Книги

Centennial Perspective

J.Davilla

Italian Aviation in the First World War. Vol.3: Aircraft M-W

363

J.Davilla - Italian Aviation in the First World War. Vol.3: Aircraft M-W /Centennial Perspective/ (75)

Rampante! Th is painting by noted artist Russell Smith shows leading Italian ace Major Francesco Baracca flying his Spad 13. The rampant stallion was Baracca's personal insignia and was borrowed with Baracca's mother's permission by Enzo Ferrari for his racing cars after the war.

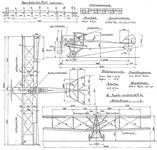

Macchi Parasol

In 1912 the Italian War Ministry launched a competition to select an aeroplane for the Italian forces. The French aircraft industry was the most successful in the world, and it is not surprising that the Italians would choose to initiate aircraft production in partner with one of that county’s more successful firms.

Carlo Felice Buzio, engineer Roberto Corsi, and capitano Costantino Biego di Costa Bissara, an artillery officer approached Giulio Macchi, an engineer living in Varese, about provided the necessary capital. Macchi agreed, and tasked Buzio and Corsi with negotiating with the French Nieuport firm an agreement to build their aircraft under licence.

On 1 May 1913 in a meeting with Leon Paul Maurice Bazaine (representing the Nieuport company of Paris), Paolo Molina (the legal representative of the Macchi brothers of Varese), and Giovanni De Martini (of the Wolsit company of Legnano), together Macchi and Corsi the Nieuport-Macchi firm was born.

The French would provide technical assistance and training for the nascent Italian aircraft industry. The also assisted in arranging for the supply of Gnome engines and many parts for the airframes.

The first three 100 hp Nieuports were assembled by seven men working in a Varese shed used to build automobiles. In 1913, the company was awarded an order for the construction of 56 Nieuport monoplanes, for which the 80-hp Gnome engines and many structural parts would be purchased direct from France.

These airplanes would be designated Ni.18 square meters or Nieuport 10, and were two-seaters intended for tactical reconnaissance, artillery spotting, and army cooperation duties.

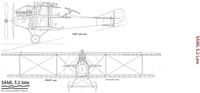

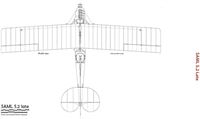

Meanwhile, drawing on the experience it had gained in building the Nieuports, Macchi was able to offer its first original design, the Parasol. The development of this aircraft was under the guidance of a test pilot named Clemente Maggiora, who had arrived at Varese in early 1914. The Parasol retained the same basic layout as the Nieuport 10, but had a parasol wing configuration, In the first year of the War, many aviators felt that an unobstructed view of the ground was necessary for reconnaissance and artillery spotting. Mounting the wing above the fuselage would be the most effective way to provide the observed with downward vision. This was also done with the Bleriot 11, where the shoulder mounted wing was replaced with a parasol on the Bleriot Type 11-2 Artillerie two-seater.

Other changes to the Macchi Parasol was the elimination of the cumbersome landing gear skid, which was replaced by a conventional tail skid. Some Parasols had a vertical surface mounted above the wing at the centreline.

On 4 December, 1914 a Macchi Parasol flown by Maggiora established three new world altitude records: 1. 4 December 1914 - 8,500 ft (2700 m) with two passengers (Count Patriarca and pioneering aviator Zanibelli) 2. 19 December 1914 - 12,300 ft (3750 m) in 38 minutes with one passenger

3. March 1915 - 12,430 ft (3790 m) with one passenger

Operational Service

Nieuport-Macchi built 56 Nieuport 10s (for details see entry under Nieuport 4), as well as the 42 Macchi-Parasols. During the first months of the War two squadriglias using the type were assigned artillery spotting duties. A squadriglia equipped with Parasols for artillery co-operation was operational in the second half June of 1915 at Pordenone, later displaced to Medeuzza the following July. Assigned to the service of 3a Armata (Carso and Adriatic), it was particularly active over Gorizia. In the June and July 1915 the Parasol performed sporadic bombing missions to little effect. Therefore, they were fitted with R.T. Rouzet wireless units.

The aircraft were removed from frontline service in November 1915.The pilot’s had complained that the aircraft was unstable and could not fly high enough to avoid AAA.

The Macchi Parasols were not up to the task of operating in a combat environment, so in November the unit converted to Caudron G.3s.

The Parasol had a strong structure and could be quickly disassembled for transport, but it was difficult to fly. The failure of the Parasol doomed the company’s chances of a large and lucrative contract for their first original design.

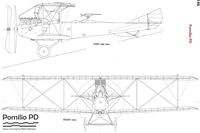

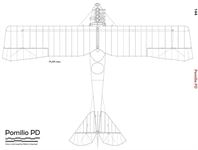

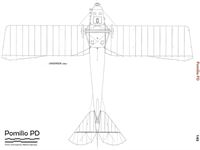

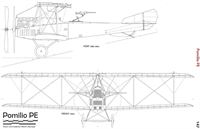

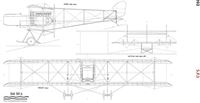

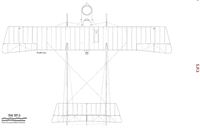

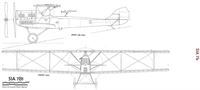

Macchi-Parasol two-seat reconnaissance aircraft with one 80-hp Gnome engine

Wingspan 13,00 m; length 7,20 m; height 3,10 m; wing area 24,0 sq m

Empty weight 400 kg; payload; 260 kg; loaded weight 660 kg

Maximum speed 125 km/h; climb to 1000 m in 10 minutes; climb to 2,000 m in 26 minutes; ceiling 12,430 ft (3790 m) with one passenger, range 400 km

A total of 42 built

In 1912 the Italian War Ministry launched a competition to select an aeroplane for the Italian forces. The French aircraft industry was the most successful in the world, and it is not surprising that the Italians would choose to initiate aircraft production in partner with one of that county’s more successful firms.

Carlo Felice Buzio, engineer Roberto Corsi, and capitano Costantino Biego di Costa Bissara, an artillery officer approached Giulio Macchi, an engineer living in Varese, about provided the necessary capital. Macchi agreed, and tasked Buzio and Corsi with negotiating with the French Nieuport firm an agreement to build their aircraft under licence.

On 1 May 1913 in a meeting with Leon Paul Maurice Bazaine (representing the Nieuport company of Paris), Paolo Molina (the legal representative of the Macchi brothers of Varese), and Giovanni De Martini (of the Wolsit company of Legnano), together Macchi and Corsi the Nieuport-Macchi firm was born.

The French would provide technical assistance and training for the nascent Italian aircraft industry. The also assisted in arranging for the supply of Gnome engines and many parts for the airframes.

The first three 100 hp Nieuports were assembled by seven men working in a Varese shed used to build automobiles. In 1913, the company was awarded an order for the construction of 56 Nieuport monoplanes, for which the 80-hp Gnome engines and many structural parts would be purchased direct from France.

These airplanes would be designated Ni.18 square meters or Nieuport 10, and were two-seaters intended for tactical reconnaissance, artillery spotting, and army cooperation duties.

Meanwhile, drawing on the experience it had gained in building the Nieuports, Macchi was able to offer its first original design, the Parasol. The development of this aircraft was under the guidance of a test pilot named Clemente Maggiora, who had arrived at Varese in early 1914. The Parasol retained the same basic layout as the Nieuport 10, but had a parasol wing configuration, In the first year of the War, many aviators felt that an unobstructed view of the ground was necessary for reconnaissance and artillery spotting. Mounting the wing above the fuselage would be the most effective way to provide the observed with downward vision. This was also done with the Bleriot 11, where the shoulder mounted wing was replaced with a parasol on the Bleriot Type 11-2 Artillerie two-seater.

Other changes to the Macchi Parasol was the elimination of the cumbersome landing gear skid, which was replaced by a conventional tail skid. Some Parasols had a vertical surface mounted above the wing at the centreline.

On 4 December, 1914 a Macchi Parasol flown by Maggiora established three new world altitude records: 1. 4 December 1914 - 8,500 ft (2700 m) with two passengers (Count Patriarca and pioneering aviator Zanibelli) 2. 19 December 1914 - 12,300 ft (3750 m) in 38 minutes with one passenger

3. March 1915 - 12,430 ft (3790 m) with one passenger

Operational Service

Nieuport-Macchi built 56 Nieuport 10s (for details see entry under Nieuport 4), as well as the 42 Macchi-Parasols. During the first months of the War two squadriglias using the type were assigned artillery spotting duties. A squadriglia equipped with Parasols for artillery co-operation was operational in the second half June of 1915 at Pordenone, later displaced to Medeuzza the following July. Assigned to the service of 3a Armata (Carso and Adriatic), it was particularly active over Gorizia. In the June and July 1915 the Parasol performed sporadic bombing missions to little effect. Therefore, they were fitted with R.T. Rouzet wireless units.

The aircraft were removed from frontline service in November 1915.The pilot’s had complained that the aircraft was unstable and could not fly high enough to avoid AAA.

The Macchi Parasols were not up to the task of operating in a combat environment, so in November the unit converted to Caudron G.3s.

The Parasol had a strong structure and could be quickly disassembled for transport, but it was difficult to fly. The failure of the Parasol doomed the company’s chances of a large and lucrative contract for their first original design.

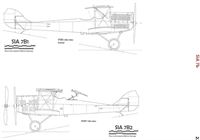

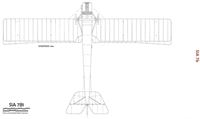

Macchi-Parasol two-seat reconnaissance aircraft with one 80-hp Gnome engine

Wingspan 13,00 m; length 7,20 m; height 3,10 m; wing area 24,0 sq m

Empty weight 400 kg; payload; 260 kg; loaded weight 660 kg

Maximum speed 125 km/h; climb to 1000 m in 10 minutes; climb to 2,000 m in 26 minutes; ceiling 12,430 ft (3790 m) with one passenger, range 400 km

A total of 42 built

Macchi L.1

Inspired by a captured Austro-Hungarian seaplane, the Macchi L.1 would provide the Regia Marina with an effective defense against the flying boats of that same country. It would also lead to the rise of the Macchi firm which is, under the title Aermacchi, still producing successful aircraft to this day.

On 27 May 1915, L 40 suffered a broken crankshaft which resulted in a forced landing near Volano. Alerted by a local constable, the crew were easily captured. The Lohner was sent to the Porto Corsini naval air station for evaluation.

The Lohner L 40 had been ordered by the Austro-Hungarian Navy under contract AE 000. It had a 140-hp Hiero engine on delivery, later 150-hp Rapp engines were also used. It had arrived in Pola on 31 December 1914 and operated from the seaplane stations at Pola, Sebenico from February 18-23, 1915. On 23 February 1915 during a flight to Pola it made an emergency landing due to lack of petrol at Medolino; the pilot and plane were rescued by mine-layer Chamaleon (Chameleon). It was repaired at Pola and on 28 May 1915 had participated in an attack along with L 44, L 46, L 47, L 48 and L 49 on Venice due to engine failure. It was during this raid that the aircraft force landed and was seized by the Italians.

The commanding officer of the Ferrara airship station, tenente di vascello (Naval Lieutenant) Guido Scelsi, took the time to carefully examine the Austrian aircraft and found it to be a superior design, clearly more advance than the motley collection of seaplanes then used by the Regia Marina. On 31 May, Scelsi recommended that the Regia Marina build a series of ten Lohner flying boats.

Macchi’s technical co-director Carlo Felice Buzio and his staff built and flew a copy in 'one month and three days’. The new seaplane obviously could not use the same engine as the captured example, so a 150-hp Isotta-Fraschini V4 engine, was used. It was tested by Giovanni Roberti di Castelvero and was sent to the seaplane station on Lake Varese.

These tests led to an order for 48 machines on September 1915 plus another 200 in 1916. Eventually it would deliver nearly 140 L.1s, 31 in 1915 and 109 in 1916. Ship manufacturers such as Baglietto in Varazze and Picchiotti in Viareggio (Lucca), and the Zari aircraft firm were the most important subcontractors.

Macchi fitted out the hulls, constructed the wings, and installed the engine at Masnago. The seaplanes were tested at Schiranna.

Copies of the Austrian L-types were numbered in the 101 to 200 range. As the first four L.1s were delivered to the Regia Marina they received serials L.101, L.102, L.103, and L.104. Their deliveries were finished on 12 December.

L.105 through L.108 were delivered in the first week in October, then the sequence restarted at L.169 on 19 October. This skip in the numbering sequence resulted in a stern warning to Macchi to adhere to the original numbering guidelines, and the normal sequence resumed.

Operational Service

By the end of December 1915 Lohners were based at:

Stations

Brindisi, 1 Macchi L.1

Grado, 2 Macchi L.1

Porto Corsini, 4 Macchi L.1

Venice, 4 Macchi L.1

Ship RN Europa

1 Macchi L.1

In the second half of 1916 the structure of Italian aviation was as follows:

Stations

Brindisi - 332 sorties in 1916, 4 Macchi L.1

Grado - 136 sorties in 1916, 6 Macchi L.1

Porto Corsini - 44 sorties in 1916, 1 Macchi L.1

Taranto -13 Macchi L.1

Varano - 265 sorties in 1916, 5 Macchi L.1

Venice - 242 sorties in 1916, 8 Macchi L.1

Ship RN Europa

6 Macchi L.1

The L.1s were used for the mundane, but important missions, of coastal patrol usually lasting three and a half hours.

On 4 May 1916, 2° capo Guido Jannello and his observer torpediniere Dante Falconi flew L124 against five Austro-Hungarian flying boats attacking Brindisi. Jannello claimed to have hit one of them. This victory was awarded to Jannello as the first victory for Italian naval aviation; Austro-Hungary did not record any losses that day.

On 19 July 1916 L157, which was apparently captured by the Austrians and pressed into service.

Brindisi utilized four aircraft in June 1916 (L135, L148, L195 and L196), three in December 1916 (L164, L205 and L214) and again four in March 1917 (L164, L214, L227 and L233) as trainers.

On 26 September 1916, Brindisi sent four L.1s and three FBAs to bomb Durazzo where they set fire to a steamer, a hangar, buildings and eight wagons on the road to Tirana. L120 was shot down.

During 1916 53 L.1s were lost representing half of the number of aircraft built. Very few of the losses were in combat, most were due to accidents or aircraft SOC due to breakdowns.

The Italians had one seaplane-carrying ship in the early part of the war, the RN Europa, which had replaced the Elba in November 1915. Four L.1s were deployed initially and there were six at the end of the year. The ship was moored in the Albanian harbour of Valona, serving as a floating air base. According to Varialle, the possibility of launching Lohners or FBAs on ships’ decks was studied in December 1916 and June 1917, but was found to be too technically demanding to pursue. On 1 April 1916, cannon-armed Lohners L 186 and L 191 flew to Samano Point, alighted and blew up the coal stockpile, telephones and other equipment at thee Austrian base.

As the more mature L.3s became available in 1917, the L.1s were relegated to the 6° Gruppo Scuole for use as trainers. The Gruppo consisted of five seaplane schools at Sesto Calende, Naples, Orbetello, Taranto and Passignano sul Trasimeno, the latter two being largely equipped with Lohners.

The main L.1 training units were at Orbetello, Passignano sul Trasimento, and Taranto. Of these, the most important base was at Taranto, which in the first half of 1916 had eight L.1s, reaching 13 in late 1916, but dropping to a single L.1 in mid-1917. By the end of 1917, the number of L.1s with the school had risen to seven.

The attrition rate for seaplane trainers must have been very high as ten L.1s were lost between 20 October 1916 and 30 July 1918.

According to one seaplane student by 1917 the Lohners (L.1s and L.2s) were obsolete, requiring full power and a long take off run to leave the water.

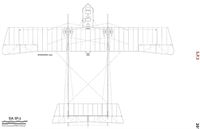

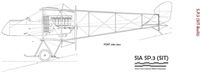

Macchi L.1 Two-Seat Patrol Flying Boat with One 150-hp Isotta-Fraschini V4 Engine

Wingspan 16.2 m, length 10.4 m, height 3.5 m; wing area 46 sq m

Empty weight 1,159 kg; loaded weight 1,780 kg; payload 600 kg

Maximum speed 105 km/h; climb to 2,000 m in 30 minutes; range 630 km

Armament included twin-barrelled Revelli light machine guns, a single heavy gun and various combinations of light bombs under the wings

Approximately 140 built

Macchi L.2

Operational experience soon showed that the L.1 lacked the performance for air defence duties. To this end, Macchi developed the lightened L.1 derivative known to the Regia Marina as LC (for Lohner Celere or Corsa, indicating Fast Lohner). The company was awarded a contract for ten L.2, fitted with hulls provided by Zari and Baglietto and serialled LC 251-260. The entire batch was apparently delivered by May 1916.

The new design retained the basic L.1 airframe but with a four bay wing. The empty weight was reduced by 250 kg.

Varriale has suggested the L.2 may have been influenced by a Lohner T1 L 83 captured on 2 February 1916. Although the L.2 had a higher top speed a 140 km, performance degraded rapidly over time. The ceiling declined from the reported 2,000 m to as little as 700 m in the older airframes. The hull and engine supports failed, as did the magnetos and fuel pumps.

Operational service

1916

Brindisi, 6 Macchi L.2

Venice, 3 Macchi L.2

Ship RN Europa, 1 Macchi L.2

As they were of no use in combat, the L.2s were sent to training units. By late 1917 only a handful (the official history says four) L.2s remained in service, down from the seven that were at the Taranto school at the start of the year.

L.2s ended its career with the training units of 6° Gruppo Scuole. This comprised five seaplane schools at Sesto Calende, Naples, Orbetello, Taranto and Passignano sul Trasimeno.

Macchi L.2 Two-Seat Patroll Flying Boat with One 150-hp Isotta-Fraschini V4 Engine

Wingspan 16.2 m, length 10.6 m, height 3.16 m; wing area 46 sq m

Empty weight 1,000 kg; loaded weight 1,450 kg; payload 450 kg

Maximum speed 140 km/h; climb to 2,000 m in 19 minutes; 3,000 meters in 30 minutes; range 600 km; endurance 4 hours

Approximately 10 built

Macchi L.3 (M.3)

Macchi’s L.2 had proved unequal to the task of providing a defense against the Lohner seaplanes. As the L.2 was a slightly modified L.1, a more radical departure from the preceding L types was needed.

Developed in 1916 by the Macchi seaplane division at Schiranna under the direction of Felice Buzio, the Macchi L.3 was a two/three-seat single-step flying-boat, which had unequal-span biplane wings developed from those of the L.2, but with a hull and tailplane of entirely new design. The hull was more streamlined and the tailplane, strut-mounted above the hull, was to become a characteristic of Macchi flying-boats.

In 1917 the original L.3 designation was changed to M.3 in recognition of the difference in concept from the original Lohner-inspired Macchi machines. However, the official naval aviation history still refers to them as “L.3s”.

The Macchi L.3 was significantly lighter than the L.1 or L.2 due to its low empty weight. On 10 October 1916 an M.3 operating from Lake Varese established a world time- to-height record for seaplanes by climbing to 5,400 m in 14 minutes.

Some 200 M.3s were built and used in the Adriatic for a wide variety of missions including bombing, reconnaissance, patrol and escort; the type was even used as a fighter until the appearance of the M.S single-seater in 1917. Several M.3s also participated in commando-style raids behind the Austrian lines.

The M.3s were held in high esteem by the pilots of the Italian navy. They made many bombing raids on the naval bases of Pola and Cattaro and pioneered aerial photography with frequent missions over these bases as well as Trieste.

Operational Service

1917

Seaplane Stations

Brindisi - 7 L.3

Cascina Farello - 7 L.3s

Otranto - 5 L.3s

Santa Maria di Leuca - 3 L.3s

Siracusa - 3 LAs

Varano - 8 L.3

Venice - 28 L.3s

Training Units - 74 L.3s

Most L.3s (M.3s) were based at Venice to help counter the attacks by Austro-Hungarian flying boats.

Later during 1917 the concept of the naval squadriglia (squadron) was introduced, with a numbering that started from 251 for the seaplanes, leaving the numbers from 201 to for other types of units.

Reconnaissance

251 - L.3 - Venice; S. Andrea

252 - L.3 - Venice; S. Andrea

253 - L.3 - Venice; S. Andrea

259 - L.3 - Venezia; S. Andrea

265 - L.3 - Brindisi

1918

In 1918 the L.3s had been largely replaced by M.5s; many were now serving in a training capacity.

Seaplane Stations

Brindisi - 8 L.3s

Venice - 30 L.3s

Training units

Bolesna -1 L.3

Taranto - 13 L.3s

Naval Squadriglias

Reconnaissance

251 - L.3 - Venice; S. Andrea

252 - L.3 - Venice; S. Andrea

253 - L.3 - Venice; S. Andrea

259 - L.3 - Venezia; S. Andrea

265 - L.3 - Brindisi

Postwar

Postwar the type remained in service with training units until 1924. A number were sold to the Swiss company Ad Astra Aero and were converted to take two passengers on charter flights and joy rides from the Swiss lakes. The passengers were seated side-by-side behind a large windscreen, with the pilot in a raised, open cockpit behind them.

Macchi L.3/M.3 Two-Seat Reconnaissance/Bomber Flying Boat with One 160-hp Isotta-Fraschini V.4B Engine

Wingspan 15.95 m; length 9.97 m; height 3.33 m; wing area 45 m2

Maximum take-off weight was 2,976 lb (1350 kg)

Maximum speed of 90 mph (145 km/h) and range of 280 miles (450 km), climb to 1,000 m in 5.30 minutes; to 4,000 m in 38 minutes; ceiling 6,000 m

Armament comprised a flexible 7.7-mm (0.303-in) Fiat machine-gun or a light cannon; four light bombs could also be carried.

A total of 200 built.

Inspired by a captured Austro-Hungarian seaplane, the Macchi L.1 would provide the Regia Marina with an effective defense against the flying boats of that same country. It would also lead to the rise of the Macchi firm which is, under the title Aermacchi, still producing successful aircraft to this day.

On 27 May 1915, L 40 suffered a broken crankshaft which resulted in a forced landing near Volano. Alerted by a local constable, the crew were easily captured. The Lohner was sent to the Porto Corsini naval air station for evaluation.

The Lohner L 40 had been ordered by the Austro-Hungarian Navy under contract AE 000. It had a 140-hp Hiero engine on delivery, later 150-hp Rapp engines were also used. It had arrived in Pola on 31 December 1914 and operated from the seaplane stations at Pola, Sebenico from February 18-23, 1915. On 23 February 1915 during a flight to Pola it made an emergency landing due to lack of petrol at Medolino; the pilot and plane were rescued by mine-layer Chamaleon (Chameleon). It was repaired at Pola and on 28 May 1915 had participated in an attack along with L 44, L 46, L 47, L 48 and L 49 on Venice due to engine failure. It was during this raid that the aircraft force landed and was seized by the Italians.

The commanding officer of the Ferrara airship station, tenente di vascello (Naval Lieutenant) Guido Scelsi, took the time to carefully examine the Austrian aircraft and found it to be a superior design, clearly more advance than the motley collection of seaplanes then used by the Regia Marina. On 31 May, Scelsi recommended that the Regia Marina build a series of ten Lohner flying boats.

Macchi’s technical co-director Carlo Felice Buzio and his staff built and flew a copy in 'one month and three days’. The new seaplane obviously could not use the same engine as the captured example, so a 150-hp Isotta-Fraschini V4 engine, was used. It was tested by Giovanni Roberti di Castelvero and was sent to the seaplane station on Lake Varese.

These tests led to an order for 48 machines on September 1915 plus another 200 in 1916. Eventually it would deliver nearly 140 L.1s, 31 in 1915 and 109 in 1916. Ship manufacturers such as Baglietto in Varazze and Picchiotti in Viareggio (Lucca), and the Zari aircraft firm were the most important subcontractors.

Macchi fitted out the hulls, constructed the wings, and installed the engine at Masnago. The seaplanes were tested at Schiranna.

Copies of the Austrian L-types were numbered in the 101 to 200 range. As the first four L.1s were delivered to the Regia Marina they received serials L.101, L.102, L.103, and L.104. Their deliveries were finished on 12 December.

L.105 through L.108 were delivered in the first week in October, then the sequence restarted at L.169 on 19 October. This skip in the numbering sequence resulted in a stern warning to Macchi to adhere to the original numbering guidelines, and the normal sequence resumed.

Operational Service

By the end of December 1915 Lohners were based at:

Stations

Brindisi, 1 Macchi L.1

Grado, 2 Macchi L.1

Porto Corsini, 4 Macchi L.1

Venice, 4 Macchi L.1

Ship RN Europa

1 Macchi L.1

In the second half of 1916 the structure of Italian aviation was as follows:

Stations

Brindisi - 332 sorties in 1916, 4 Macchi L.1

Grado - 136 sorties in 1916, 6 Macchi L.1

Porto Corsini - 44 sorties in 1916, 1 Macchi L.1

Taranto -13 Macchi L.1

Varano - 265 sorties in 1916, 5 Macchi L.1

Venice - 242 sorties in 1916, 8 Macchi L.1

Ship RN Europa

6 Macchi L.1

The L.1s were used for the mundane, but important missions, of coastal patrol usually lasting three and a half hours.

On 4 May 1916, 2° capo Guido Jannello and his observer torpediniere Dante Falconi flew L124 against five Austro-Hungarian flying boats attacking Brindisi. Jannello claimed to have hit one of them. This victory was awarded to Jannello as the first victory for Italian naval aviation; Austro-Hungary did not record any losses that day.

On 19 July 1916 L157, which was apparently captured by the Austrians and pressed into service.

Brindisi utilized four aircraft in June 1916 (L135, L148, L195 and L196), three in December 1916 (L164, L205 and L214) and again four in March 1917 (L164, L214, L227 and L233) as trainers.

On 26 September 1916, Brindisi sent four L.1s and three FBAs to bomb Durazzo where they set fire to a steamer, a hangar, buildings and eight wagons on the road to Tirana. L120 was shot down.

During 1916 53 L.1s were lost representing half of the number of aircraft built. Very few of the losses were in combat, most were due to accidents or aircraft SOC due to breakdowns.

The Italians had one seaplane-carrying ship in the early part of the war, the RN Europa, which had replaced the Elba in November 1915. Four L.1s were deployed initially and there were six at the end of the year. The ship was moored in the Albanian harbour of Valona, serving as a floating air base. According to Varialle, the possibility of launching Lohners or FBAs on ships’ decks was studied in December 1916 and June 1917, but was found to be too technically demanding to pursue. On 1 April 1916, cannon-armed Lohners L 186 and L 191 flew to Samano Point, alighted and blew up the coal stockpile, telephones and other equipment at thee Austrian base.

As the more mature L.3s became available in 1917, the L.1s were relegated to the 6° Gruppo Scuole for use as trainers. The Gruppo consisted of five seaplane schools at Sesto Calende, Naples, Orbetello, Taranto and Passignano sul Trasimeno, the latter two being largely equipped with Lohners.

The main L.1 training units were at Orbetello, Passignano sul Trasimento, and Taranto. Of these, the most important base was at Taranto, which in the first half of 1916 had eight L.1s, reaching 13 in late 1916, but dropping to a single L.1 in mid-1917. By the end of 1917, the number of L.1s with the school had risen to seven.

The attrition rate for seaplane trainers must have been very high as ten L.1s were lost between 20 October 1916 and 30 July 1918.

According to one seaplane student by 1917 the Lohners (L.1s and L.2s) were obsolete, requiring full power and a long take off run to leave the water.

Macchi L.1 Two-Seat Patrol Flying Boat with One 150-hp Isotta-Fraschini V4 Engine

Wingspan 16.2 m, length 10.4 m, height 3.5 m; wing area 46 sq m

Empty weight 1,159 kg; loaded weight 1,780 kg; payload 600 kg

Maximum speed 105 km/h; climb to 2,000 m in 30 minutes; range 630 km

Armament included twin-barrelled Revelli light machine guns, a single heavy gun and various combinations of light bombs under the wings

Approximately 140 built

Macchi L.2

Operational experience soon showed that the L.1 lacked the performance for air defence duties. To this end, Macchi developed the lightened L.1 derivative known to the Regia Marina as LC (for Lohner Celere or Corsa, indicating Fast Lohner). The company was awarded a contract for ten L.2, fitted with hulls provided by Zari and Baglietto and serialled LC 251-260. The entire batch was apparently delivered by May 1916.

The new design retained the basic L.1 airframe but with a four bay wing. The empty weight was reduced by 250 kg.

Varriale has suggested the L.2 may have been influenced by a Lohner T1 L 83 captured on 2 February 1916. Although the L.2 had a higher top speed a 140 km, performance degraded rapidly over time. The ceiling declined from the reported 2,000 m to as little as 700 m in the older airframes. The hull and engine supports failed, as did the magnetos and fuel pumps.

Operational service

1916

Brindisi, 6 Macchi L.2

Venice, 3 Macchi L.2

Ship RN Europa, 1 Macchi L.2

As they were of no use in combat, the L.2s were sent to training units. By late 1917 only a handful (the official history says four) L.2s remained in service, down from the seven that were at the Taranto school at the start of the year.

L.2s ended its career with the training units of 6° Gruppo Scuole. This comprised five seaplane schools at Sesto Calende, Naples, Orbetello, Taranto and Passignano sul Trasimeno.

Macchi L.2 Two-Seat Patroll Flying Boat with One 150-hp Isotta-Fraschini V4 Engine

Wingspan 16.2 m, length 10.6 m, height 3.16 m; wing area 46 sq m

Empty weight 1,000 kg; loaded weight 1,450 kg; payload 450 kg

Maximum speed 140 km/h; climb to 2,000 m in 19 minutes; 3,000 meters in 30 minutes; range 600 km; endurance 4 hours

Approximately 10 built

Macchi L.3 (M.3)

Macchi’s L.2 had proved unequal to the task of providing a defense against the Lohner seaplanes. As the L.2 was a slightly modified L.1, a more radical departure from the preceding L types was needed.

Developed in 1916 by the Macchi seaplane division at Schiranna under the direction of Felice Buzio, the Macchi L.3 was a two/three-seat single-step flying-boat, which had unequal-span biplane wings developed from those of the L.2, but with a hull and tailplane of entirely new design. The hull was more streamlined and the tailplane, strut-mounted above the hull, was to become a characteristic of Macchi flying-boats.

In 1917 the original L.3 designation was changed to M.3 in recognition of the difference in concept from the original Lohner-inspired Macchi machines. However, the official naval aviation history still refers to them as “L.3s”.

The Macchi L.3 was significantly lighter than the L.1 or L.2 due to its low empty weight. On 10 October 1916 an M.3 operating from Lake Varese established a world time- to-height record for seaplanes by climbing to 5,400 m in 14 minutes.

Some 200 M.3s were built and used in the Adriatic for a wide variety of missions including bombing, reconnaissance, patrol and escort; the type was even used as a fighter until the appearance of the M.S single-seater in 1917. Several M.3s also participated in commando-style raids behind the Austrian lines.

The M.3s were held in high esteem by the pilots of the Italian navy. They made many bombing raids on the naval bases of Pola and Cattaro and pioneered aerial photography with frequent missions over these bases as well as Trieste.

Operational Service

1917

Seaplane Stations

Brindisi - 7 L.3

Cascina Farello - 7 L.3s

Otranto - 5 L.3s

Santa Maria di Leuca - 3 L.3s

Siracusa - 3 LAs

Varano - 8 L.3

Venice - 28 L.3s

Training Units - 74 L.3s

Most L.3s (M.3s) were based at Venice to help counter the attacks by Austro-Hungarian flying boats.

Later during 1917 the concept of the naval squadriglia (squadron) was introduced, with a numbering that started from 251 for the seaplanes, leaving the numbers from 201 to for other types of units.

Reconnaissance

251 - L.3 - Venice; S. Andrea

252 - L.3 - Venice; S. Andrea

253 - L.3 - Venice; S. Andrea

259 - L.3 - Venezia; S. Andrea

265 - L.3 - Brindisi

1918

In 1918 the L.3s had been largely replaced by M.5s; many were now serving in a training capacity.

Seaplane Stations

Brindisi - 8 L.3s

Venice - 30 L.3s

Training units

Bolesna -1 L.3

Taranto - 13 L.3s

Naval Squadriglias

Reconnaissance

251 - L.3 - Venice; S. Andrea

252 - L.3 - Venice; S. Andrea

253 - L.3 - Venice; S. Andrea

259 - L.3 - Venezia; S. Andrea

265 - L.3 - Brindisi

Postwar

Postwar the type remained in service with training units until 1924. A number were sold to the Swiss company Ad Astra Aero and were converted to take two passengers on charter flights and joy rides from the Swiss lakes. The passengers were seated side-by-side behind a large windscreen, with the pilot in a raised, open cockpit behind them.

Macchi L.3/M.3 Two-Seat Reconnaissance/Bomber Flying Boat with One 160-hp Isotta-Fraschini V.4B Engine

Wingspan 15.95 m; length 9.97 m; height 3.33 m; wing area 45 m2

Maximum take-off weight was 2,976 lb (1350 kg)

Maximum speed of 90 mph (145 km/h) and range of 280 miles (450 km), climb to 1,000 m in 5.30 minutes; to 4,000 m in 38 minutes; ceiling 6,000 m

Armament comprised a flexible 7.7-mm (0.303-in) Fiat machine-gun or a light cannon; four light bombs could also be carried.

A total of 200 built.

A Macchi L.3 of 259a Squadriglia stationed in Venice. Note the unit marking of the Lion of St. Mark so artistically rendered. This aircraft was part of a bombing raid of Pola on 17th July 1918. The US Naval aviators would often join their Italian counterparts in the missions against the SFS-Pola.

Macchi M.4

The final stage in the evolution of Macchi flying-boats derived from the L.1, the Macchi M.4 appeared in 1917. It was more powerful than the M.3, being tested with both a 300-hp (224-kW) Fiat A.12 engine and a 420-hp (313-kW) F.T.; with the latter it had a maximum speed of 118 mph (190 km/h). One of the two examples built was used in tests with a Vickers COW gun for anti-submarine attack, but it was armed normally with a single machine-gun and carried a heavier bomb load than the M.3. With the end of the war and appearance of the M.9, development was abandoned.

Macchi M.4 Two-Seat Reconnaissance and Bomber Flying Boat with One 300-hp Fiat A.12 Engine

Wing span 16,00 m; length 9,95 m; height 3,22 m; wing area 49,00 sq m

Empty weight. 1100 kg (2,420 lbs) payload 600 kg (1,320 lbs.);

Loaded weight 1700 kg (3,740 lbs.).

Maximum speed 165 km/h (102 m.p.h.); ceiling 4000 m (13,120 ft), range 660 km (410 mis.), endurance 4 h.

Armament was 1 machine gun and two lance bombs (2 lancia-bombe).

Two built

The final stage in the evolution of Macchi flying-boats derived from the L.1, the Macchi M.4 appeared in 1917. It was more powerful than the M.3, being tested with both a 300-hp (224-kW) Fiat A.12 engine and a 420-hp (313-kW) F.T.; with the latter it had a maximum speed of 118 mph (190 km/h). One of the two examples built was used in tests with a Vickers COW gun for anti-submarine attack, but it was armed normally with a single machine-gun and carried a heavier bomb load than the M.3. With the end of the war and appearance of the M.9, development was abandoned.

Macchi M.4 Two-Seat Reconnaissance and Bomber Flying Boat with One 300-hp Fiat A.12 Engine

Wing span 16,00 m; length 9,95 m; height 3,22 m; wing area 49,00 sq m

Empty weight. 1100 kg (2,420 lbs) payload 600 kg (1,320 lbs.);

Loaded weight 1700 kg (3,740 lbs.).

Maximum speed 165 km/h (102 m.p.h.); ceiling 4000 m (13,120 ft), range 660 km (410 mis.), endurance 4 h.

Armament was 1 machine gun and two lance bombs (2 lancia-bombe).

Two built

Macchi M.5

The escalating naval air war between Austro-Hungary and Italy resulted in bomb raids on major coastal cities and naval bases; i.e. Pola and Venice. The performance of the reconnaissance and bomber seaplanes necessitated the creation of a dedicated seaplane bomber force using singleseat fighters. While the KuK could occasionally provide fighter escorts for these vulnerable seaplanes, it was soon recognized that the Regia Marina would need to provide fighter escorts for their own aircraft.

Several solutions were posited. The Ansaldo license built 100 Sopwith Baby floatplane for use as an interim fighter until an indigenous design could be completed. However, by the time the Baby was available, the M.5 would already be in production.

It was hoped that the Macchi L.2 and L.3 would serve as a stop gap until a purpose-designed fighter was available. The L.3 would prove to be of limited usefulness as a fighter, while the L.2’s performance degraded so quickly in service that it had to be withdrawn from operational units and used as a trainer.

Fortunately, the Italian Macchi M.5 would prove to be the solution to the Regia Marina’s requirement. Indeed, to would be produced in greater numbers than any other seaplane fighter.

Macchi’s design used the available 160-hp Isotta-Fraschini V.4B engine, the same as used on the preceding L.3 flying boat. There could be no hope of counting on increased engine power to provide superior performance; the M.5 would have to depend on its single seat design to reduce weight and on aerodynamic refinements to further boost performance. The M.5 was smaller, not only because it had just one crew member, but also to reduce weight and, hopefully, boost speed and maneuverability. Compared to the L.1, the fuselage length was 20% shorter and the wingspan was 25% smaller. These changes reduced the empty weight by 25%.

Armament was to be a single machine-gun mounted on post ahead of the windscreen. On pre-production machines the armament would be changed to allow for two machine guns to be carried. There was no need for the complexity or weight of a synchronization system, as the M.5 would have the engine mounted in a pusher configuration.

Prototype testing resulted in changes to the design. The step was moved up by 30 cm, the bow was shortened by 20 cm. The machine gun was now faired into the forward fuselage. The fin and rudder were placed 30 cm forward. The engine was covered by an aluminum nacelle. The radiator was now a single vertical piece, replacing the dual radiators of the prototype.

A contract for ten machines was issued on 17 February 1917.

Testing of initial production M.5s began in May 1917. Test pilots praised its superior speed and rate of climb.

Eight of the ten M.5s ordered had been delivered by 30 June 1917. They would be used as fighters and reconnaissance machines (According to Varriale these were known as “M.M.” in contemporary documents).

Operational testing led to further modifications to the tail surfaces. The fin now had a square outline and was mounted directly to the fuselage so the control lines could be located internally and, therefore, be protected from salt water corrosion. The wing tip floats had been mounted flush to the wing tips in the prototype; they were now enlarged and carried on struts. The internal structure of the wing was altered; there were now 27 ribs, instead of 17, for each wing panel. The steel internal structure of the ailerons was now made of wood with a 150% increase in the number of ribs. It is unclear why these changes were introduced; perhaps some of these alterations were intended to boost production.

As noted above, the M.5 would be used as fighter with a (in production aircraft) non synchronized twin machine gun armament. But the M.5 was also expected to used as a high speed photo reconnaissance aircraft. To that end, a vertical camera was mounted behind a moveable panel located in the lower hull.

At least one M.5 was modified to carry a 25,4-mm Fiat gun in place of the machine gun armament; 255a Squadriglia had one such aircraft which carried serial 7080 (see entry below).

The total number of M.5s ordered was 420, of which approximately 348 were actually built. Nieuport-Macchi received an order for 340 and Aeromarittima in Naples was to manufacture 80.

Variants

M.5 mod - The success of the M.5’s successor, the M.7, resulted in an order for 320 aircraft, as well as a reduction in M.5 orders. This provided an opportunity for Macchi to suggest that the unfinished 70 or so airframes could be converted to a pseudo-M.7 with meant fitting them with the new M.7 wing. This hybrid aircraft would be know as M.5 mod (modification). Varialle notes that there was no intention of fitting these airframes with the M.7’s 250-hp Isotta Fraschini V6 engine. However, postwar, a 1923 order called for 32 M.5s mod to, indeed, be upgraded with 250-hp Isotta Fraschini V6 engines.

Acceptance flights were carried out in the summer of 1918, and at least two appear to have reached operational units (13132 with 260a Squadriglia in late November 1918 and 13153 at Brindisi in early December). By March 1919 some had also reached the 264a in Ancona.

M.S a.s. - Long-range version the M.5 mod. Known as M.5 a.s. (a.s. = autonomia speciale 'special range’). It had an endurance of five hours, a 30% increase over the standard M.5 mod. The reason for the alteration is not known, but as the M.5 was intended as fast reconnaissance aircraft, the longer endurance would make it a high-speed, long-range reconnaissance aircraft, similar to the SVAs in service with the Aviazione. At least three were completed with serials 13139, 13152, and 13153.

Production

M.M. - 10 ordered 4866 to 4875

M.5 - 50 ordered 7056 to 7195

M.5 - 77 ordered 7225 to 7302

M.5 - 166 ordered 13088 to 13185; M.5 mod. is in this serial range as 13129 to 13185

M.5 - 44 ordered 14078 to 14122

Total production was 348 aircraft

List based on Varialle, Macchi M.S.

Operational Service

By 1 July, aircraft 4866 and 4867 were on strength of the 251a Squadriglia in Venice (I Reparti Dell’Aviazione Italian della Grande Guerra suggest that these became operational much later).

The aircraft were used in their intended fighter escort role and their performance represented a marked improvement over the L.3s then in service. The Fiat gun had a tendency to jam, but this was a common problem with Italian aviation weapons and was usually due to problems with the ammunition and not the gun, itself.

The Regia Marina supplied fighter aircraft in small numbers to operational units in to provide escort during reconnaissance and bombing missions. As the M.5s were produced, they were sent in small numbers to the units that faced the gravest threat from Austro-Hungarian fighters.

Eventually, production reached the point it was possible to create squadriglias with a dedicated fighter role.

Designated as Gruppo Idrovolanti da Caccia (Seaplane Fighter Group), 260a and 261a Squadriglias. It is noteworthy that these units were based in Venice, where the need for fighters was the most critical.

The M.5 was intended to be replaced by M.7s in 1918, but, once again, Italian aviation lagged behind the needs of the frontline units only a small number of M,7s arrived in time to enter service. As a result, the M.5 was the main Italian fighter seaplane of the war.

Postwar

On 30 September 1919, there were 242 M.5 and 29 M.5 mod, but only 87 were serviceable - all but one were with Regia Marina squadriglias. Naval Stations now operated a mix of aircraft types; the surviving M.5s and M.7s would be used to provide escort for reconnaissance and bomber aircraft.

Varriale reports that at least one M.5 was used by the aviation element of the Italian insurgent forces in Fiume in 1919.

When the Regia Aeronautica was formed on 28 March 1923, the surviving M.5s were based at Brindisi and Pola. The 1923-24 seaplane program moved the two M.5 squadriglias to Taranto and Venezia, each with nine aircraft plus reserves.

Foreign Service

United States

Two M.5s were sent to the U.S.Navy by the Italian government in the hope of enticing the Navy to procure more. These were assigned BuAe (Bureau of Aeronautics) numbers A-5574 and A-5575 after the war.

The Italian government eagerly welcomed the support of the U.S. Navy in the Adriatic, including U.S. Naval Aviation. The Italians decided to turn over the Porto Corsini and Pescara Stations to them. Porto Corsini was, in the end, the only base to be given to the U.S. On 1 August 1918 the new American unit had three M.5s and five M.8 flying boat fighters (plus ten FBAs). Seven M.5s were not operational initially, so the number available fluctuated between three and six. Varriale reports that the Italians had turned over 15 M.5s, so this gives some idea of the state of the machines.

Although displeased with the condition of the base, the Navy began combat operations on 21 August.

On 21 August 21; M.8 19008, while being escorted by four M.5s took off on the missions. Four Phonixes intercepted the Americans. George Ludlow, in M.5 13015, along with Austin Parker and Charles H. Hammann engaged the Austrian aircraft. The M.5s of Dudley Voorhees, could not follow because his machine gun jammed. Ludlow attacked the lead Phonix; A.102, which he claimed as destroyed although the Austrians stated the aircraft was destroyed when its fuel system spontaneously ignited. Stephan Woleman was attacked by A.118. Hits from 8-mm machine guns ignited his engine and the Macchi burst into flames. Hammann landed on the water to help his friends; Ludlow sunk his plane before boarding Hammann’s plane. Harmann would later receive the Medal of Honor for this action; the first to be earned by an aviator of the U.S. Navy.

The next day M.S No.7293 and M.5 No.7294 flown by Ensign Johansen and Seargent Guarniere made a reconnaissance of Pola.

As the M.5s were worn out, and it took considerable effort to make them operational. Six new M.5 were shipped to Porto Corsini on 6 September.

263a continued to attack Pola, but as the number of M.8 bombers was limited, they could only stage a few bombing raids. Pola was attacked on October 22 with 11 aircraft, including at least two M.5s: 7293 and 13076. On the afternoon of 25 October, 263a’s airplanes joined with other aircraft based at Venice to make a large bombing raid on Pola.

On 2 November four M.5s were sent on an armed patrol of the Pola station; these were 13076, 13085, 13086, and 13089. The patrol failed to reach their target due to the weather, and 13076 had to briefly set down due to equipment failure. Eventually, all the M.5s made it back to base.

On January 1st, 1919 the Station was formally taken back by the Regia Marina.

The two M.5s still in the United States had brief careers. One crashed when it entered a spin; it killed Ensign Hammann before he could be awarded the Medal of Honor.

The c/n numbers of the M.5s supplied to the U.S. Navy were 7225, 7229, 7241, 7251, 7268, 7293, 7294, 7299, 13015, 13021, 13027, 13047, 13075, 13076, 13077, 13079, 13085, 13086, 13088, 13089, 13091, 13102, 13129.

Macchi M.6

The Macchi M.6 was a variant of the M.5 in which the Nieuport firm’s favored sesquiplane layout was eliminated. In its place, there were equal span, single bay wings without sweepback. As the struts were located on the outer section of the wings, auxiliary supports made of steel tubing were placed on either side of the engine nacelle.

Designated M.6, the aircraft was found not to offer any advantages over the M.5. Further development was, therefore, abandoned. However, the M.6 did influence the design of the next Macchi aircraft, the M.7.

Macchi M.6 Single-Seat Flying Boat Fighter with One 160-hp Isotta Fraschini V.4B Engine

Wing area. 29,00 sq m

Empty weight 760 kg; payload; loaded weight 1,030 kgs

Maximum speed 189 km/h; climb to 4000 m in 20 minutes; endurance 3 hours.

Armament was one 7,7-mm Vickers machine gun

One built

The escalating naval air war between Austro-Hungary and Italy resulted in bomb raids on major coastal cities and naval bases; i.e. Pola and Venice. The performance of the reconnaissance and bomber seaplanes necessitated the creation of a dedicated seaplane bomber force using singleseat fighters. While the KuK could occasionally provide fighter escorts for these vulnerable seaplanes, it was soon recognized that the Regia Marina would need to provide fighter escorts for their own aircraft.

Several solutions were posited. The Ansaldo license built 100 Sopwith Baby floatplane for use as an interim fighter until an indigenous design could be completed. However, by the time the Baby was available, the M.5 would already be in production.

It was hoped that the Macchi L.2 and L.3 would serve as a stop gap until a purpose-designed fighter was available. The L.3 would prove to be of limited usefulness as a fighter, while the L.2’s performance degraded so quickly in service that it had to be withdrawn from operational units and used as a trainer.

Fortunately, the Italian Macchi M.5 would prove to be the solution to the Regia Marina’s requirement. Indeed, to would be produced in greater numbers than any other seaplane fighter.

Macchi’s design used the available 160-hp Isotta-Fraschini V.4B engine, the same as used on the preceding L.3 flying boat. There could be no hope of counting on increased engine power to provide superior performance; the M.5 would have to depend on its single seat design to reduce weight and on aerodynamic refinements to further boost performance. The M.5 was smaller, not only because it had just one crew member, but also to reduce weight and, hopefully, boost speed and maneuverability. Compared to the L.1, the fuselage length was 20% shorter and the wingspan was 25% smaller. These changes reduced the empty weight by 25%.

Armament was to be a single machine-gun mounted on post ahead of the windscreen. On pre-production machines the armament would be changed to allow for two machine guns to be carried. There was no need for the complexity or weight of a synchronization system, as the M.5 would have the engine mounted in a pusher configuration.

Prototype testing resulted in changes to the design. The step was moved up by 30 cm, the bow was shortened by 20 cm. The machine gun was now faired into the forward fuselage. The fin and rudder were placed 30 cm forward. The engine was covered by an aluminum nacelle. The radiator was now a single vertical piece, replacing the dual radiators of the prototype.

A contract for ten machines was issued on 17 February 1917.

Testing of initial production M.5s began in May 1917. Test pilots praised its superior speed and rate of climb.

Eight of the ten M.5s ordered had been delivered by 30 June 1917. They would be used as fighters and reconnaissance machines (According to Varriale these were known as “M.M.” in contemporary documents).

Operational testing led to further modifications to the tail surfaces. The fin now had a square outline and was mounted directly to the fuselage so the control lines could be located internally and, therefore, be protected from salt water corrosion. The wing tip floats had been mounted flush to the wing tips in the prototype; they were now enlarged and carried on struts. The internal structure of the wing was altered; there were now 27 ribs, instead of 17, for each wing panel. The steel internal structure of the ailerons was now made of wood with a 150% increase in the number of ribs. It is unclear why these changes were introduced; perhaps some of these alterations were intended to boost production.

As noted above, the M.5 would be used as fighter with a (in production aircraft) non synchronized twin machine gun armament. But the M.5 was also expected to used as a high speed photo reconnaissance aircraft. To that end, a vertical camera was mounted behind a moveable panel located in the lower hull.

At least one M.5 was modified to carry a 25,4-mm Fiat gun in place of the machine gun armament; 255a Squadriglia had one such aircraft which carried serial 7080 (see entry below).

The total number of M.5s ordered was 420, of which approximately 348 were actually built. Nieuport-Macchi received an order for 340 and Aeromarittima in Naples was to manufacture 80.

Variants

M.5 mod - The success of the M.5’s successor, the M.7, resulted in an order for 320 aircraft, as well as a reduction in M.5 orders. This provided an opportunity for Macchi to suggest that the unfinished 70 or so airframes could be converted to a pseudo-M.7 with meant fitting them with the new M.7 wing. This hybrid aircraft would be know as M.5 mod (modification). Varialle notes that there was no intention of fitting these airframes with the M.7’s 250-hp Isotta Fraschini V6 engine. However, postwar, a 1923 order called for 32 M.5s mod to, indeed, be upgraded with 250-hp Isotta Fraschini V6 engines.

Acceptance flights were carried out in the summer of 1918, and at least two appear to have reached operational units (13132 with 260a Squadriglia in late November 1918 and 13153 at Brindisi in early December). By March 1919 some had also reached the 264a in Ancona.

M.S a.s. - Long-range version the M.5 mod. Known as M.5 a.s. (a.s. = autonomia speciale 'special range’). It had an endurance of five hours, a 30% increase over the standard M.5 mod. The reason for the alteration is not known, but as the M.5 was intended as fast reconnaissance aircraft, the longer endurance would make it a high-speed, long-range reconnaissance aircraft, similar to the SVAs in service with the Aviazione. At least three were completed with serials 13139, 13152, and 13153.

Production

M.M. - 10 ordered 4866 to 4875

M.5 - 50 ordered 7056 to 7195

M.5 - 77 ordered 7225 to 7302

M.5 - 166 ordered 13088 to 13185; M.5 mod. is in this serial range as 13129 to 13185

M.5 - 44 ordered 14078 to 14122

Total production was 348 aircraft

List based on Varialle, Macchi M.S.

Operational Service

By 1 July, aircraft 4866 and 4867 were on strength of the 251a Squadriglia in Venice (I Reparti Dell’Aviazione Italian della Grande Guerra suggest that these became operational much later).

The aircraft were used in their intended fighter escort role and their performance represented a marked improvement over the L.3s then in service. The Fiat gun had a tendency to jam, but this was a common problem with Italian aviation weapons and was usually due to problems with the ammunition and not the gun, itself.

The Regia Marina supplied fighter aircraft in small numbers to operational units in to provide escort during reconnaissance and bombing missions. As the M.5s were produced, they were sent in small numbers to the units that faced the gravest threat from Austro-Hungarian fighters.

Eventually, production reached the point it was possible to create squadriglias with a dedicated fighter role.

Designated as Gruppo Idrovolanti da Caccia (Seaplane Fighter Group), 260a and 261a Squadriglias. It is noteworthy that these units were based in Venice, where the need for fighters was the most critical.

The M.5 was intended to be replaced by M.7s in 1918, but, once again, Italian aviation lagged behind the needs of the frontline units only a small number of M,7s arrived in time to enter service. As a result, the M.5 was the main Italian fighter seaplane of the war.

Postwar

On 30 September 1919, there were 242 M.5 and 29 M.5 mod, but only 87 were serviceable - all but one were with Regia Marina squadriglias. Naval Stations now operated a mix of aircraft types; the surviving M.5s and M.7s would be used to provide escort for reconnaissance and bomber aircraft.

Varriale reports that at least one M.5 was used by the aviation element of the Italian insurgent forces in Fiume in 1919.

When the Regia Aeronautica was formed on 28 March 1923, the surviving M.5s were based at Brindisi and Pola. The 1923-24 seaplane program moved the two M.5 squadriglias to Taranto and Venezia, each with nine aircraft plus reserves.

Foreign Service

United States

Two M.5s were sent to the U.S.Navy by the Italian government in the hope of enticing the Navy to procure more. These were assigned BuAe (Bureau of Aeronautics) numbers A-5574 and A-5575 after the war.

The Italian government eagerly welcomed the support of the U.S. Navy in the Adriatic, including U.S. Naval Aviation. The Italians decided to turn over the Porto Corsini and Pescara Stations to them. Porto Corsini was, in the end, the only base to be given to the U.S. On 1 August 1918 the new American unit had three M.5s and five M.8 flying boat fighters (plus ten FBAs). Seven M.5s were not operational initially, so the number available fluctuated between three and six. Varriale reports that the Italians had turned over 15 M.5s, so this gives some idea of the state of the machines.

Although displeased with the condition of the base, the Navy began combat operations on 21 August.

On 21 August 21; M.8 19008, while being escorted by four M.5s took off on the missions. Four Phonixes intercepted the Americans. George Ludlow, in M.5 13015, along with Austin Parker and Charles H. Hammann engaged the Austrian aircraft. The M.5s of Dudley Voorhees, could not follow because his machine gun jammed. Ludlow attacked the lead Phonix; A.102, which he claimed as destroyed although the Austrians stated the aircraft was destroyed when its fuel system spontaneously ignited. Stephan Woleman was attacked by A.118. Hits from 8-mm machine guns ignited his engine and the Macchi burst into flames. Hammann landed on the water to help his friends; Ludlow sunk his plane before boarding Hammann’s plane. Harmann would later receive the Medal of Honor for this action; the first to be earned by an aviator of the U.S. Navy.

The next day M.S No.7293 and M.5 No.7294 flown by Ensign Johansen and Seargent Guarniere made a reconnaissance of Pola.

As the M.5s were worn out, and it took considerable effort to make them operational. Six new M.5 were shipped to Porto Corsini on 6 September.

263a continued to attack Pola, but as the number of M.8 bombers was limited, they could only stage a few bombing raids. Pola was attacked on October 22 with 11 aircraft, including at least two M.5s: 7293 and 13076. On the afternoon of 25 October, 263a’s airplanes joined with other aircraft based at Venice to make a large bombing raid on Pola.

On 2 November four M.5s were sent on an armed patrol of the Pola station; these were 13076, 13085, 13086, and 13089. The patrol failed to reach their target due to the weather, and 13076 had to briefly set down due to equipment failure. Eventually, all the M.5s made it back to base.

On January 1st, 1919 the Station was formally taken back by the Regia Marina.

The two M.5s still in the United States had brief careers. One crashed when it entered a spin; it killed Ensign Hammann before he could be awarded the Medal of Honor.

The c/n numbers of the M.5s supplied to the U.S. Navy were 7225, 7229, 7241, 7251, 7268, 7293, 7294, 7299, 13015, 13021, 13027, 13047, 13075, 13076, 13077, 13079, 13085, 13086, 13088, 13089, 13091, 13102, 13129.

Macchi M.6

The Macchi M.6 was a variant of the M.5 in which the Nieuport firm’s favored sesquiplane layout was eliminated. In its place, there were equal span, single bay wings without sweepback. As the struts were located on the outer section of the wings, auxiliary supports made of steel tubing were placed on either side of the engine nacelle.

Designated M.6, the aircraft was found not to offer any advantages over the M.5. Further development was, therefore, abandoned. However, the M.6 did influence the design of the next Macchi aircraft, the M.7.

Macchi M.6 Single-Seat Flying Boat Fighter with One 160-hp Isotta Fraschini V.4B Engine

Wing area. 29,00 sq m

Empty weight 760 kg; payload; loaded weight 1,030 kgs

Maximum speed 189 km/h; climb to 4000 m in 20 minutes; endurance 3 hours.

Armament was one 7,7-mm Vickers machine gun

One built

The superlative Macchi M.5 fighter. This aircraft in the hands of the aggressive Italian naval aviators from the Gruppo Idrocaccia Venezia wrested command of the skies over the Northern Adriatic Sea from the Austrian naval aviators. The fighter with the "angry cat" insignia belonged to Luigi Bologna.

Macchi M.5 M 7248 on its beaching dolley. The M.5 was the best flying boat fighter to see combat during WWI.

Another view of the Macchi M.5 flown by Lieutenant Haviland, commander of the flying unit at Porto Corsini.

Ensign Haviland, commander of the flying unit at Porto Corsini, stands beside his colorful Macchi M.5 fighter.

Ensign Ludlow's Macchi M.5 undergoes engine maintenance.The Latin phrase on the hangar refers to the star above: It saves whereupon it shines.

Ensign George H. Ludlow in front of a colorful Macchi M.5 fighter flown by the US Navy from Porto Corsini.

Landsman for Quartermaster Charles Hammann with his Macchi M.5 fighter at Porto Corsini. Hammann received the Medal of Honor for rescuing George Ludlow when he landed two miles from Pola to pick him from the water after he was shot down.

The colorful Macchi M.5 fighter of the Commander of 261a squadriglia, Domenico Arcidiancono over Venice. Courtesy of Ray Rimell; artist is Danilo Renzulli.

Macchi M.12

The identity of the M.10 and M.11 are unknown.

A reconnaissance/bomber flying-boat, the Macchi M.12 represented an attempt to achieve a worthwhile improvement in speed and defensive armament by comparison with contemporary the M.9. Designed in late 1918, the M.12 was powered by a single 450-hp Ansaldo-San Giorgio 4 E/28 engine driving a pusher propeller, but had an unconventional wide forward hull which terminated aft of the wings. Attached to the rear of the hull were two booms, which supported a twin-fin-and-rudder tail unit. The crew comprised a pilot and two gunners, the latter in cockpits in the bow and behind the wing. This arrangement gave the rear gunner a wide field of fire above and below the tailplane. All cockpits were interconnected by an internal passage which permitted the nose and tail gunners to switch positions.

The M.12 carried a radio, a camera and a bomb load of up to 882 lb (400 kg), plus two 7.7mm (0.303-in) machineguns.

The aircraft’s mission was to have been high speed reconnaissance and bombing.

Produced just at the end of the war, it does not appear that more than one or two examples were ordered by the Regia Marina. There is no record of any M.12s reaching front line units for operational evaluation.

The M.12bis of 1919 was a civil version with provision for three passengers in an enclosed cabin. It had a cruising speed of 103 mph (165 km/h).

Macchi M.12 Three-Seat Long-Range Flying Boat with One 450-hp Ansaldo-San Giorgio 4 E/ 28 Engine

Wingspan was 17.00 m; length 10.90 m; height 3,66 m; wing area 61.0 sq m

Empty weight 1,780 kg; payload 780 kg; loaded weight 2560 kg

Maximum speed 190 km/h; climb to 3,000 m in 28 minutes 30 seconds; range 750 to 950 km; ceiling 5,500 m

Armament was 2 7,7-mm Fiat machine guns in nose and tail positions and four 162 mm mines

The identity of the M.10 and M.11 are unknown.

A reconnaissance/bomber flying-boat, the Macchi M.12 represented an attempt to achieve a worthwhile improvement in speed and defensive armament by comparison with contemporary the M.9. Designed in late 1918, the M.12 was powered by a single 450-hp Ansaldo-San Giorgio 4 E/28 engine driving a pusher propeller, but had an unconventional wide forward hull which terminated aft of the wings. Attached to the rear of the hull were two booms, which supported a twin-fin-and-rudder tail unit. The crew comprised a pilot and two gunners, the latter in cockpits in the bow and behind the wing. This arrangement gave the rear gunner a wide field of fire above and below the tailplane. All cockpits were interconnected by an internal passage which permitted the nose and tail gunners to switch positions.

The M.12 carried a radio, a camera and a bomb load of up to 882 lb (400 kg), plus two 7.7mm (0.303-in) machineguns.

The aircraft’s mission was to have been high speed reconnaissance and bombing.

Produced just at the end of the war, it does not appear that more than one or two examples were ordered by the Regia Marina. There is no record of any M.12s reaching front line units for operational evaluation.

The M.12bis of 1919 was a civil version with provision for three passengers in an enclosed cabin. It had a cruising speed of 103 mph (165 km/h).

Macchi M.12 Three-Seat Long-Range Flying Boat with One 450-hp Ansaldo-San Giorgio 4 E/ 28 Engine

Wingspan was 17.00 m; length 10.90 m; height 3,66 m; wing area 61.0 sq m

Empty weight 1,780 kg; payload 780 kg; loaded weight 2560 kg

Maximum speed 190 km/h; climb to 3,000 m in 28 minutes 30 seconds; range 750 to 950 km; ceiling 5,500 m

Armament was 2 7,7-mm Fiat machine guns in nose and tail positions and four 162 mm mines

Macchi M.14

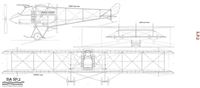

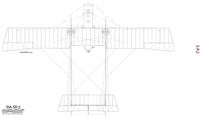

The M.14 single-seat sesquiplane fighter was designed by Alessandro Tonini. While certainly not a direct copy of the Hanriot HD.1s that Macchi had produced under license, it did bear an uncanny likeness of that machine. It was of all wood construction and had a Warren truss type interplane bracing. The engine was a 110-hp Le Rhone 9J nine-cylinder rotary. The armament was two synchronized 7,7-mm Vickers guns.

Technical

Wings - two spar wooden wing covered in fabric. Ailerons on the upper wing only. The wings had a marked dihedral on the upper wing, while the lower wings were straight. The “W” shaped struts (joined at the mid portion of the lower wing on each side, was later seen in other Italian fighter designs, most notably the CR.42.

Fuselage - similar to the HD.1. The fuselage sides were flat.

Power Plant - The engine was a 110-hp Le Rhone 9J rotary engine for the M.14 bis fighter and a 80-hp engine or the M.14 fighter trainer. The 90-hp version may have never been built.

Landing Gear - Landing gear with faired struts an additional fairing covering the landing gear strut. These struts were intended to act as an auxiliary airfoil.

Testing

Flight testing commenced in the spring of 1918, but the prototype was destroyed in June of that year when it crashed, killing Clemente Maggiora. Aircraft 20931 underwent evaluation in 1919 at Montecelio. By December 1919 there were seven M.14s at Montecelio. However, no additional orders were forthcoming. The M.14’s performance was considered satisfactory, but not notably superior to the other Italian fighters then in service. The ten M.14s were employed as advanced trainers; these carried serials 20931 to 20940. At least one (20935) appeared on the civil register carrying serial I-BADG.

Foreign Service

Spain - An example was purchased in Spain. According to the then Lieutenant Gomez Spencer, who flew the sole prototype at Getafe around 1922, it cost the Aeronautica Militar only 6,000 pesetas. It was equipped with a 110-hp Le Rhone 9J engine. No further details are known.

Macchi M.14 single-seat fighter with one 110-hp Le Rhone 9J engine

Wingspan 8.20 m; length, 5.65 m; height 2.62 m; wing area 16,60 sq m

Empty weight 440 kg; loaded weight 640 kg

Maximum speed 182 km/h; climb to 1,000 m in 3.5 minutes; endurance 2 hours.

Ten examples built

The M.14 single-seat sesquiplane fighter was designed by Alessandro Tonini. While certainly not a direct copy of the Hanriot HD.1s that Macchi had produced under license, it did bear an uncanny likeness of that machine. It was of all wood construction and had a Warren truss type interplane bracing. The engine was a 110-hp Le Rhone 9J nine-cylinder rotary. The armament was two synchronized 7,7-mm Vickers guns.

Technical

Wings - two spar wooden wing covered in fabric. Ailerons on the upper wing only. The wings had a marked dihedral on the upper wing, while the lower wings were straight. The “W” shaped struts (joined at the mid portion of the lower wing on each side, was later seen in other Italian fighter designs, most notably the CR.42.

Fuselage - similar to the HD.1. The fuselage sides were flat.

Power Plant - The engine was a 110-hp Le Rhone 9J rotary engine for the M.14 bis fighter and a 80-hp engine or the M.14 fighter trainer. The 90-hp version may have never been built.

Landing Gear - Landing gear with faired struts an additional fairing covering the landing gear strut. These struts were intended to act as an auxiliary airfoil.

Testing

Flight testing commenced in the spring of 1918, but the prototype was destroyed in June of that year when it crashed, killing Clemente Maggiora. Aircraft 20931 underwent evaluation in 1919 at Montecelio. By December 1919 there were seven M.14s at Montecelio. However, no additional orders were forthcoming. The M.14’s performance was considered satisfactory, but not notably superior to the other Italian fighters then in service. The ten M.14s were employed as advanced trainers; these carried serials 20931 to 20940. At least one (20935) appeared on the civil register carrying serial I-BADG.

Foreign Service

Spain - An example was purchased in Spain. According to the then Lieutenant Gomez Spencer, who flew the sole prototype at Getafe around 1922, it cost the Aeronautica Militar only 6,000 pesetas. It was equipped with a 110-hp Le Rhone 9J engine. No further details are known.

Macchi M.14 single-seat fighter with one 110-hp Le Rhone 9J engine

Wingspan 8.20 m; length, 5.65 m; height 2.62 m; wing area 16,60 sq m

Empty weight 440 kg; loaded weight 640 kg

Maximum speed 182 km/h; climb to 1,000 m in 3.5 minutes; endurance 2 hours.

Ten examples built

Macchi M.15

The two-seat reconnaissance Macchi M.15 was designed by Tonini and Bergonzi and appeared late in 1918.

Intended to be used as a high-speed reconnaissance aircraft over the battlefront, it was an unequal-span biplane with its pilot and observer seated close together in tandem open cockpits. The structure was mainly of wood and had the “W”-form Warren-truss style wing bracing, typical of Macchi aircraft. This arrangement provided additional strength. There was provision for three cameras and a radio transmitter, and armament comprised three 7.7-mm (0.303-in) machine-guns.

A modified version designated M.15bis appeared in 1922, which differed externally by having revised vertical tail surfaces.

The type equipped 115a Squadriglia da Ricognizione at Bologna from 1922 to 1924, but it is believed that not more than 20 examples of both versions were built. After being retired from service, a few M,15s were used for experimental purposes, including one used by the Prospero Freri for parachute testing.

Macchi M.15 two-seat reconnaisance aircraft with one 300-hp (224-kW) Fiat A.12bis engine

Wingspan 13.38 m; length 8.60 tn; height 3.30 m; wing area 42 sq m

Empty weight 1,125 kg; maximum take-off weight 1635 kg; payload 510 kg;

Maximum speed 200 km/h, service ceiling of 6,000 m, climb to 5,000 m in 50 minutes, range of 600 km, endurance 3 hours

The two-seat reconnaissance Macchi M.15 was designed by Tonini and Bergonzi and appeared late in 1918.

Intended to be used as a high-speed reconnaissance aircraft over the battlefront, it was an unequal-span biplane with its pilot and observer seated close together in tandem open cockpits. The structure was mainly of wood and had the “W”-form Warren-truss style wing bracing, typical of Macchi aircraft. This arrangement provided additional strength. There was provision for three cameras and a radio transmitter, and armament comprised three 7.7-mm (0.303-in) machine-guns.

A modified version designated M.15bis appeared in 1922, which differed externally by having revised vertical tail surfaces.

The type equipped 115a Squadriglia da Ricognizione at Bologna from 1922 to 1924, but it is believed that not more than 20 examples of both versions were built. After being retired from service, a few M,15s were used for experimental purposes, including one used by the Prospero Freri for parachute testing.

Macchi M.15 two-seat reconnaisance aircraft with one 300-hp (224-kW) Fiat A.12bis engine

Wingspan 13.38 m; length 8.60 tn; height 3.30 m; wing area 42 sq m

Empty weight 1,125 kg; maximum take-off weight 1635 kg; payload 510 kg;

Maximum speed 200 km/h, service ceiling of 6,000 m, climb to 5,000 m in 50 minutes, range of 600 km, endurance 3 hours

Macchi M.7, M.7bis, & M.7ter

The driving force behind the M.7 was the availability of the 250-hp Isotta Fraschini V6 that represented about a 33% increase over the 190-hp engine used on the M.5. Due to the use of a more powerful engine, a larger fuel tank was needed. Space for this new tank was created inside the M.7s airframe which resulted in the need to widen the fuselage.

It had a simplified wing cellule, inspired by the preceding M.6, with a single bay of splayed interplane struts. The span and chord of the upper wing was reduced, while the lower, two spar, wing had an increase in area. The Nieuport “V” struts were replaced by more conventional ones; Varriale believes that this was based on Macchi’s experience with building Hanriot HD.1s under license.

Originally, armament was to have been a single machine gun, but the prototype carried two. As with the M.5, the need for a high speed reconnaissance capability was catered to be designing a compartment with a retractable door which could carry a camera.

Technical

Fuselage - The hull was had an ash framework with a spruce skin, the fin being built integral with the hull.

Wings - The single bay wings were of unequal span with slight sweepback. Construction was built around ash spars with spruce ribs, covered in fabric. The single bay of struts were canted outwards. Ailerons were placed on the outer panels of the upper wing.

Tail - Similar structure to the wings with a wood structure covered in fabric. It was placed approximately 1/3 of the way up the fin and rudder and was braced by struts.

Floats - there were two stabilizing floats under the lower wing.

Engine - 247-hp Isotta-Fraschini V.6 engine mounted between the wings above the hull. It was supported by wooden “N” struts between the wings. The engine was mounted in a pusher configuration with a large radiator placed in front. There was a small oil cooler underneath the radiator.

Accommodation - the single pilot sat directly beneath the radiator. There was a small windshield and a faired headrest.

Armament - two Vickers 0.303 machine-guns mounted on the sides of the hull.

Production

1918

Testing of the M.7 prototype began in early 1918 at the Nieuport-Macchi seaplane facility at Schiranna, and tests were promising enough to result in a production contract for 1,085 aircraft. About a third of these were to come from Macchi, and the remainder to be built under license by five subcontractors.

Only 11 were delivered before the Armistice led to the cancellation of the contract.

By 1920 there were 10 still in service, but were still being used in the seaplane fighter units five years later.

Postwar

The M.7 earned a second chance postwar. Virtually all of the aircraft produced postwar would go to the Regia Aeronautica; foreign sales were minimal (see below).

In May 1923 Macchi received its final M.7 contract, covering 30 aircraft (serialled 24396-24425, including a pattern airframe for Piaggio) and bringing total M.7 production to about 142.

Camurati has reconstructed the Regia Aeronautica serial numbers and placed the number of M.7ter built at 154 machines: 109 from Macchi and 45 from Piaggio. Testing revealed that the performance of the Piaggio machines were inferior to those built by Macchi.

The M.7ter AR production included ten aircraft drawn from the batch 25410-25449. These were assigned to Taranto where 166a Squadriglia was formed in 1925.

Variants

The M.7 had only limited success in the foreign market. However, Macchi appears to have had considerable faith in the designs a number of variants were developed postwar. The firm’s foresight paid off, and over 100 variants of the M.7 were used by all the Squadriglie Caccia Marittima (Naval Fighter Squadrons) in the 1920s.

M.7 Racer - Five M.7s took part in the trials to select the Italian participants for the 1921 Schneider Trophy. As the contest was being held in Venice that year, Italy was determined to win. The five M.7s were flown by de Briganti, Buonsembiante, Corgnolino, Falaschi and de Sio. De Briganti and Corgnolino won places in the Italian team, Falaschi’s M.7 crashed before the trial began, and the other two were eliminated.

In the event that, due to the withdrawal (for various reasons) of the other countries involved, the M.7 had merely to fly the course to win the trophy. See entry for M.7 bis.

M.7bis - The M.7bis had wing span and area reduced to 25 ft 5 in (7,75 m) and 256.19 sq ft (23,80 m2) respectively. It was based on the modified M.7 had won the Schneider Trophy in August 1921 with an average speed of 117.75 mph (189,50 km/h).

The Macchi M.7bis would have the chance to prove itself against real competition in 1922s Schneider Trophy race. M.7bis I-BAFV had this opportunity handed to it, once again, by luck. The Italian aircraft chosen to race, the Savoia S.50, had crashed. The M.7bis came in fourth, and last, with an average speed of 199.607 km/h (124.029 mph).