr R. Ross; but though Robin Ross participated in that raid, some doubt exists concerning the identity of his aircraft especially so as all the seaplanes concerned were otherwise declared to have been Shorts, and also in view of Sir Arthur Longmore's testimony that Robin Ross later flew the (presumed) Sopwith Type C, a somewhat similar machine, in torpedo-dropping tests at Calshot.

That the airframe of the 1913 Circuit Seaplane (as we have already named the type concerned) has not been described in detail is due not only to the fact that few details have survived, but to the concentration of interest in its powerplant. This being so, it may be noted that the 100 hp Green six-cylinder engine, first publicly announced near the end of 1912 as having 'lately been placed upon the market by the Green Engine Syndicate, to whose specifications the engines are built in Great Britain [the country was always emphasised in connection with Green engines] by the Aster Engineering Co." weighed 442 lb complete and delivered its 100 hp at 1.150 rpm. 'Although the dead weight per horse-power is not of the lowest', it was observed, 'compared with rotating [sic] engines for instance, the economy in fuel and lubricating oil reduces the total load to be carried by a machine destined for extended journeying well below that of less efficient types."

That for 'extended journeying' a Sopwith/Green combination could indeed place Great Britain in the forefront was surely established by the effort of the Sopwith 1913 Circuit Seaplane. A landplane version of the same machine was first tested by Hawker on 4 October, 1913 - at Brooklands, it is hardly needful to add. On this occasion the rudder bar once again enters the story; for, finding himself caught in a down-current soon after take off, and realising the inevitability of a crash, Hawker deliberately removed his feet from the bar in order to brace himself. Thus, as the ensuing sideslip finished abruptly (near the Weybridge-Byfleet road) he sustained only fairly minor injuries.

Although the Green-engined landplane is said to have been repaired for competition flying, there could be confusion here with the Green-engined variant of the Three-seater, referred to in the appropriate chapter. (For an exposition of the complicated competitive scene towards the end of 1913 the reader is commended to Peter Lewis' Putnam book British Racing and Record-Breaking Aircraft - pages 76/77 especially).

By what must surely be the ultimate in paradox, the later Sopwith 1914 Circuit Seaplane existed in name only - and even so, apparently, as a landplane! Powered by a 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape engine, this was a trim-looking tandem two-seater, with the widely spaced cockpits having head-fairings between and behind; two-bay staggered wings, of equal span and aileron-equipped; and a twin-wheel landing gear, incorporating also two skids. The ailerons had inverse taper (increasing in chord towards the tips) and were interconnected by struts. Respecting engine installation and landing gear at least, this aeroplane, which was constructed to drawings marked "D3", resembled the Tabloid: but its real significance was that (the 1914 Circuit contest having been abandoned by reason of the war) the design was developed into the Folder Seaplane (Admiralty Type 807) which is separately described. There was, in any case, very strong Admiralty interest not only in the contest itself, which was to have started from the Admiralty yacht Enchantress (so closely associated with Winston Churchill) but in the individual entries. Totalling nine, these included a Bat Boat II to be flown by Howard Pixton, as Sopwiths' second string - and, of all things, a German D.F.W., Beardmore-built.

The nominated pilot for the Sopwith 1914 Circuit Seaplane was Victor Mahl, by this time prominent in the Sopwith team, and who himself tested the aircraft (as a landplane, at Brooklands) on 15 July, 1914. Of this aeroplane these brief particulars were given:

‘Immediately behind the engine are situated the petrol and oil tanks, whilst an additional supply of petrol is carried in another tank behind the passenger's seat. This is situated sufficiently far forward to provide a good view in a downward direction, whilst from the pilot's seat, placed as it is in line with the trailing edge of the lower plane, which has been cut away near the body, an excellent view is obtained in a downward and forward direction. By cutting away the trailing edge of the centre portion of the upper plane, the pilot is enabled to look upwards and forwards, so that it would appear that the arrangement of the pilot's seat and the staggered planes is such as to give the pilot, as nearly as possible in a machine of this type, an unrestricted view in all directions.

'The main planes are of the usual Sopwith type, and are very strongly built. Compression struts are fitted between the main spars in order to relieve the ribs of the strain of the internal cross-bracing. Ailerons are fitted to the tips of both upper and lower main planes, and are slightly wider than the remaining trailing portion of the wings in order to render them more efficient. The ailerons are operated through stranded cables passing round a drum on the control lever in front of the pilot's seat. The tail planes are of the characteristic Sopwith type, consisting of an approximately semi-circular tail plane, to the trailing edge of which is hinged a divided elevator. The chassis is of a substantial type, and the two main floats are sprung by means of leaf springs interposed between the rear of the float and the rear chassis struts, whilst the floats pivot round their attachment to the lower end of the front chassis struts. The floats are spaced a comparatively great distance apart, in order to render the machine more stable on the water. A tail float of the usual type takes the weight of the tail planes when the machine is at rest.'

Its obvious superficiality notwithstanding, the foregoing quotation is, in fact, quite significant - especially respecting the attention paid to field of view, for this was manifest likewise in the Type 807 (Folder) and the Two-seater Scout, both Admiralty types. What Sopwith were clearly trying to do was to reconcile tractor performance with pusher visibility an 'unrestricted view ... as nearly as possible in a machine of this type". But as the war was to prove (the most notable instance being the D.H.4) widely spaced cockpits, especially with petrol tankage between them, were not a paying proposition, though Sopwiths' preoccupation with field of view continued undiminished.

Although it has been stated that by the beginning of August 1914 larger vertical tail surfaces had been fitted to the (intended) 1914 Circuit Seaplane, and although such a modification was commonly associated with the fitting of floats - out of consideration for side area there is no firm evidence that floats were installed.

1913 Circuit Seaplane (100 hp Green)

Span 49 ft 6 in (15 m); length 31 ft (9.4 m); wing area 500 sq ft (46.5 sq m). Maximum weight 2.400 lb (1.090 kg). Cruising speed 65 mph (105 km/h).

1914 Circuit Seaplane (100 hp Gnome Monosoupape)

Span 36 ft 6 in (11.1 m); length with float landing gear 30 ft 10 in (9.4 m). Performance data not established.

Type 137

That some close association existed between this curious and obscure 'one-off’ Sopwith type and the 1914 Circuit Seaplane is apparent from its general appearance the non-folding wings (lightly staggered, and having inversely tapered ailerons) being the most obvious similarities. To a marked degree, however, the true derivation of the machine (numbered 137, and bearing the Admiralty type-designation that heads this chapter) is concealed by the unequal-span wings, with strut-braced upper extremities; by the bedazzling - even hypnotic! - effect of the huge roundels painted on the under-surfaces of the upper wings, as well as the lower ones; and most of all, perhaps by the entirely different engine installation.

The engine was, in fact, a water-cooled 120 hp Austro-Daimler, the deep frontal radiator for which appears to have been outsize-projecting, as it did, high above the engine itself. The bizarre appearance thus conveyed (which could, of course, have been accounted for by any of several considerations, among them water-clearance) was heightened by the echelon arrangement of exhaust ports in the heavily louvred side-cowlings. A long fore-and-aft member lower down and in line with the two cockpits was apparently a foot step. Behind and above the engine was what appears to have been a tank, substantially oblong in form; and on the rearmost inboard bracing strut was a wind-driven pump, or the like.

Here it is pertinent to note that the '120-hp Beardmore Austro-Daimler Aero Engine' (Beardmore having also obtained a licence to build the German D.F.W. biplane) was being promoted before the war by the Austrian Daimler [sic] Motor Co Ltd, of Great Portland Street, London-partly on the strength of Cody's success in the 1912 Military Trials, when using an engine of this general type. Further, a number of Royal Aircraft Factory designs were prepared round the 120 hp Austro-Daimler, and this same engine was, in fact, installed in the standard R.E.5 (to which - on reflection - the Sopwith Type 137 bore a certain resemblance). Conversely, however, the R.E.5 installation was a distinctly 'fancy' one, with open-fronted cowling and an internal radiator set far back in the fuselage.

Whatever its functions - intended or realized - No. 137 survived until some time in 1915, when it was overhauled by Pemberton Billing Ltd at Woolston, Southampton.

P.Lewis British Aircraft 1809-1914 (Putnam)

Sopwith 1913 Circuit Seaplane

Among the entries for the Daily Mail Circuit of Britain race, held from 16th to 30th August, 1913, was a tractor seaplane of the Sopwith company. The machine was a large four-bay biplane powered by a six-cylinder 100 h.p. Green engine and was flown in the £5,000 contest by H. G. Hawker and H. Kauper. The Sopwith was the only machine to take-off finally in the event, the other three entries having withdrawn. The rules of the trial stipulated that the distance of 1,540 miles was to be completed in three days from the start.

The slim, upright engine permitted a clean, tapered nose compared with the blunt front of the landplane version with its 80 h.p. Gnome, but the power plant gave continual trouble during the race. After two starts, Hawker managed to cover two-thirds of the course, but finally had to give up and was awarded a special personal prize of £ 1,000 for his determination and display of fine airmanship.

The radiators for the water-cooled Green were mounted on each side of the fuselage, and the centre section of the wings was left uncovered to offer easy egress for the crew in the event of a crash.

SPECIFICATION

Description: Two-seat tractor biplane seaplane. Wooden structure, fabric covered.

Manufacturers: Sopwith Aviation Co. Ltd., Kingston-on-Thames, Surrey.

Power Plant: 100 h.p. Green.

Dimensions: Span, 49 ft. 6 ins. Length, 31 ft. Wing area, 500 sq. ft.

Weights: Loaded, 2,400 lb.

Performance: Cruising speed, 65 m.p.h.

J.Bruce British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 (Putnam)

Sopwith Seaplane, Admiralty Type 137

PERHAPS the least-known of all the Sopwith types is this seaplane which had the official serial number 137. It was a comparatively small two-seater with two-bay wings of unequal span; the wings did not fold. The engine was a 120 h.p. Austro-Daimler, and had a flat frontal radiator.

The fuselage, wings and tail-unit were all typical of contemporary Sopwith practice. Large single-step floats of the pontoon type were fitted, and there was a tail-float to which a water-rudder was hinged.

The designed purpose of the machine is uncertain. It was probably intended to be a patrol seaplane, but may have been used as a trainer. It was still in service in 1915, when it was overhauled by Pemberton-Billing Ltd., at Woolston, Southampton.

The serial numbers 137 and 138 were allotted for Sopwith seaplanes. It is believed that No. 138 had a 200 h.p. Salmson engine, but the aircraft type is uncertain.

Журнал Flight

Flight, August 16, 1913.

THE SOPWITH TRACTOR WATERPLANE.

HAVING already achieved such remarkable success with his tractor-type land machine, Mr. Sopwith decided to enter a biplane of this type, fitted, of course, with floats instead of wheels, for the Daily Mail Race Round Britain, in preference to one of the Bat boat type, and in consideration of the large open stretches of sea which have to be negotiated, we are inclined to think that he has chosen wisely.

In its general outlines, this machine possesses the same smart business-looking appearance which characterizes the land machines, further enhanced perhaps by the tapering nose of the fuselage, allowed of by the installation of a 100 h.p. six-cylinder vertical type British Green engine, instead of the 80 h.p. Gnome motor with which the land machines are usually fitted. The fuselage, which is of rectangular section is built up in the usual way of four longerons of ash, connected by struts and cross members. In the rear part of the body these are made of spruce, while in front, where the weight of pilot, passenger and engine is concentrated, and where, therefore, greater strength is required, these members are made of ash. The main planes, which are very strongly built over main spars of solid spruce of I section are slightly staggered, and are also set at a dihedral angle in order to give the machine a certain amount of lateral stability. From a point just behind the pilot's seat back to the rudder post the fuselage is covered in with fabric, whilst the front portion is covered with aluminium, forming on top of the nose of the fuselage a very neat and cleanly designed cover over the motor. A very interesting detail in connection with the mounting of the Green engine forms the subject of one of the accompanying sketches which is self-explanatory. This method of joining the engine-bearer to the strut makes an enormously strong job, and this joint serves very well as an example of the thoroughness and attention to detail which is typical of Sopwith construction.

The main floats, which have been built by the Sopwith Aviation Co., are of the single step type and are built up of a framework of ash and spruce covered with a double skin of cedar. Two bulkheads divide the floats into three watertight compartments, so that should a float become damaged, causing one compartment to leak, the other two would still have sufficient buoyancy to prevent the float from sinking very deeply into the water. Two pairs of inverted V struts connect each float with a lower main plane, while another pair of struts running to the front part of the fuselage help to take the weight of the engine. Spruce is the material used for chassis as well as plane struts, the latter being hollowed out for lightness.

Inside the comparatively deep fuselage, where ample protection against the wind is afforded to pilot and passenger, are the two seats arranged tandem fashion, the pilot occupying the rear seat. In front of him are the controls, which consist of a rotatable hand wheel, mounted on a single central tubular column. Rotation of the wheel operates the ailerons, which are fitted to both top and bottom planes, and which are inter-connected. A to and fro movement operates the elevator, while a foot bar actuates the rudder. It should be noticed that the control cables are only exposed to the effects of the air and salt water for a very short length, the elevator cables entering the body just in front of the fixed tail plane and the rudder cables a couple of feet from the rudder post. The engine is supplied with petrol and oil from tanks situated under the passenger's seat, the capacity of the tanks being 45 gallons and 10 gallons respectively.

For the purpose of easy egress in case of a smash, the centre portion of the top plane has been left uncovered. In order to minimise end losses due to the air spewing out of the opening thus produced, what might be called baffle plates have been fitted to the inner ends of the wing.

These baffle plates have been made streamline in section, as it was found that an ordinary thin board would bend owing to the pressure of the air trying to escape past it. With full load of fuel and passengers on board the weight of the machine is 2,400 lbs., and her flying speed is 60 to 65 m.p.h.

Flight, August 23, 1913.

THE "DAILY MAIL" ROUND BRITAIN RACE.

"Enchantress," Royal Motor Yacht Club, Off Netley.

Friday afternoon.

THE days when the "Enchantress" was the centre of much competitive activity on Southampton Water in connection with the various motor boat trials that were held there have passed long since, but the floating Club House of the Royal Motor Yacht Club remains as the headquarters of that department of sport, and it is appropriate and courteous that they should have offered the hospitality of the ship in that capacity to the Royal Aero Club on the occasion of the start for the Daily Mail flying race.

With an event timed to start at six o'clock in the morning, it is a matter of convenience that one much appreciates to be on the spot over night, particularly when, as in this instance, the accommodation is of such a thoroughly comfortable order. Having arrived at midday, I found the officials had gone over to Ryde, in order to mark, for the purposes of identification, the various portions of the Sopwith hydro-biplane that is to be flown on the morrow by Mr. H. G. Hawker. This matter accomplished, they returned to the "Enchantress" with the news that no attempt at a start would be made before ten o'clock, owing to the fact that the site of the aeroplane shed in which the machine was housed was such as to make it inconvenient to float the craft before high tide. As a result, there entered into the scheme of things material the more alluring prospect of a reasonably long time in bed.

Saturday morning.

Hopes in this direction proved false, for at five o'clock visitors began to arrive at the gangway outside my cabin window, and I heard voices enquiring diligently for Mr. Perrin, the Secretary of the Royal Aero Club, while various local pressmen ventured a general request for information "about this flying business." After an hour of this sort of thing, I came to the conclusion that it was hopeless to pretend to rest, and the same thought must have struck others, for quite a number of those on board turned up to breakfast about half past six. Among the early visitors were the Mayor and Sheriff of Southampton, who had come down on the Harbour Board tug, a message over night warning them of the delayed start having miscarried.

Time dragged somewhat to the appointed hour, but the arrival of Lieut. Spencer Grey, R.N., on the Sopwith bat-boat, and the later arrival of Lieut. Travers, R.N., on a Borel hydro-monoplane, helped to relieve the situation. The attempt of the latter to get his machine hitched up to a boom alongside the "Enchantress" afforded an interesting demonstration of an important problem in connection with the use of seaplanes. Ultimately, the machine was made fast to a buoy nearer shore.

Ten o'clock arrived, and there was no sign of Hawker. Eleven o'clock struck, and still the expected machine had not put in an appearance. About half-past eleven, however, he was seen flying up the Channel, and in another minute or two he had alighted about half-way between the ship and the shore. Several boats put off to meet him, but most people remained aboard on the understanding that the official start would be timed as the machine passed in full flight near the ship. This was not in the regulations, but merely an idea that some people more or less adopted.

In the meantime, we watched the little group of boats from a distance, and presently saw them clear away from the machine. The engine was started, and at 11-47 the hydro-aeroplane sped along the water in the direction of the open sea. He was off. Without fuss and without an audible cheer, Hawker had started in the great trial. In a few seconds he and his machine were in the air, and almost before anyone had realised that the flight had begun, the machine itself was out of sight and the show was over.

Then followed the usual buzz of conversation, which was naturally mainly directed to the prospect of the pilot's successful accomplishment of his journey. He had 144 miles to fly in order to reach the first control at Ramsgate. This was followed by another 96-mile flight to Yarmouth. Then a journey of 150 miles to Scarborough. It was generally recognised that to have any chance of success he must get to Scarborough on the first day, although the total for the day's journey represented nearly 300 miles.

Sunday was to be a day on which flying was prohibited, but competitors were at liberty to repair their machines. It was evident, therefore, that the best policy would be to make the longest journey possible on Saturday, in order that the maximum work might be done before the arbitrary repairing time came into force.

From this point of view it was, therefore, unfortunate that the start had been made so late, and it appeared that the additional delay was due to difficulty in getting the compass properly arranged.

If the pilot made Scarborough on the Saturday night, he ought to fly as far as Oban on the Monday, the total distance for the second stage being 446 miles, including the Caledonian Canal, which is recognised as being probably one of the worst stretches in the circuit. On the Tuesday he would have to get from Oban to Dublin, which is a journey of 222 miles, and from Dublin to Falmouth, which is a further 280 miles, the day's journey being 500 miles. The importance of reaching Falmouth on the third night is in order to avoid a very long journey on the last day. To complete the circuit in time, Hawker would have to cross the finishing line at Southampton before 4 o'clock on Wednesday afternoon, and it would obviously be taking great chances to try and complete the whole distance from Dublin on the morning and early afternoon of that day.

Reckoning the circuit out in this manner, shows how difficult is the task which has been set for the Daily Mail prize, and the mere fact of the start having taken place so successfully is, at any rate, a credit to the British-built Green engine and the British-built Sopwith biplane. It is a matter for regret that other machines were not present to take part also. Mr. McClean, who was to have started, was apparently in difficulties on the Isle of Grain, and those on board the "Enchantress" heard no further news of him.

"OISEAU GRIS."

Details of the Flying.

As has already been stated, it was at thirteen minutes to twelve on Saturday morning when Mr. Hawker, on the Sopwith machine, rose from Southampton Water. Speeding down the reach, the machine rapidly faded from tight past Calshot, and then passing over the Solent, Mr. Hawker made for the open sea. Keeping well out from the land, at a fairly constant altitude of about 1,000 ft., Brighton, Eastbourne, and Dover were each passed in good time, and then the light southerly wind added its quota of assistance to the 100 h.p. Green engine, which has done its work throughout in such splendid style. Ramsgate, the first control, was reached at 2.11, the 144 miles of the first stage having been traversed in as many minutes. En route Mr. Hawker received an aerial welcome, Mr. Salmet, who was giving exhibition flights at Margate on his Bleriot, meeting him, and flying with him for a short distance. In the actual control, the Mayor of Ramsgate (Alderman Glynn), welcomed, per megaphone, Mr. Hawker, and announced that he had won the cup offered by the town for the first competitor to reach there. The Aero Club officials quickly made their inspection of the machine, and handed Mr. Hawker a clean waybill, so that as soon as the formalities, &c, had been completed, at two minutes past three the engine was started and the machine was away on the next stage to Yarmouth. The story of this part of the journey was but a repetition of what had occurred during the first stage, except for the fact that when crossing the mouth of the Thames there was a slight mist which obscured both banks. Still, Mr. Hawker was able to rely on his compass, and at Walton-on-the-Naze and at Clacton the crowds which assembled saw the machine in the distance going as well as ever.

On arrival at Yarmouth at 4.38 p.m., Mr. Hawker had another enthusiastic welcome. He said he was feeling well, but soon after he got ashore he collapsed, and the doctors diagnosed the case as one of sunstroke. This was borne out by Mr. Kaufer, his passenger, who said they had found the sun very trying, and unfortunately Mr Hawker had not taken the precaution to use goggles. Any further progress was impossible, and Mr. Sopwith at once set about arranging for a relief pilot. Eventually Mr. Sydney Pickles, who, like both Mr. Hawker and Mr. Kaufer comes from Australia undertook, with the generous consent of Messrs. Short Bros., to take the Sopwith on from Yarmouth. During Sunday which was a rest day, Mr. Pickles familiarised himself with the details of the machine, and on Monday morning was quite ready to continue the flight. The weather was, however, against the plucky pilot, and although he made a determined effort to get away at 5.30 a.m., the rough sea and ruing wind baulked him, and there was nothing left for it but to return to the shore, which, perhaps, was just as well, as up Scarborough way the "white horses" were so pronounced as to have washed away the buoys marking the control. The machine was presently dismantled and returned by rail to Cowes ready for a second attempt.

In the meantime, Mr. Frank McCIean and Messrs. Short Bros, had been working away with solid perseverance to remedy the obstinacy of the engine, the fault being ultimately found to be in a cracked cylinder. It was no sooner located than its replacement was arranged for by co-operation with Mr. Fred May, of the Green Engine Co. Its testing, until Mr. May was satisfied with its running, was then started, and at 2 a.m. on Thursday the engine was taken over to Grain Island, where the Short machine was comfortably resting, to be installed. All being well by Thursday evening, Mr. McCIean hoped to make for Southampton by way of the air, and there was the possibility of his making a start during Friday for the race itself.

As to Mr. Hawker, his health all the time was mending, so that on Thursday it was hoped he would be able to make his second attempt today (Saturday morning), early. Failing this, Mr. Sydney Pickles will be in readiness to take the pilot's seat, and endeavour to prove the sterling English worth of both the Sopwith machine and the Green engine. And may good luck come to either one of the plucky trio who are thus upholding the prestige of the home aeroplane industry.

Flight, August 30, 1913.

ROUND BRITAIN WATERPLANE FLIGHT.

DESPITE the fact that Mr. McClean's withdrawal on account of radiator trouble had robbed the event of the competitive interest, when Hawker on the Sopwith biplane started from Southampton Water on Monday morning for his second attempt to follow the British coast round, the progress of his flight was followed with as much eagerness as if he were the "favourite" among many. On the previous Saturday he had had the machine out for half an hour, and found it going as well as ever, while the noise from the engine had been appreciably reduced by lengthening the exhaust pipe. Monday morning opened clear and bright, but shortly after five o'clock a thick mist came up, and all that was seen of the Sopwith machine from the Enchantress was a glimpse of it as it sped over the starting line at half-past five. Once out of Southampton Water, clearer weather was found, and the pilot, this time carefully protected against the elements, steered a straight course down the Solent and out to the English Channel. Round the coast-line a good deal of mist was encountered, and Hawker had to rely on his compass at several points. The conditions were responsible for a slight reduction of speed compared with the previous flight over this stage, but Ramsgate was reached at eight minutes past eight, the 144 miles from Southampton having taken 159 mins. The formalities were completed well within the compulsory time-limit of half an hour, but some small adjustments took up a little more time, and it was eight minutes past nine ere the Sopwith machine was on its way to Yarmouth. The weather was still very thick, and little was seen of the land until Southwold was reached, but the sturdy machine made light of its task, and 1 hour 28 minutes flying saw the stage of 96 miles completed. The machine was taxied to its mooring, and Hawker boarded the motor boat of an Australian friend, Mr. A. Williamson, to enjoy a brief rest and some refreshment, while Mrs. Williamson presented a mascot in the shape of a spray of Australian eucalyptus leaves. This time it was the faithful mechanic, Kauper, who was feeling the strain of the flight.

At 11.44 the machine was once more on the wing and headed for Scarborough, 150 miles away. Still the mist was very trying, and off Cromer the side winds tested the air-worthiness of the Sopwith construction pretty thoroughly. Steering by the compass, however, and keeping at his usual height of about 1,000 ft., Hawker made a good course, and arrived at Scarborough at 2.42 p.m., his arrival being watched by a huge crowd, who had flocked into the town from the surrounding districts. After a brief period of rest on board Mr. W. Jackson's yacht "Naidia," he was back attending to his machine, and in view of the length of the next stage (218 miles). In Aberdeen, he arranged to make an intermediate stop at Berwick to pick up petrol. Soon after four everything was ready for the restart, and the crowd of boats was cleared out of the way to enable the machine to rise. At 4.22, it skimmed along the water for a short distance, and rose steadily to disappear rapidly in a northerly direction. On the way a leak developed in one of the water pipes, and a stop of 1 hr. 5 mins. had to be made at Seaham Harbour in order to effect an adjustment, and to replace the water lost. At 6.40, the journey was resumed, but the fates were against Hawker, and another descent had to be made, this time at Beadnell, about 20 miles south of Berwick. It was at 7.40 p.m., and several things combined to put an end to the day's flying, which had accounted for 495 miles. It was getting too dark to see the compass, the winds were very troublesome, and the engine started misfiring. On examination, however, there appeared to be nothing wrong with |the Green engine, the trouble being really with the water pipes. Hawker and Kauper decided to stay the night and make a. fresh start at 5 o'clock the next morning. As a matter of fact, however, it was five minutes past eight before the Sopwith biplane was again in the air, and 20 mins. later Berwick was passed. At 9.55 a call was made at Montrose for water, when adjustments took up just on half an hour. Aberdeen, the next control on the list, was reached at 10.58, the machine coming down from a height of about 1,500 ft. by a fine spiral vol plane. The weather now was splendid, and both pilot and mechanic declared themselves in fine form. This time just under an hour was spent in attention to men and machine, and at 11.52 the city of granite and marmalade was left behind. Cromarty was the next control, the 134 miles being traversed in 2 hrs. 13 mins., the trip being uneventful except for a tricky wind which was encountered when nearing Cromarty. It was recognised that the 94-mile stage from Cromarty to Oban, over the Caledonian Canal, would probably prove to be the most trying part of the whole route, and Hawker found that the conditions were certainly very erratic. The gusty winds in that mountainous region required very careful negotiating, and although Cromatty was left at five minutes past three, it was six o'clock before Oban was reached. It was then too late to think of starting on the long stage to Dublin, and the pilot and mechanic decided to take advantage of the opportunity of a good long rest, and get away early the next morning. They were astir at 4 a.m., and after a hurried breakfast were quickly at work inspecting the various parts of their machine. Soon after half-past five everything was ready, and at 5.42 Hawker was officially started for Dublin, although in view of the length of the stage he had arranged to call at Larne for petrol. The machine did not rise, however, with its accustomed readiness, and Hawker took her to the beach, about a mile out of Oban. It was there found that there was water in the floats, and an hour was spent in getting rid of it. Then a clean ascent was made, and a straight course steered down the Firth for the Irish coast. Scotland, however, could not be left so easily, and half an hour's stop had to be made at Kiells, in Argyllshire, in order to give a little attention to the engine. He was away again at 8.25, and at half-past nine made a splendid descent into Larne harbour. An hour and a half were spent at this point, the journey south being resumed at 11 o'clock. When only a few miles short of Dublin, Hawker feared that some of the valve springs of his motor were giving out, and he decided to come down and make an inspection. Again it seemed as if his luck had deserted him, for had he known that Mr. Green was waiting at Dublin, with new springs, he would have kept on. As it was, while making the spiral descent, his foot slipped from the rudder bar, apparently through his boot being greasy, he lost control of the machine, and she dropped to the water. Happily the first report that Hawker was injured proved unfounded, but Kauper had an arm broken and was cut about the head. Medical aid was quickly at hand, and he was taken in a motor car to the Mater Misericordiae Hospital, Dublin, where he is making as good progress as can be expected. The machine was smashed, but the catastrophe was not the fault of either the Sopwith machine or the Green engine. It was, as Hawker put it, "just a piece of ghastly bad luck." So ended the great flight when 1,043 miles out of the full distance of 1,540 miles had been covered. It remains to be added that the Daily Mail immediately announced that in recognition of his skill and courage a personal gift of L1,000 would be made to Hawker.

Flight, March 21, 1914.

THE OLYMPIA EXHIBITION.

THE EXHIBITS.

SOPWITH (THE SOPWITH AVIATION CO., LTD.). (44.)

<...>

Unfortunately Sopwith's were prevented, by lack of space, from exhibiting more than the one machine, and have had to be content with showing one of the main floats of their tractor hydro. This float is of similar construction, although of a different shape, lo that of the boat. The workmanship in this float, as well as in that of the complete machine, is of the very highest quality. The float shown is of the single-step type, and has five watertight compartments, each fitted with a very neat inspection door. These, as will be seen from the accompanying sketch, have bevelled edges, and are screwed down with butterfly nuts, the opening in the deck being rubber faced in order to provide a watertight joint. The combined trolley and turntable on which this machine is mounted greatly facilitates the operation of running the machine from the hangar down to the water and vice versa, and would appear to be an absolutely necessary accessory for the easy handling ashore of so heavy a craft as this.

An item in the exhibit on this stand which attracts considerable attention is the actual Green engine used by Mr. Hawker in his waterplane flight round Britain last summer. This engine, it will be remembered, flew 1,043 miles in 55 3/4 hours, or actual flying time 21 hours and 44 mins., which is claimed to be a world's record.