В.Кондратьев Самолеты первой мировой войны

ДЕ ХЭВИЛЛЕНД DH.9 / DE HAVILLAND DH.9

Цельнодеревянный двухместный биплан с полотняной обшивкой. Развитие типа DH.4 с рядом нововведений. Пилотская кабина сдвинута назад, вплотную к кабине летнаба, а на ее прежнем месте установлен топливный бак. Применены крылья с лучшими несущими свойствами и выдвижной подфюзеляжный радиатор.

Заказ на серийную постройку машины был выдан в июле 1917-го, однако затянувшиеся проблемы с доводкой силовой установки привели к тому, что первые два дивизиона RAF, вооруженные DH.9, прибыли на фронт только в апреле следующего года. Вопреки ожиданиям, летные данные самолета оказались не лучше, чем у его предшественника. А появление у немцев истребителей нового поколения обусловило тяжелые потери среди экипажей "Де Хэвиллендов". Тем не менее в течение лета 1918-го DH.9 активно применялись на западном фронте, в Палестине, Македонии и Месопотамии в качестве разведчиков и легких бомбардировщиков. В разное время на них летало 12 дивизионов RAF. Из них два дивизиона входили в состав так называемых "Независимых воздушных сил", совершавших дальние рейды на стратегические объекты Германии. После неудачной бомбардировки города Майнц 31 июля 1918 года, когда из 12 машин 7 было сбито и еще у трех в полете отказали двигатели, DH.9 начали выводить из частей первой линии, заменяя их более современными DH.9A.

По окончании первой мировой войны часть самолетов, ранее действовавших против Турции в Закавказье, была передана белой армии. Кроме того, на помощь белому движению прибыли в Россию 47-й и 221-й дивизионы RAF, вооруженные "Кэмелами" и DH.9. Еще несколько десятков машин этого типа поступило в 1919 году в распоряжение генерала Деникина. Весной 1920 года 27 "Де Хэвиллендов", из них 25 DH.9, составляли основу ВВС крымской группировки белогвардейцев. Им принадлежит решающая роль в разгроме красного кавкорпуса Жлобы и отражении летнего наступления большевиков на Крым. Позднее врангелевские DH.9 участвовали в боях в Северной Таврии и на Каховском плацдарме. К началу ноября из-за сильного износа и отсутствия запчастей ни один из них уже не мог подняться в воздух.

Выпуск "девяток" продолжался и в послевоенные годы. 12 английских заводов построили в общем счете 3204 аппарата (частично - в гражданском исполнении). Кроме того около 500 машин с двигателями "Испано-Сюиза" было выпущено в 1920-х годах в Испании и 30 - в Бельгии. DH.9 английской постройки стояли на вооружении в Польше, Голландии, Эстонии, Швейцарии и Южной Африке.

ДВИГАТЕЛЬ

BHP ("Бердмор-Халфорд-Пуллинджер"), названный позже Сиддли "Пума", 230л.с.

ВООРУЖЕНИЕ

1 синхр. "Виккерс" и 2 "Льюиса" на турели "Скэрф", до 200 кг. бомб.

ЛЕТНО-ТЕХНИЧЕСКИЕ ХАРАКТЕРИСТИКИ

(D.H.9 1918г)

Размах, м 12,90

Длина, м 9,20

Высота, м 3,52

Площадь крыла, кв.м 40,40

Сухой вес, кг 1040

Взлетный вес, кг 1670

Двигатель: "Роллс-Ройс"

мощность, л. с. 360

Скорость максимальная, км/ч 179

Время набора высоты, м/мин 2000/11

Дальность полета, км 680

Потолок, м 4710

Экипаж, чел. 2

Вооружение 3 пулемета

310 кг бомб

Показать полностью

А.Шепс Самолеты Первой мировой войны. Страны Антанты

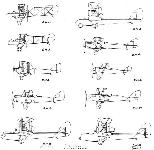

Де Хевилленд D.Н.9 1918 г.

Опыт эксплуатации в боевых частях самолетов D.H.4 потребовал значительной модернизации этих машин. После значительной доработки в дивизионы стали поступать новые машины D.Н.9.

Эти самолеты имели много общего со своим предшественником. Конструкция фюзеляжа, крыльев, оперения и шасси осталась практически такой же. Основные отличия были в конструкции кабины. Топливный бак располагался на D.Н.9 сразу за двигателем, а не между кабинами пилота и наблюдателя, как у D.Н.4. D.Н.9 имел более толстый профиль крыла, на этих машинах устанавливался более мощный двигатель Роллc-Ройс "Игл" мощностью 360 л. с. или "Либерти" (400 л. с.). На машинах устанавливался новый прицел, был увеличен боезапас пулеметов. Самолет мог нести 410 кг бомб.

Эта машина оказалась одним из самых лучших легких бомбардировщиков Первой мировой войны, самолет строился массовыми сериями в Великобритании и США.

Модификации

D.Н.9 - развитие самолетов серии D.Н.4, на этих машинах ставился двигатель Роллc-Ройс "Игл" мощностью 360 или 375 л. с. с двухлопастным винтом. На самолете устанавливалось 3 пулемета (2 синхронных пулемета "Виккерс" и 1 "Льюис" на турели).

Показать полностью

В.Шавров История конструкций самолетов в СССР до 1938 г.

Самолет Р-1 (DH-9) с двигателем "Даймлер" ("Мерседес") в 260 л. с. Самолет мало отличался от предыдущего (кроме расположения кабин). Было сделано около 100 экземпляров, в том числе несколько десятков из купленных в 1922 г. в Англии планеров самолетов. Самолет выпускался в 1922-1923 гг.

Самолет Р-2 (Р-II, DH-9) с двигателем "Сиддлей-Пума" в 220 л. с. По размерам, конструкции и внешнему виду самолет почти не отличался от предыдущего. Выпускался в 1923 г. применялся главным образом в школах и отрядах. В 1925 г. для первого большого перелета советских летчиков Москва-Пекин были выпущены под руководством инженера В. С. Денисова два таких самолета. На одном из них радиатор имел эллиптическую форму, на другом - спрямленные бока. Винты на обоих самолетах. были выполнены с небольшим коком. Летные данные этих самолетов несколько улучшились. В перелете участвовал только второй из них (летчик А. Н. Екатов).

Всего на авиазаводе № 1 было построено 130 самолетов Р-2.

Самолет||DH-9 (Р-1)/DH-9 (P-2)

Год выпуска||1922 /1923

Двигатель , марка||()/

мощность, л. с.||260 /220

Длина самолета, м||9,38/9,5

Размах крыла, м||12,94/12,94

Площадь крыла, м2||40,00/40

Масса пустого, кг||1200/1230

Масса топлива+ масла, кг||252/250

Масса полной нагрузки, кг||520/500

Полетная масса, кг||1720/1730

Удельная нагрузка на крыло, кг/м2||43,0/44,3

Удельная нагрузка на мощность, кг/лс||6,6/7,9

Весовая отдача,%||30,2/29

Скорость максимальная у земли, км/ч||170/165

Скорость посадочная, км/ч||95/80

Время набора высоты||

1000м, мин||6,5/7

2000м, мин||15/16

3000м, мин||28/30

Потолок практический, м||4580/4500

Продолжительность полета, ч.||4/4

Дальность полета, км||680/660

Разбег, м||?/250

Показать полностью

A.Jackson De Havilland Aircraft since 1909 (Putnam)

De Havilland D.H.9

By the summer of 1917 the need had become apparent for a fast bomber capable of carrying heavier loads over greater distances than the D.H.4. Reluctant to abandon altogether the manufacturing facilities developed for this successful and well proven type, the Air Board finally sanctioned the large scale production of a version so drastically modified that it was necessary to give it the new type number D.H.9. Structurally similar to its predecessor, the D.H.9 used identical mainplanes and tail surfaces but the pilot no longer sat in jeopardy between engine and fuel tanks, but next to, and in communication with, the gunner. The nose was of a better streamlined shape and the engine installation resembled that of the Fiat engined D.H.4, but with the added refinement of a radiator retracting into the underside of the front fuselage as a means of temperature control. The prototype was a D.H.4 numbered A7559, converted by the Aircraft Manufacturing Co. Ltd. and fitted with a 230 h.p. Galloway-built B.H.P. engine sometimes known as the Adriatic. Flight trials commenced at Hendon in July 1917 and contracts already awarded to sub-contractors were amended so that D.H.9s rolled from the production lines instead of D.H.4s.

Production machines, ultimately turned out at the rate of one every 40 minutes, were fitted initially with the Siddeley-built B.H.P. engine but the majority had the Siddeley Puma, a lightweight version of the B.H.P. modified for mass production by the Siddeley-Deasy Car Company. Teething troubles proved so serious that the Puma, although expected to deliver 300 h.p., had to be derated to 230 h.p., with the result that the D.H.9 was underpowered and consequently inferior in performance to the aircraft it was to replace. With full military load comprising 70 gallons of fuel, 4 1/2 gallons of oil, 6 1/2 gallons of water, one pilot's forward firing Vickers gun operated by Constantinesco interruptor gear, observer's Lewis gun, two 230 lb. or four 112 lb. bombs, it was unable to climb above 13,000 ft. Deliveries commenced with a batch of five at the end of 1917 and the type was in service with squadrons in France by April 1918. Inevitably serious losses were incurred such as on July 31. 1918 when only two out of twelve D.H.9s returned from a raid on Germany. The prevalence of engine trouble put an additional and intolerable burden on aircrews, and Nos. 99 and 104 Squadrons alone suffered 123 engine failures out of 848 sorties flown before the Armistice. The D.H.4 was therefore retained in service and the D.H.9 supplemented rather than superseded it. In less hotly contested areas, the D.H.9 enjoyed greater success, notably in September 1918 against the Turks in Palestine. Long range reconnaissance flights of over 300 miles were made against the Bulgars from bases in Macedonia, and ranges of over 400 miles were achieved by D.H.9s locally modified in the Aegean Islands to carry overload fuel tanks for the bombing of Constantinople.

At home the D.H.9 joined D.H.4s on coastal defence and anti-Zeppelin work, and at the end of the war replaced some of the D.H.6s on antisubmarine patrols. Thereafter the D.H.9 was relegated to non-combatant roles and on December 17, 1918 those of No. 99 Squadron, operating with D.H.4s of Nos. 55 and 57 Squadrons, inaugurated the first cross-Channel air mail service. Twenty five bags of mail for the Army of Occupation on the Rhine were flown to Valenciennes in bad weather, en route to Cologne. These squadrons made 917 sorties during the winter out of a possible 1,017. By July 1919 no D.H.9s remained on R.A.F. charge, the last examples in service being the ambulance versions operating with 'Z Force' in Somaliland. These, exemplified by D3117, carried one stretcher case in a coffin-like enclosure on top of the rear fuselage and had the upper trailing edge cut-out filled in.

Although the D.H.9 was not a success in its intended role and faded ignominiously from the R.A.F. after suffering rapid replacement by the D.H.9A, its career was by no means over. Many interesting modifications were made to it and after the experimental installation of 250 h.p. Fiat A-12 engines in D.H.9s C6052 and D5748, a batch of one hundred commencing D2776 was ordered from Short Brothers. As the engine closely resembled the Puma externally the main distinguishing feature was the exhaust manifold, fitted to the starboard side on Fiats and to the port side on Pumas, but in addition the radiator was fixed and equipped with vertical shutters because of the greater length of the Fiat installation. Some of this batch were later converted to Pumas for deck landing trials on H.M. Aircraft Carrier Eagle in 1921, and were fitted with D.H.4 type front radiators instead of the underslung type, to minimise damage if forced to ditch.

In February 1918 one of the prototype Napier Lion, broad arrow, 12 cylinder, watercooled engines was experimentally fitted at Farnborough to the D.H.9 C6078 and first flown on March 16th. The same machine was later fitted with a developed Lion engine and flown, on October 20th, to Martlesham where on January 2, 1919 Capt. Andrew Lang flew it to 30,500 ft. and established a World's altitude record. Throughout 1919 the R.A.E. experimented with an R.H.A. supercharger fitted to E630 and with alternative radiator positions on D2825.

The success of the Liberty engined D.H.4 prompted the American Expeditionary Force to install the improved 435 h.p. Liberty 12A engine in the D.H.9 and two airframes, one of which was C6058, were acquired for this purpose in July 1918.

After the war surplus D.H.9s took on a new lease of life in the service of other nations, mainly because their low initial cost was counted above military invincibility. Eighteen were supplied to Belgium, 12 to Poland, 48 to South Africa as part of the Imperial Gift, 9 to New Zealand, 28 to Australia and others to Canada, India, Afghanistan, Greece, the Irish Free State, Holland and Latvia. One of the 20 Puma engined D.H.9s supplied to Chile was flown by the Director of Civil Aviation, Capt. Aracena, 1,850 miles from Santiago to Rio de Janeiro in the autumn of 1922 and in the same year D.H.9s 16 and 77 (ex H9133) of the Estonian Air Squadron, made the long flight from Tallinn to Riga. Earlier, in January 1920, the D.H.9 30 (ex D660) crashed at Tallinn at the end of an historic flight from Helsinki with the first load of bank notes for the newly created Estonian Republic. Those of the South African Air Force gave sterling service for many years, and at least one, 159, was fitted with a 200 h.p. Wolseley Viper and unofficially named the D.H. Mantis. Six saw active service during the Boudelzvartz rebellion in 1922 and two piloted by Capts. C. J. Venter D.F.C. and H. C. Daniel M.C, D.F.C., which flew 1,000 miles from Pretoria to Cape Town in 9 hours 45 minutes on March 5, 1924, were the first aircraft to make the journey in the daylight hours of one day. Others, e.g. 101, were used in 1925 on an experimental air mail service between Cape Town and Durban, 450 lb. of payload being carried on each trip. In the following year comparative trials took place at Roberts Heights between D.H.9s fitted with the A.D.C. Nimbus, Armstrong Siddeley Jaguar and Bristol Jupiter engines. Final choice fell on the Jupiter and a number of S.A.A.F. D.H.9s, rebuilt as the D.H.9J M'pala I general purpose type with Jupiter VI or as the M'pala II for communications with Jupiter VIII and divided axle wide track oleo undercarriage, survived until 1937. The designation D.H.9J was also used for the Jaguar engine conversions made at Stag Lane (see page 136), a form of ambiguity also practised with D.H.50 variants.

The Puma D.H.9 made a most important contribution to aerodynamic research when, in 1920, Mr. (later Sir Frederick) Handley Page equipped a standard aircraft, H9140, with his newly invented leading edge slots. These were full span, auxiliary aerofoils permanently fixed along both mainplanes to give maximum lift, thereby increasing the wing area by 34 sq. ft. Later a taller undercarriage was fitted and in September 1920 comparative trials took place at Farnborough against a standard D.H.9 D5755. These showed a reduction in stalling speed from 51 to 44 1/2 m.p.h. and at a public demonstration at Cricklewood on October 21, 1921 Maj. E. L. Foot took full advantage of the ground angle imparted by the tall undercarriage by taking off in a three point attitude and going straight into a sensational angle of climb. The performance of this H.P. 17 led to an order for the H.P. 19 Hanley, similarly equipped.

Following Maj. Hereward de Havilland's tour through Spain in a Lion engined D.H.9 in 1919. a number of war surplus D.H.9 airframes were sold to the Spanish Government. These were erected by the Hispano-Suiza company and fitted with 300 h.p. Hispano-Suiza 8Fb engines. From 1925 Hispano built the type under licence and a total production in excess of 500 has been quoted. They were used in the African squadrons for reconnaissance and also at the Advanced Training School at Guadalajara. At the outbreak of the Civil War 25 were still in service in Spain, of which 21 went over to the Reds, and at least one, 34-18, was still active in 1940.

D.H.9s equipping the Netherlands Army Air Service were unique, not only because they included 10 built at Stag Lane in 1922 from unused components and others impressed after they forced landed on neutral Dutch territory during the First World War, but because many were rejuvenated as late as 1934 with Wright Whirlwind radial engines. Similar treatment was also applied to 13 modified D.H.9s which were built by the Netherlands East Indies Army workshops in 1926. These had plywood fuselages, revised ailerons, enlarged fin and rudder, large D.H.50-type nose radiators and extended exhaust pipes. Several Dutch machines were converted for the photo-reconnaissance role and others, equipped as ambulances, closely resembled those used in Somaliland in 1919.

A demand for surplus D.H.9s, reconditioned at Croydon by the Aircraft Disposal Co. Ltd. continued until 1924, but so great was their original stock that large numbers of unsold machines remained dismantled and neglected until burned in 1931. One D.H.9. in Independent Air Force colours, numbered F1258 survives in the French Musee de l'Air and is currently (1987) housed at Le Bourget. Another is displayed at the South African National War Museum near Johannesburg.

SPECIFICATION AND DATA

Manufacturers:

The Aircraft Manufacturing Co. Ltd., Hendon, London, N.W.9

The Alliance Aeroplane Co. Ltd., Cambridge Rd, Hammersmith, London, W.6.

F. W. Berwick and Co. Ltd., Park Royal, London, N.W.10

Cubitt Ltd., Croydon, Surrey

Mann, Egerton and Co. Ltd., Aylsham Road, Norwich, Norfolk

National Aircraft Factory No. 1, Waddon, Surrey

National Aircraft Factory No. 2, Heaton Chapel, near Stockport, Lanes.

Netherlands East Indies Army Workshops, Andir, Java.

Short Bros. (Rochesterand Bedford) Ltd., Rochester. Kent

The Vulcan Engineering and Motor Co. (1906) Ltd., Crossens, Lanes.

Waring and Gillow Ltd., Cambridge Road, Hammersmith, London, W.6

G. & J. Weir Ltd., Cathcart, Glasgow

Westland Aircraft Works, Yeovil, Somerset

Whitehead Aircraft Co. Ltd., Townshend Road, Richmond, Surrey

SABCA, Haren Airport, Brussels, Belgium

Hispano-Suiza S.A., Guadalajara, Spain

Power Plants:

One 230 h.p. B.H.P. (Galloway Adriatic)

One 230 h.p. Siddeley Puma

One 290 h.p. Siddeley Puma high compression

One 250 h.p. Fiat A-12

One 300 h.p. A.D.C. Nimbus

One 300 h.p. Hispano-Suiza 8Fb

One 430 h.p. Napier Lion

One 435 h.p. Liberty 12A

One 465 h.p. Wright Whirlwind R-975

(Mantis) One 200 h.p. Wolseley Viper

(M'pala I) One 450 h.p. Bristol Jupiter VI

(M'pala II) One 480 h.p. Bristol Jupiter VIII

Dimensions, Weights and Performances (without bomb load):

Puma Fiat Lion Liberty

Span 42ft. 4 5/8 in. 42ft. 4 5/8 in. 42ft. 4 5/8 in. 42 ft. 4 5/8 in.

Length 30 ft. 5 in. 30 ft. 0 in. 30ft. 9 1/2 in. 30 ft. 0 in.

Height 11ft. 3 1/2 in. 11 ft. 2 in. 11ft. 7 3/4 in. 11ft. 2 in.

Wing area 434 sq. ft. 434 sq. ft. 434 sq. ft. 434 sq. ft.

Tare weight 2,230 lb. 2,460 lb. 2,544 lb. -

All-up weight 3,325 lb. 3,600 lb. 3,667 lb. 4,645 lb.

Maximum speed 109.5 m.p.h.* 117.5 m.p.h.* 138 m.p.h.* 114 m.p.h.**

Initial climb 625 ft./min. 725 ft./min. 1,600 ft./min. -

Service ceiling 15,500 ft. 17,500 ft. 23,000 ft. -

Endurance 4 1/2 hours - 3 1/2 hours -

* At 10,000 ft. ** At ground level.

Показать полностью

F.Manson British Bomber Since 1914 (Putnam)

Airco D.H.9

The unexpected appearance by German bombers over London on 13 June 1917 sparked an immediate reaction by the Chief of the General Staff, Sir William Robertson, who forthrightly demanded a considerable and immediate increase in aircraft production - assumed to be fighters with which to bolster the air defences of the British Isles. Eight days later, however, this expansion of the air services was qualified when it was decided to increase the number of RFC squadrons from 108 to 200, the majority of the new units to be equipped with bombers. The initial understanding of this was that Britain was planning retaliation by establishing a new bombing force with which to strike at German cities.

This was not to be - at least in the short term - and the only direct action taken at the time of the German daylight raids was to withdraw a single fighter squadron from France to an aerodrome in Kent.

The real significance of the decision announced on 21 June was the implicit recognition, by the relative success of the first German raid, of the bomber as a potentially decisive weapon of war, whether it was to be used against the enemy in the field or in his home. An immediate and significant increase in the production of long-range heavy bombers would have been beyond the conceivable capacity o f British manufacturers. Instead, production orders were immediately issued for 700 extra Airco D.H.4s, an aircraft that was beginning to appear in service and, with some reservations, was spoken of highly by the RFC.

On 23 July the Air Board was given preliminary details of an improved development of the D.H.4, to be termed the D.H.9, in which the shortcomings of that aeroplane would be overcome while retaining 90 per cent of the original airframe. The principal alteration was to relocate the pilot further aft, so as to be closer to his observer/gunner, by moving the fuel tank forward from its former position between the two crew members to a position between the engine and the pilot. This change would at least be applauded by many D.H.4 crews and remove one weakness of the aircraft in combat.

The other major change was in the choice of the BHP engine, said at that time to be developing 300hp. Based on this power the D.H.9 was calculated to be capable of a speed of 112 mph at 10,000 feet, a performance considered adequate to match enemy fighters. With such a degree of commonality with the D.H.4, it was pointed out that factories already producing that aeroplane would lose only a few weeks' production when changing over to the D.H.9. As if to prove the point, Airco had converted a D.H.4, A7559, to become the prototype D.H.9, and this was living by the end of July.

Unfortunately, yet again a new British engine, which had attracted considerable Government support and public funding, encountered serious difficulties when efforts were made to introduce it into production. The BHP engine had been selected for the D.H.9 as it was already scheduled for mass production, for which responsibility had been vested in the Siddeley-Deasy Motor Car Company, with 2,000 engines already ordered. By July sufficient quantities of the engines' cast aluminium cylinder blocks were being delivered to enable Siddeley-Deasy to produce 100 complete engines each month - until it was discovered that 90 per cent of the blocks were defective. A quick assessment of the cause and rectification of the fault proved impossible, and the decision to de-rate production BHP engines to 230hp was taken on the assumption that lower engine stresses would prevent the fault from causing engine failure, and so as not to delay deliveries to the Service. The assumption was badly flawed.

The first deliveries were made in November 1917 to No 108 Squadron, the first of the squadrons newly formed to fly the D.H.9 and then stationed at Stonehenge. Owing to the inevitable trouble with its engines, this Squadron did not move to France until July the following year. No 103 Squadron took delivery of its D.H.9s at nearby Old Sarum in December, and moved to France five months later.

D.H.9s were delivered to Nos 98 and 99 Squadrons, RFC, and Nos 2, 6 and 11 (Naval) Squadrons, RNAS, all in France during the first four months of 1918, followed by No 27 Squadron, RFC, shortly afterwards. By June nine squadrons were flying D.H.9s over the Western Front, and thirteen others were working up on them in the United Kingdom. All this, despite the fact that Maj-Gen Hugh Trenchard had learned in November 1917 that the performance of the D.H.9 was inferior to that of the D.H.4, which it was intended to replace. And on 14 November Sir Douglas Haig, influenced by Trenchard's dissatisfaction, expressed the view that the D.H.9 would be wholly outclassed as a day bomber by June 1918.

In action the D.H.9 fared disastrously, combat loss figures being doubled by losses due to engine failures. For instance, between May and November 1918, Nos 99 and 104 Squadrons (flying with the VIII Brigade) between them flew 848 aircraft sorties in the course of 83 bombing raids; 123 aircraft were forced to return with engine trouble, 54 aircraft were lost to enemy action, and 94 were destroyed in accidents. In a raid by twelve D.H.9s of No 99 Squadron against Mainz on 31 July, three aircraft turned back with engine trouble and seven others were shot down by German fighters; only the leader, Capt A H Taylor and one other pilot brought their machines back to their aerodrome at Azelot. During another raid by 21 D.H.9s of Nos 27 and 98 Squadrons against Aulnoye on 1st October, no fewer than fifteen turned back with engine trouble; the remainder turned back as they were unable to defend themselves with such depleted numbers.

The increasing scale of D.H.9 service in the face of heavy losses on the Western Front was the outcome of political intransigence by politicians, and Staffs' determination to pursue a policy that was demonstrably wrong, being afraid of the consequences if they changed course.

No one denied that the D.H.9 could have been an excellent bombing aircraft had the right engine been decided upon in the first place. Various alternatives were tried, including the six-cylinder, in-line Fiat A-12, of which Sir William Weir, Controller of Aeronautical Supplies on the Air Board, had ordered 2,000 examples for delivery between January and June 1918, but only 100 Fiat D.H.9s were produced (by Short Bros). Other engines flown experimental in the aircraft included a 290hp high compression version of the Siddeley Puma, and the 430hp Napier Lion (an aircraft which possessed a maximum speed of 144 mph at sea level without bombs). Another engine flown experimentally in the USA was the new Liberty 12, an engine that opened a new and more auspicious chapter in the history of the D.H.9, that of the D.H.9A.

It transpired that most of the D.H.9 squadrons which were formed in Britain during the spring and summer of 1918 were not destined to go to France; instead the aircraft began assuming the duty of coastal patrol off the British coasts. In doing so, they took over from another Airco aircraft, the D.H.6. This biplane was designed at the outset as a trainer but, with the increasing toll of shipping being taken by German submarines in 1917, they were adapted to carry a single 100 lb anti-submarine bomb, and equipped about 30 Flights distributed among a dozen coastal aerodromes. (In the Second World War, during the months when a German invasion threatened, a few de Havilland Tiger Moths were adapted to carry light bombs for 'anti-invasion' patrols off the coasts of Britain.)

D.H.9s gave valuable service in Palestine with sustained attacks on the retreating Turks during Allenby's offensive in the closing months of the War. Other D.H.9s, based in the Aegean, made attempts to bomb Constantinople, flights which took the aircraft to the limit of their endurance - even when carrying locally-made extra fuel tanks. Limited bombing raids were flown by No 47 Squadron, based in Macedonia, including attacks on retreating Bulgarian troops during September 1918.

A total of 3,204 D.H.9s had been built by the end of 1918, of which 2,166 had been delivered to the RFC, RNAS and RAF. Production even continued into 1919, with most of the postwar examples being delivered into storage, and most of them scrapped without ever being flown. A few remained in service until 1920, but by then the D.H.9A was equipping the peacetime Service.

Type: Single-engine, two-seat, two-bay biplane light bomber.

Manufacturers: The Aircraft Manufacturing Co Ltd, Hendon, London NW9; The Alliance Aeroplane Co Ltd, Hammersmith, London W6; F W Berwick & Co Ltd, Park Royal, London NW10; Cubitt Ltd, Croydon, Surrey; Mann, Egerton & Co Ltd, Aircraft Works, Norwich, Norfolk; National Aircraft Factory No 1, Waddon, Surrey; National Aircraft Factory No 2, Heaton Chapel, Lancashire; Short Bros (Rochester and Bedford) Ltd, Rochester, Kent; The Vulcan Motor and Engineering Co (1906) Ltd, Crossens, Lancashire; Waring and Gillow Ltd, Hammersmith, London W6; G & J Weir Ltd, Cathcart, Glasgow; Westland Aircraft Works, Yeovil, Somerset; Whitehead Aircraft Co Ltd, Richmond, Surrey.

Powerplant: One 230hp Galloway Adriatic (BHP) six-cylinder inline water-cooled engine driving two-blade wooden propeller; also 230hp Siddeley Puma (and 290hp high compression version), 230hp Fiat A-12; 430hp Napier Lion.

Structure: Wire-braced wooden structure, fabric- and ply-covered; two spruce wing spars, wooden V-strut undercarriage with rubber cord-sprung wheel axle.

Dimensions (Puma engine): Span, 42ft 4 3/8in; length, 30ft 5in; height, 11ft 3 1/2in; wing area, 434 sq ft.

Weights (Puma engine): Tare, 2,230 lb; all-up (460 lb bomb load), 3,790 lb.

Performance (Puma engine): Max speed, 113 mph at sea level, 109.5 mph at 10,000ft; climb to 10,000ft, 18 min 30 sec; service ceiling, 15,500ft; endurance, 4 1/2 hr.

Armament: Bomb load of up to 460 lb, comprising combinations of 230 lb and 112 lb bombs on external racks. Gun armament comprised one synchronized 0.303in Vickers machine gun on nose decking, offset to port, and either one or two Lewis guns with Scarff ring on observer's cockpit.

Prototype: One, A7559 (a converted D.H.4), first flown by Capt Geoffrey de Havilland at Hendon in July 1917.

Production: Total number of D.H.9s ordered, 4,630; total number built, 4,091. Westland, 300 (B7581-B7680, D7201-D7300 and F1767-F1866); Vulcan, 100 (B9331-B9430); Weir, 400 (C1151-C1450 and D9800-D9899); Berwick, 180 (C2151-C2230 and D7301-D7400); Airco, 1,200 (C6051-C6121, C6123-C6349, D2876-D3275, E5435, E5436, E8857-E9056 and H9113-119412); Cubitt, 500 (D451-D950); National Aircraft Factory No 2, 500 (D1001-D1500); Mann, Egerton, 100 (D1651-D1750); Short Bros, 100 (D2776-D2875); Waring and Gillow, 500 (D5551-D5850 [50 sub-contracted] and F1101-F1300); Whitehead, 100 (E601-E700); National Aircraft Factory No 1, 300 (F1-F300); Alliance, 350 (H5541-H5890). Of these 539 were cancelled, and approximately 800 were only partly completed or were delivered into storage from late-1918 onwards.

Summary of Service with RFC, RNAS and RAF: D.H.9s served with Nos 27,49,98, 99, 103, 104, 107, 108 and 110 Squadrons, RFC, on the Western Front; with Nos 17 and 47 Squadrons, RFC, in Macedonia; with No 105 Squadron, RAF, in Ireland; with Nos 117, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 132 and 137 Squadrons, RFC and/or RAF, based in the United Kingdom; with Nos 55, 142 and 144 Squadron in the Middle East; with Nos 202, 206, 211 and 218 Squadron, RAF, ex-RNAS, on the Western Front; with Nos 212, 219, 233, 250, 254 and 273 Squadrons, RAF, home based on coastal patrol; with Nos 55 and 142 Squadrons, RAF, in the Middle East (postwar); No 221 Squadron in the Aegean, on anti-submarine patrol and bombing; No 223 Squadron in the Aegean as light bomber unit; Nos 224, 226 and 227 Squadrons, RAF, in the Mediterranean as light bomber units; with No 269 Squadron, RAF, based in Egypt for coastal patrol; and with No 186 (Training) Squadron.

Показать полностью

P.Lewis British Bomber since 1914 (Putnam)

By the autumn of 1916, British defence successes against raiding Zeppelins had forced the Germans to reconsider the ultimate value of such attacks. The conclusion was that the evolution of the aeroplane in its diverse forms had forged ahead of the lighter-than-air weapon, thereby steadily reducing the airship’s potency, and that bombing of the United Kingdom by strong forces of bomber aircraft was the next logical and potentially effective step.

On 25th May, 1917, heavy German raids were made in daylight on towns in Kent, and again on 5th June when both Kent and Essex were bombed. On 13th June, 1917, a formation of Gothas dropped their lethal loads on London at midday, and another attack took place against the capital three weeks later on 7th July. An immediate revision of the country’s defence system was effected.

Another swift reaction to these attacks was a demand for a rapid increase in the number and the quality of British bombers. Large orders were placed for the successful D.H.4 and, at the same time, plans were drawn up for a successor - the D.H.9. The promise inherent in the D.H.9 was such that it was decided to order it in place of the D.H.4s for which contracts had just been let. A D.H.4 - A7559 - was immediately taken into the shops at Hendon and modified so as to become the prototype D.H.9. In its new guise A7559 made its first flight at Hendon in July, 1917, powered by the 230 h.p. B.H.P.

In most respects the new machine was identical with its predecessor, the main exterior differences being the new shape of nose, with the exposed cylinders of the engine, the retractable radiator on the underside of the fuselage just ahead of the undercarriage, and the alteration of the pilot’s cockpit to a rear position adjacent to the gunner. This new location of the pilot’s position removed two of the main adverse criticisms of the D.H.4 namely the inordinate distance between the cockpits, resulting in poor communication, and also the placing of the pilot between the main fuel tank and the engine - a situation far removed from any pilot’s liking.

Nevertheless, in spite of the promise at first displayed by the D.H.9, the programme ran into trouble through selection of the B.H.P. engine, with which unit the machine was unable to equal the performance of the illustrious Rolls-Royce-powered D.H.4. Notwithstanding, plans for the production of the B.H.P.-powered D.H.9 were too far advanced by the time that the unfortunate facts were known for any further alteration in engine selection and, by the end of 1917, the first production examples had been completed. The main obstacle in the way of success for the D.H.9 was its lack of performance at higher altitudes. It was incapable of carrying its bomb load at a steady 15,000 ft. and often was unable to exceed 13,000 ft. altitude. To reach its target, therefore, the D.H.9 had, perforce, to fight its way through enemy fighters, which found little difficulty in reaching the bombers’ operational level and thereafter conducting affairs to a great extent their own way.

The D.H.9 went into action during the spring of 1918, working particularly as part of the Independent Force. Persistent engine failure contributed its share to the troubles of the D.H.9 squadrons on the Western Front, and losses during the summer of 1918 were such that cogent doubts eventually arose about the type’s status as a first-line aircraft. Attempts to improve the performance of the D.H.9 by testing airframes fitted with alternative engines, among them the 230 h.p. and 290 h.p. Siddeley Puma, the 250 h.p. Fiat A-12 and the 430 h.p. Napier Lion, fared badly, little progress being made in bestowing a worthwhile performance on the machine, the experimental Lion installation turning out to be the most rewarding.

Показать полностью

J.Bruce British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 (Putnam)

de Havilland 9

ON June 13th, 1917, German bombers attacked London in daylight and inflicted casualties which exceeded those caused within the County of London by all the Zeppelin attacks made up to that time. A few hours after the raid, Sir William Robertson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, asked for a substantial increase in the number of British aeroplanes. The German raid was proof enough of the potentiality of the aeroplane as a weapon of offence, and of the need for adequate means of defence; and the Cabinet agreed with Sir William Robertson that more British aircraft were urgently needed.

At a meeting held at the War Office on June 21st, 1917, it was decided to increase the service squadrons of the R.F.C. from 108 to 200; the majority of the new squadrons were to be equipped with bombing aircraft. Seven hundred D.H.4s were ordered at the end of June, 1917, for the equipment of the new bombing squadrons, and Sir Douglas Haig was told that development of a machine with longer range than the D.H.4 would be undertaken in order to permit the ultimate extension of the area of bombing operations.

On July 23rd, 1917, the Controller of Technical Design laid before the Air Board plans of an extensively modified version of the D.H.4 which, it was claimed, would have a speed of 112 m.p.h. at 10,000 feet and a greater range. The modifications were so extensive that the machine had to be regarded as a new type, and was given the type number D.H.9. The Air Board did not immediately decide to abandon the well-tried D.H.4, but, at their next meeting three days later, an assurance was given that the adoption of the new design would delay production by no more than three or four weeks. It was therefore decided to substitute the D.H.9 for the D.H.4 in the contracts which had already been let with contractors.

The prototype D.H.9 was A.7559, a modified D.H.4, and was flying in July, 1917. The engine was the 230 h.p. Galloway-built B.H.P., sometimes referred to as the Galloway Adriatic. This was the B.H.P. engine in its original form. The official choice fell upon the B.H.P. engine for the D.H.9’s power plant because it had been selected for very large scale production. Mass production of the 230 h.p. B.H.P. engine was made the special responsibility of the Siddeley-Deasy Car Co., who were then building some twenty-five to thirty standard B.H.P.s per week. Two thousand engines were ordered from Siddeley-Deasy. Delays occurred before modifications could be made to facilitate quantity production, and a major difficulty arose from the production of the aluminium cylinder blocks. Enough cylinder blocks were available by July, 1917, to permit production of the engines at the rate of too per month, but it was soon found that more than 90 per cent of the cylinder blocks were defective. The modified engine had been named the Siddeley Puma and the first few were rated at 300 h.p., but these gave so much trouble owing to faulty cylinder blocks that the engine was de-rated to 230 h.p. Perhaps the original output of 300 h.p. was responsible for the first optimistic estimates of the D.H.9’s performance.

That these estimates would not be realised was known before the D.H.9 came into service. This information reached Major-General H. M. Trenchard in November, 1917, and on the 16th of that month he wrote to Major-General J. M. Salmond, then Director-General of Military Aeronautics, to say that he had learned unofficially from Mr Geoffrey de Havilland that the performance of the D.H.9 would be poorer than that of the Rolls-Royce-powered D.H.4, and that the new machine would be unable to reach 15,000 feet fully loaded. Major-General Trenchard went on: “I do not know who is responsible for deciding upon the D.H.9, but I should have thought that no-one would imagine we should be able to carry out long-distance bombing raids by day next year with machines inferior in performance to those we use for this purpose at present. I consider the situation critical. ... I am strongly of opinion that unless something is done at once we shall be in a very serious situation next year. ...” Major-General Salmond placed these representations before the Air Board, but was informed by Sir William Weir that the choice was between the B.H.P.-powered D.H.9 or nothing at all.

On November 14th Sir Douglas Haig, inspired by Major-General Trenchard, had asked for orders for D.H.9s to be reduced to limit their use to no more than fifteen squadrons, because the type would be outclassed as a day bomber by June, 1918.

But it was too late. As with the B.E.2c and 2e earlier in the war, the official decision had been taken to standardise the D.H.9, and production was too far advanced for a change to be made. Ultimately, production of the Siddeley Puma engine reached 200 per week, and D.H.9s were turned out at the rate of one every forty minutes.

The squadrons who had to fly the type had to make the best of a bad job, and there was a world of truth in the wry description of the D.H.9 as a “D.H.4. which has been officially interfered with in order to be suitable for mass-production and the B.H.P. motor”.

In construction the D.H.9 was identical to the D.H.4: indeed, the wings and tail unit were the same in every respect. The most obvious external differences between the D.H.9 and D.H.4 lay in the engine installation and the disposition of the cockpits. The later machine made a breakaway from contemporary British practice by having a retractable radiator placed under the fuselage instead of arranged round the airscrew shaft. The cowling of the engine gave the nose of the D.H.9 a “Hunnish” appearance, but the cylinders and exhaust manifold formed an inelegant excrescence. The revised cockpit arrangement was probably the only improvement over the D.H.4: pilot and observer were close together and were able to communicate instantly and easily with each other. The pilot was also spared the unenviable position he occupied in the D.H.4, between the engine and fuel tanks. Nevertheless, the farther aft position of the pilot gave rise to criticism because the forward and downward view was obscured by the lower wing. To improve matters a cut-out was made in the root of the lower starboard wing between the spars. The D.H.9’s gravity fuel tank was contained in the centre-section, between the spars.

The D.H.9 was, in short, a good aeroplane spoiled by a bad engine which, if the truth be told, was obsolete at the time it was adopted as the power unit. With the B.H.P. engine the D.H.9 was expected to lift a greater load than the more powerful D.H.4, and in doing so its ceiling and performance suffered so severely that it was an easy victim for the German fighting scouts, particularly when engine failure on several machines reduced the numbers of a formation and robbed it of some of its defensive fire-power. The D.H.9 was unable to maintain its height with full load at 15,000 feet, and was seldom able to fly above 13,000 feet. It was therefore at a severe tactical disadvantage.

The first production D.H.9s were completed late in 1917: five were delivered before the end of the year. The early machines had B.H.P. engines built by both the Galloway and Siddeley-Deasy concerns. The type was issued to the squadrons early in 1918. The first D.H.9s in France were those of Squadrons Nos. 98, 206 and 211, all of which were in France at the beginning of April, 1918. Nos. 98 and 206 were with the II Brigade, and participated in the Battle of the Lys. On April 12th, nineteen pilots of No. 206 Squadron flew a total of 76 hours, and on that day No. 98 mounted no less than six sorties.

The name of the D.H.9, like that of the Handley Page O/400, will probably be forever linked with that of the Independent Force. In May, 1918, Squadrons Nos. 99 and 104 joined the VIII Brigade, the forerunner of the Independent Force: No. 99 arrived in France on May 3rd, No. 104 on May 19th. The squadrons supplemented the work of the D.H.4s of No. 55 Squadron, and made their first raids on May 21 st and June 8th respectively. These two units carried out eighty-three raids before the Armistice. That total represented 848 machine-sorties: of these, no fewer than 123 had to return with engine trouble. During the period, No. 99 Squadron lost twenty-one D.H.9s and 104 Squadron thirty-three to enemy action, and a further ninety-four machines were otherwise wrecked.

The D.H.9’s operational showing did nothing to enhance Major-General Trenchard’s opinion of it. His prophecy that the machine would be outclassed by June, 1918, was soon fulfilled; and writing in that month he said it was imperative that every effort should be made to replace the D.H.9 by tbe Liberty-powered D.H.9A. By the end of August, 1918, Major-General Trenchard decided that the D.H.9 could no longer be regarded as a front-line type: the losses which must be expected from the continued use of the type did not justify sending the D.H.9 squadrons over the lines.

In his report on the work of the R.A.F. on the Western Front during October, 1918, Major-General J. M. Salmond said of the D.H.9 "... although this type of aeroplane has sufficient petrol, and oil, to enable it to reach objectives too miles from the lines, its low ceiling and inferior performance oblige it to accept battle when, and where, the defending forces choose, with the practical result that raids tend to become restricted to those areas within which protection can be afforded by the daily offensive patrols of scout squadrons....”

Of the melancholy events which inspired Major-General Salmond’s report, none was worse than the experience of No. 99 Squadron on July 31st, 1918. Twelve D.H.9s of the squadron set out at 5.30 a.m. that morning to attack Mainz but, true to form, engine trouble forced three of the formation to return. Over Saaralbe, enemy scouts attacked and shot down one D.H.9, and a subsequent onslaught by about forty enemy machines near Saarbrucken shot down three more D.H.gs. The five survivors battled on as far as Saarbrucken and dropped their bombs on the railway station; but the enemy fighters maintained their attack and another D.H.9 crashed near the centre of the town. Two more fell on the homeward journey: only the leader, Captain A. H. Taylor, and one other pilot brought their D.H.9s back to No. 99’s aerodrome at Azelot.

The enemy did not escape scot free. Part of Captain Taylor’s report reads: “We also accounted for eight enemy scouts definitely known to have crashed. ... We lost seven machines. ... I recommend that we return and finish the job.” But the squadron had lost fourteen experienced officers, and was unable to resume its work until the replacements had been adequately trained in formation flying.

Despite Major-General Trenchard’s decision of late August, the D.H.9 remained operational until the Armistice; indeed, so persistent were those in authority that it replaced the superior D.H.4 in several squadrons. Until the end, however, the D.H.4 was treated with greater respect than the D.H.9 by the enemy fighters. To the last, the D.H.9s were let down by their engines: on October 1st, 1918, of twenty-nine D.H.9s sent by Nos. 27 and 98 Squadrons to bomb the railway junction at Aulnoye, no fewer than fifteen had to turn back with engine trouble, and the depleted formation was unable to attack its objective.

On other fronts D.H.9s played a rather more successful part in achieving victory. In Palestine, those of No. 144 Squadron took part in the sustained attacks on the retreating Turks, on September 19th, 1918, on the Tul Karm-Nablus road, and two days later in the Wadi el Far‘a. On September 23rd, the attacks made by the D.H.9s on Mafraq station and on enemy columns on the Es Salt-‘Amman road helped to hasten the defeat of the Turks.

In Macedonia, No. 47 Squadron received its first D.H.9 on August 2nd, 1918, and “A” Flight of that unit was completely equipped with the type by August 21st, 1918. No. 17 Squadron similarly received a Flight in September, and each squadron had six D.H.9s at the time of the Armistice. The new aircraft made long-range reconnaissances possible, and frequently carried out flights of 300 miles. Between September 1st and 29th, the D.H.9s of No. 47 Squadron flew a total of 315 1/2 hours. In this theatre of war the D.H.9 was, in fact, used more for reconnaissance work than for bombing, but on September 21st the D.H.9s participated in the attacks on the retreating Bulgarian army caught in the Kosturino Pass.

The D.H.9s operating from the Aegean islands made serious attempts to bomb Constantinople by night and day: the flight was one of about 440 miles and took some 5 1/2 hours. The machines were fitted with “home-made” extra fuel tanks which increased their endurance to 5 3/4 hours. Thus, the margin of safety was so narrow that many of the D.H.9s failed to reach their home aerodromes, and landings were perforce made elsewhere, occasionally in the sea.

Coastal aerodromes in the United Kingdom received the D.H.9 in 1918 for anti-Zeppelin work and for escorting the big flying boats. One of the D.H.9s from Great Yarmouth air station (No. 212 Squadron, R.A.F.) attacked the Zeppelin L.65 on the night of August 5th/6th, 1918. It did not succeed in destroying the airship, but was itself lost in mysterious circumstances. Towards the end of the war, D.H.9s began to replace D.H.6s for anti-submarine patrols.

Since the B.H.P. engine was so unreliable, it is regrettable that history does not tell more about the D.H.9s which had the 250 h.p. Fiat A-12 engine. Two thousand engines of this type had been ordered in August, 1917, at the instigation of Sir William Weir. The contract stipulated that deliveries were to be made between January and June, 1918, and it was intended to allocate 1,000 engines to America and to use the other thousand in D.H.9s. Only a tenth of that number were so used, however: early installations of the Fiat were made in the D.H.9s numbered C.6052 and D.5748, and 100 Fiat-powered machines (numbered D.2776-D.2785) were ordered from Short Brothers.

The Fiat A-12 was a six-cylinder in-line engine, and its similarity in configuration to the B.H.P. resulted in a generally similar installation. The Fiat could be distinguished by its exhaust manifold on the starboard side; that of the B.H.P. was on the port.

In October, 1918, a D.H.9 was tested with the high-compression version of the Siddeley Puma, which gave 290 h.p. This engine made no appreciable improvement in the aircraft’s performance, however.

In the summer of 1917 the firm of D. Napier & Son designed an aero-engine of unusual configuration: it was a twelve-cylinder engine with cylinders arranged in three groups of four, which were disposed in the form of a broad arrow. At first this engine was known as the Napier Triple-Four, and in September, 1917, the manufacturers envisaged a power output of 300 b.h.p. at 10,000 feet.

The new engine was named the Napier Lion, and early in 1918 one of the prototype Lions was installed in the D.H.9 numbered C.6078. Early trials at Farnborough showed that the heating of the induction system was inadequate. The application of hot-water jackets and lagging to the induction pipes, of water jackets to the carburettor throttles, and of exhaust-heated jackets to the air intakes, proved to be of little use.

Development proceeded and, after the initial difficulties had been overcome, it became evident that the Lion was an excellent engine and one which would have been of great benefit to the D.H.9. By June, 1918, the Lion-Nine was returning good performance figures, and shortly afterwards C.6078 was fitted with the first production Napier Lion engine. The airframe was strengthened in several ways: at the forward end of the fuselage additional three-ply webs were fitted and steel plates were applied to cross-members; at the tail the bottom longerons were reinforced by ash strips; the front spar of the tailplane was reinforced, and steel tube bracing struts were fitted; and thicker plywood was applied to the centresection. The retractable radiator was increased in size.

With this engine the D.H.9 at last had a worthwhile performance. It was delivered to Martlesham Heath for service trials at the beginning of October, 1918. While there the machine was flown by Captain Andrew Lang to a height of 30,500 feet, a new world’s record at the time. The climb was made on January 2nd, 1919, and occupied 66 minutes 15 seconds. Lang’s observer was Lieutenant Blowes.

The American Expeditionary Force bought two D.H.9s in July, 1918. These machines were delivered without engines, and were used to test the installation of the 400 h.p. Liberty 12-A engine in the airframe. One went to America, for it was intended to produce the type there, powered by the Liberty engine. The projected scale of American manufacture made even the highly creditable rate of British production look somewhat amateurish, for no fewer than 14,000 aircraft were ordered. In October, 1918, four D.H.9s were in service with the U.S. Naval Northern Bombing Group in France, but it is uncertain whether they were American-built machines. An American-designed development of the D.H.9 was built under the designation USD-9. Four USD-9s were delivered in August, 1918: two were built by Dayton-Wright and two by the Engineering Division of the Bureau of Aircraft Production. All contracts were cancelled after the Armistice.

In 1918 eighteen D.H.9s were supplied to the Belgian Flying Corps, presumably for use as day bombers.

The D.H.9 remained on active service with the R.A.F. after the Armistice. In Russia, Nos. 47 and 221 Squadrons were equipped with a mixture of D.H.9s and D.H.9As for service with Denikin’s White Army in 1919. So intense was the cold that water had to be boiled and oil heated before the radiators and sumps of the aircraft could be filled. One captured machine was operated by the Reds towards the end of the campaign.

After the war the D.H.9 was used for a few years by the R.A.F., but was withdrawn in favour of the superior D.H.9A. It took some time for the D.H.9s to be disposed of, but other nations took advantage of the low price at which the Aircraft Disposals Co. sold the discarded machines.

The D.H.9 did a vast amount of pioneering work in the field of commercial aviation, and several modified versions appeared in the post-war years. The type was used for experimental purposes with Handley Page slots and in Sir Alan Cobham’s early experiments in flight refuelling. Some of the Commonwealth countries used D.H.9s, and those of the South African Air Force survived until 1937 in a much modified form known as the Mpala, which was powered by a Bristol Jupiter radial engine.

SPECIFICATION

Manufacturers: The Aircraft Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Hendon, London, N.W.

Other Contractors: The Alliance Aeroplane Co., Ltd., Cambridge Road, Hammersmith, London; F. W. Berwick & Co., Ltd., Park Royal, London, N.W. 10; Cubitt, Ltd., Croydon; Mann, Egerton & Co., Ltd., Aircraft Works, Norwich; National Aircraft Factory No. 1, Waddon; National Aircraft Factory No. 2, Heaton Chapel, near Stockport; Short Brothers, Rochester, Kent; The Vulcan Motor & Engineering Co. (1906), Ltd., Crossens, Southport; Waring & Gillow, Ltd., Cambridge Road, Hammersmith, London (and Wells Aviation Co., Ltd., 30 Whitehead’s Grove, Chelsea, London, S.W.8, under sub-contract); G. & J. Weir, Ltd., Cathcart, Glasgow; Westland Aircraft Works, Yeovil, Somerset; Whitehead Aircraft Co., Ltd., Old Drill Hall, Townshend Road, Richmond.

Power: 230 h.p. B.H.P. (Galloway Adriatic); 230 h.p. Siddeley Puma; 290 h.p. Siddeley Puma (high compression) ; 250 h.p. Fiat A-12; 430 h.p. Napier Lion; 400 h.p. Liberty 12-A.

Dimensions: Span: 42 ft 4 5/8 in. Length (B.H.P. and Puma): 30 ft 6 in., (Lion) 30 ft 9 1/2 in., (Liberty) 30 ft. Height: 11 ft 2 in. (with Lion, 11 ft 7 3/4 in.). Chord: 5 ft 6 in. Gap: 5 ft 6 in. Stagger: 12 in. Dihedral: 3. Incidence: 3. Span of tail: 14 ft. Wheel track: 6 ft. Tyres: 750 X 125 mm. Airscrew diameter: four-bladed, 8 ft 9 in.; two-bladed, 9 ft 6 1/2 in.; Napier Lion, 11 ft.

Areas: Wings: upper 223 sq ft, lower 211 sq ft, total 434 sq ft. Ailerons: each 20-5 sq ft, total 82 sq ft. Tailplane: 38 sq ft. Elevators: 24 sq ft. Fin: 5-4 sq ft. Rudder: 13-7 sq ft.

Tankage: On the prototype D.H.9 (A.7559) fuel tanks were as follows: petrol: two tanks behind engine, 30 gallons each, one gravity tank in centre section 10 1/2 gallons; total 70 1/2 gallons. Oil: under sump (forced feed) 5 gallons. Water: 7 1/2 gallons. On production D.H.9s: petrol: two tanks behind engine, one of 34 gallons, the other of 28 gallons, one gravity tank 8 gallons; total 70 gallons. Oil: under engine crank-case (B.H.P.) 4 1/2 gallons, (Napier Lion) 7 gallons. Water: 6 1/2 gallons.

Armament: One fixed forward-firing Vickers machine-gun mounted on top of fuselage immediately to the left of the pilot’s windscreen and synchronised by Constantinesco G.C. Gear. Loading handle: Hyland Type B. The observer had either a single Lewis machine-gun or a double-yoked pair on a Scarff ring-mounting on the rear cockpit. Bomb racks were fitted under the fuselage and under each lower wing; the bomb release-gear was of the Gledhill type. The bomb load consisted of two 230-lb bombs, three or four 112-lb bombs, or an equivalent weight of smaller bombs.

Service Use: Western Front: R.A.F. Squadrons Nos. 27, 49, 98, 99, 103, 104, 107, 108, 202, 206, 211 and 218. Used by Belgian Flying Corps, and a few saw service with the U.S. Naval Northern Bombing Group. Sea Patrol: No. 212 Squadron, Great Yarmouth; No. 250 Squadron, Padstow; No. 273 Squadron (Flights at Govehithe and Westgate). Palestine: No. 144 Squadron. Macedonia: Nos. 17 and 47 Squadrons. Mediterranean: Nos. 224, 225, 226 and 227 Squadrons. Aegean: Nos. 220, 221, 222 and 223 Squadrons. Russia: No. 47 Squadron at Ekaterinodar, No. 221 at Petrovsk. Training: Air Observers’ Schools at Eastchurch, Manston and New Romney; School of Photography, Maps and Reconnaissance at Farnborough; Schools of Navigation and Bomb Dropping at Stonehenge, Andover and Thetford. Also used by No. 10 Training Depot Squadron, Harling Road; No. 31 Training Squadron, Wyton; and at Cranwell and Shoreham.

Production and Allocation: By the end of 1918, a total of 3,204 D.H.9s were built. Of these 2,166 were distributed to R.A.F. units before October 31st, 1918, as follows: to squadrons with the B.E.F., 789; to the Independent Force, 144; to the squadrons of the 5th Group (for naval cooperation), fifty-two; to the Middle East Brigade, ninety-two; to the Mediterranean, 133; to training units, 956. In addition, eighteen were supplied to the Belgian Flying Corps in 1918; and America bought two without engines in July, 1918. On October 31st, 1918, the R.A.F. had 1,866 D.H.9s on charge. In France, 334 were with the B.E.F., seventy-one with the Independent Force, and four with the 5th Group. Seven were in Egypt and Palestine, twenty-one at Salonika, and seventy-eight were at Mediterranean stations; 135 were on the way to Eastern stations. At home, 184 were at training units; thirty-seven were with squadrons mobilising; 424 were at various aerodromes; one was in use for anti-submarine patrol; twenty-four were at Aeroplane Repair Depots; forty-one were with the nth Group in Ireland; 186 were with contractors; and 319 were in store.

Serial Numbers:

Serial Nos. Contractor Contract No.

A.7559 Aircraft Manufacturing Co. Converted under A.S.21273/1/17, supplied under A.S.17569

B.7581-B.7680 Westland Aircraft A.S.17570

B.9331-B.9430 Vulcan Motor & Engineering Co. 87/A/1413

C.1151-C.1450 G. & J. Weir A.S.17570

C.2151-C.2230 Berwick & Co. 87/A/1185

C.6051-G.6121

C.6123-C.6349 Aircraft Manufacturing Co. A.S.17569

D.451-D.950 Cubitt A.S.26928

D.1001-D.1500 National Aircraft Factory No. 2 A.S.32754

D.1651-D.1750 Mann, Egerton A.S. 17994

D.2776-D.2875 Short Brothers (Fiat engines) A.S.34886

D.2876-D.3274 Aircraft Manufacturing Co. A.s.17569

D.5551-D.5850 Waring & Gillow (50 machines were built by Wells Aviation Co. under sub-contract) A.S.20391

D.7201-D.7300 Westland Aircraft A.S.42381

D.7301-D.7400 Berwick & Co. A.S.37725

D.9800-D.9899 G. & J. Weir A.s.41634

E.601-E.700 Whitehead Aircraft A.S.2341

E.5435-E-5436 Aircraft Manufacturing Co. A.s.17569

E.8857-E.9056 Aircraft Manufacturing Co. 35A/4I8/C.296

F.1-F.300 National Aircraft Factory No. 1 35A/409/C.297 (only 241 completed)

F.1101-F.1300 Waring & Gillow 35A/4I6/C.295

F.1767-F.1866 Westland Aircraft A.s.19174

Between and about

H.5546 and H.5738 Alliance Aeroplane Co. -

Between and about

H.9133 and H.9340 -

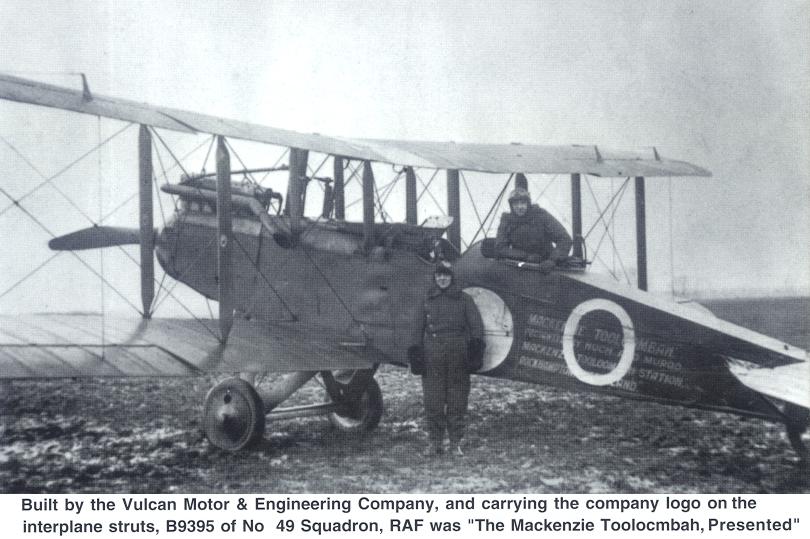

Notes on Individual Machines: Used by No. 49 Squadron: C.2202, C.6114, C.6116, C.6135, C.6175, D.457, D.461, D.3052, D.5576, D.5585, D.5596, E.623. Used by No. 98 Squadron: C.2221, C.6079, C.6106, C.6108, G.6119, D.3060, D.3169. Used by No. 103 Squadron: G.1213, C.2224, D.489, D.496, D.1003, D.2857, D.2866, D.3046. Used by No. 211 Squadron: B.7603, C.6270, D.2782, D.3233. Used at No. 1 School of Navigation and Bomb Dropping, Stonehenge: C.1320, C.2171, G.6128, D.1677, D.5681. Used at Manston: D.476, D.479, D.3028, D.5672. Other machines: A.7559: prototype D.H.9, fitted with Galloway-built B.H.P. engine No. 11, W.D.15434. B.9395: “The Mackenzie Tooloombah”. G.6051: Siddeley-built B.H.P. engine No. 5019, W.D.22693. C.6052: Fiat engine. G.6078: Napier Lion engine. D.3010 and D.3015: No. 186 Development Squadron, Gosport, 1919. D.5748: Fiat engine. D.5806: No. 186 Development Squadron, Gosport. E.8888: No. 186 Development Squadron, Gosport. F.1181: presented to Canada, February, 1919. F.1222: “Australia No. 26, Queensland No. 2, The Banchory”. F.1227: “Australia No. 27, Victoria No. 2, The Murroa”. F.1255: presented to Canada, February, 1919.

Costs:

Airframe without engine, instruments and guns £1,473 5s.

Siddeley Puma engine £1,089 0s.

Показать полностью

O.Thetford Aircraft of the Royal Air Force since 1918 (Putnam)

de Havilland DH 9 (Airco)

The immediate predecessor of the long-serving DH 9A, was the DH 9, a two-seat day bomber of which more than 3,000 were built for the RFC and RAF. In November 1918, DH 9s were still serving on Nos 17, 27, 47, 49, 98, 99, 103, 104, 107, 108, 119, 120, 144, 206, 211, 212, 218, 222, 223, 224, 226, 227, 250, 269 and 273 Squadrons of the RAF, with Nos 55, 221 and 270 in the process of re-equipping after the Armistice. The last DH 9s in service were those of No 55 Squadron in Egypt and Palestine, which were not withdrawn until September 1920. Powerplant: One 240hp BHP engine. Loaded weight, 3,669lb. Max speed, 111mph at 10,000ft; climb, 500ft/min; endurance, 4hr; service ceiling, 17,500ft.

Показать полностью

O.Thetford British Naval Aircraft since 1912 (Putnam)

de Havilland 9

With the exception of the B.E.2c, the D.H.9 was the most severely criticized British aeroplane of the First World War. It was designed as a replacement for the D.H.4 in day bomber squadrons, where it was intended to offer a much wider radius of action. In the event its performance fell far short of expectations, and it was actually inferior to the type it superseded. Although this fact was known before it entered service, it was decided (fantastic as it sounds) to proceed with large-scale production despite protests from commanders in the field. The inevitable results followed. Losses were high, one of the worst incidents being on 31 July 1918, when only two out of 12 D. H. 9s returned from a raid over Germany.

The fault lay not in the aeroplane but in the engine, the BHP, which failed to deliver its designed power of 300 hp and remained unreliable to the end. As a result, forced landings were common, and with full bomb-load the D.H.9 could rarely exceed 13,000 ft, leaving it at the mercy of enemy fighters.

The prototype (A7559) flew in July 1917 and production aircraft entered squadrons early in 1918. Although chiefly identified with the Independent Force, RAF, and the raids on Germany, the D.H.9 in fact saw a good deal of service on naval work of various kinds; with RNAS bombing squadrons in Belgium before they became RAF squadrons, on naval co-operation work in the Mediterranean and for anti-Zeppelin and anti-submarine patrols from coastal air stations in the United Kingdom. Some of these latter squadrons (technically RAF, but employed exclusively on maritime duties) retained D.H.9s as late as July 1919, when they disbanded.

During raids on Bruges Docks with the 5th Wing, RNAS, in March 1918, D.H.9s of No.6 Naval Squadron destroyed three cement barges, a submarine, two torpedo boats and a cargo vessel. This unit operated from Petite Synthe until transferred to the RAF on 1 April 1918.

UNITS ALLOCATED

Nos.2, 6 and 11 Naval Squadrons (later Nos.202, 206 and 211 Squadrons, RAF) in Belgium. Sea patrol: No.212 (Great Yarmouth). NO.219 (Manston). No.233 (Dover). No.236 (Mullion); No.250 (Padstow). No.254 (Prawle Point). No.260 (Westward Ho!), No.273 (Burgh Castle). Aegean: Nos.220. 221. 222 and 223. Mediterranean: Nos.224, 225, 226 and 227. Egypt: No.269 (Port Said) and NO.270 (Alexandria).

TECHNICAL DATA (D.H.9)

Description: Two-seat day bomber, also used for anti-submarine patrol. Wooden structure, fabric covered.

Manufacturers: Aircraft Manufacturing Co Ltd, Hendon, London, and fifteen sub-contractor .

Power Plant: One 230 hp BHP or Siddeley Puma.

Dimensions: Span, 42 ft 4 5/8 in. Length, 30 ft 6 in. Height, 11 ft 2 in. Wing area, 434 sq ft.

Weights: Empty, 2,203 lb. Loaded, 3,669 lb.

Peljormance: Maximum speed, 111 1/2 mph at 10,000 ft; 104 1/2 mph at 13,000 ft. Climb, 1 min 25 sec to 1 ,000 ft; 31 min 55 sec to 13,000 ft. Endurance, 4 1/2 hr. Service ceiling, 15,500 ft.

Armament: One fixed, synchronised Vickers machine-gun forward and either single or double free-mounted Lewis aft. Bomb-load: 460 lb.

Показать полностью

H.King Armament of British Aircraft (Putnam)

D.H.9. Scourged and derided though it was, the D.H.9 was more extensively employed than any aircraft of its class, both by the RFC and RAF. Such were the casualties inflicted by enemy fighters that formation flying was imperative. Being of an open kind this enabled the rear gun or guns to be worked effectively. The juxtaposition of the cockpits allowed not only better crew communication than in the D.H.4 but permitted internal bomb stowage also. Bombs could also be carried under each wing and under the fuselage.

The pilot's Vickers gun was located externally in a recess to port and with separate case and link chutes in the fuselage side. C.C. gear and a Hyland Type B loading handle were provided. The Scarff ring-mounting carried a Lewis gun, or occasionally two. Royal Air force Technical Notes for #de Havilland No.9' include these items under "Order of Erection":

'Connect all Engine Controls, Revolution Indicator, and C.C. Gear; Fit Fixed Bomb Cells and Fixed Bomb Release Gear; Fit Gun Mounting and Instrument Board; Fit Ammunition Box, Shutes, and Vickers Gun; Fit Scarff Ring Mounting; Place Movable Bomb Cells in position."

The external load of heavy bombs was typically two 230-lb or three or four 112-lb, but smaller bombs were also carried outside. With the D.H.9 the Gledhill bomb gear is mainly associated and an Air Ministry instruction dated March 1918 gave notice:

'Two sizes of this gear are being made at present. These will be issued as complete sets made up of the following units: (A) One fixed unit of two suspensions for 20 lb bombs. (This unit is a fixed part in the D.H.9.) (B) One movable unit of twelve suspensions for 20 lb bombs. (C) One movable unit of six suspensions for 50 lb bombs. (D) One operating mechanism and connection. Units B and C are interchangeable, and may be fitted in turn according to the type of bomb it is intended to carry. Units A. B. and C are placed in position immediately behind the engine and in front of the petrol tanks.

'In Units B and C the bomb rails carrying the slips, which are three in number, are mounted on the top of the bomb crates. The bomb crates are made of three ply wood and afford the lateral support needed by the bombs when stowed vertically. The crate in Unit B consists of 12 cells, made to fit the Cooper bomb, the crate in Unit C is similar in construction, with the exception that it is formed of six cells constructed to fit the 50 lb bombs.'

The bomb slips and release gear arc described thus:

'The slip is the mechanism on which the bomb is retained, and by means of which the bomb is released. It is self-locking, and consists of a lever carrying the suspension hook and a trigger lever, both of which are pivoted. The Cooper bomb is suspended from the suspension hook by a special wire loop which replaces the nut on the tail of the bomb. The 50 lb bomb is suspended by an eye bolt which forms an integral part of the nose fuse. The suspension hook receives the suspension lug of the bomb to be stowed, and is then automatically locked by a trigger lever, which projects through a slot in a sliding bar. When this bar is pulled, as is the case when operating the release, the end of this slot depresses a lever, and so allows the suspension hook to turn on its pivot and release the bomb.

'The pilot's release lever has seven positions, as follows: (1) Locked. (2) Free. (3) Release 2 Cooper bombs from fixed unit. (4) Release 3 Cooper bombs or 1-50-lb bomb. (5) Release 3 Cooper bombs or 2-50-lb bombs. (6) Release 3 Cooper bombs or 2-50-lb bombs. (7) Release 3 Cooper bombs or 1-50-lb bomb.'

The following instructions are given for loading:

'Place the release lever in "free" position and pull down the slides at the bottom of each bomb cell which hold the safety springs aside, push the suspension lug of the bomb upwards until a click is heard. The bomb will now be automatically held in position. When all the bombs are slowed, place the release handle in the locked position. The safely springs must now be adjusted by pushing up the slides which hold them aside while stowing the bombs is in progress."

The foregoing reference to one fixed unit of two suspensions for 20-lb bombs and one movable unit of twelve suspensions accords perfectly with one recorded test-load of fourteen 20-lb bombs.

Containers for Baby Incendiary Bombs were also carried internally, but the reported internal loads of two 230-lb or four 112-lb bombs must have been rare. Indeed, it is difficult to envisage the vertical stowage of 230-lb bombs which is stated to have been possible, for this type of bomb was 501 inches long, and this measurement, in addition to the length of the nose shackle and the depth of the suspension beam, would seem to be greater than the depth of the D.H.9 fuselage.

The bomb sight was of the Negative Lens type.

Показать полностью

L.Andersson Soviet Aircraft and Aviation 1917-1941 (Putnam)

De Havilland D.H. 4, D.H.9, R-1 and variants

Lacking resources for development of advanced and specialized aircraft the fledgling Soviet aviation industry copied what was at hand when production started again after the Civil War, a proven, reliable, versatile aircraft of simple construction - the de Havilland D.H.9 which later became known as the R-1 in the Soviet Union. Being used for reconnaissance, artillery observation, light bombing, attack, civil and military training, maritime patrol, seaplane training, liaison, target-towing, mail-carrying, experiments and in other roles, the R-1 was the Soviet aircraft of the 1920s. Nine different types of engines were installed in de Havilland and R-1 aircraft; Liberty, Siddeley Puma, Fiat, Rolls-Royce Eagle, Mercedes, M-5, Maybach, BMW and Lorraine-Dietrich, but the M-5-powered R-1s were the most numerous.

The D.H.9 was structurally similar to its predecessor and used identical wings and tail section, but the pilot's cockpit was moved back behind the fuel tanks and the forward part of the fuselage was better streamlined. A retractable radiator was fitted under the front fuselage. A D.H.4 was converted to the new standard and tested in July 1917, whereupon production immediately switched to the new model. Most of the D.H.9s were powered by the 230hp Siddeley Puma, but with this engine the new model was under-powered and, in fact, inferior in performance to the D.H.4 which it was to supplement rather than replace. The D.H.9A appeared in 1918. Developed by the Westland Aircraft company, it combined the 400hp Liberty engine and frontal radiator with the best features of the D.H.4 and D.H.9. The fuselage was strengthened by replacing the plywood partitions of the D.H.9 with wire cross bracing and wings of greater span were fitted to improve climb and ceiling.

After the war surplus D.H.9 and D.H.9A aircraft were reconditioned and exported, many by the Aircraft Disposal Company, or used for civil purposes and in the 1920s D.H.4, D.H.9 and D.H.9A aircraft served with the military air services of Arabia, Argentina (one only), Australia, Bolivia, Belgium, Canada, Cuba, Chile, Mexico, Estonia, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Holland, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Poland, Romania, Switzerland, Spain, South Africa, Turkey, the USA and the USSR.

By the end of 1920 nineteen captured Puma-engined D.H.9s and Liberty-engined D.H.9As were on charge. They were used mostly in the Ukraine and in Caucasia. More were repaired and put into service during the following year and by December 1921 forty-three were flying with RKKVF units. The authorities in Moscow had noted the reliability of the de Havilland types and when the opportunity arose to purchase more such aircraft from Britain there was no hesitation. The Secretary of the Royal Swedish Aero Club, Torsten Gullberg, who had been discussing an airline project with the Soviet Government offered to supply aircraft to the USSR in the spring of 1921. He contacted the Aircraft Disposal Company and began negotiations concerning reconditioned D.H.9s without engines. In Sweden he acquired 260hp Mercedes engines which had been smuggled out from Germany after the war and stored. A contract for forty aircraft and forty-eight engines was signed on 22 December 1921.

E I Gvaita went to England for inspection and acceptance of the aircraft. Four of the engines were sent to England and installed in each of the aircraft, which were then shipped from London to Leningrad on board the Swedish freighter Miranda. They arrived on 4 June 1922. The engines were shipped separately from Sweden. Anton Nilsson, another Swede who had joined the RKKVF as a pilot, was sent to Leningrad to supervise unloading of the consignments. These D.H.9s had the following s/ns: 1243, 1285, 2803, 5580, 5582, 5671, 5703, 5713, 5720, 5729, 5744-5746, 5748, 5752, 5758, 5778, 5786, 5795, 5800, 5803, 5805, 5808, 5811-5813, 5815, 5817, 5819, 5821, 5826-5828, 5832, 5841, 5846, 9152, 9165, 9334 and 9350 (most were almost certainly from the D and H serial batches). The first aircraft assembled by RVZ No. 1 and tested by Savin on 14 August was s/n 5817. Two aircraft (s/ns 5778 and 5813) were kept at the NOA.

One D.H.9A fitted with the 320hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engine was delivered in May 1922 for evaluation and in 1923 ten D.H.9As with 400hp Liberty and twenty D.H.9s with 220hp Puma engines were acquired from England via the Arcos Company. The Saturn arrived at Leningrad from London via Antwerp and Reval with seventeen of these aircraft in October 1923. Another four D.H.9As (Liberty engine) and twenty-two D.H.9s (Puma engine) followed in August 1924. In VVS documents the Rolls-Royce powered aircraft is identified as number 16105, but A J Jackson's De Havilland Aircraft since 1909 (Putnam, third edition, 1987) gives this aircraft as c/n 37. The ten D.H.9As were s/ ns 157 to 160, 2866, 2870, 3457, 3647, 3649, and 8802. The twenty D.H.9s were s/ns 138, 168, 206 to 213, 255, 468, 636, 1209, 5541, 5814, 9277, 9290, 9294 and 9329. The twenty-two D.H.9s delivered in 1924 were probably H5855, H5864, H5880, H9242, H9250, H9252, H9260, H9275, H9278, H9283, H9285, H9297, H9298, H9302, H9309, II9311, H9313, H9330, H9341 and H9309 which received British Cs of A in July 1924, and two others.

The British-built D.H.9s were used by the 1st Otdel'naya razvedivatel'naya aviaeskadril'ya at Ukhtomskaya, Moscow, the 2nd Otdel'naya razvedivatel'naya aviaeskadril'ya at Vitebsk and the 5th Otdel'nyi razvedivatel'nyi aviaotryad at Gomel' until 1924. One or two served with the 3rd, 6th, 10th, 13th and 14th Otdel'nye razvedivatel'nye aviaotryady in 1922-24, and later with the 17th and 83rd Aviaotryady and the 20th and 24th Aviaeskadrilii. The 4th Otdel'nyi razvedivatel'nyi aviaotryad at Tashkent received about ten in 1924 and used them into 1925, but four of these were flown to Kabul in October and handed over to the Afghanistan Government.

The Il'ich otryad, named after Lenin, whose middle name was Il'ich, was formed in April 1924 at Khar'kov. Twelve D.H.9As arrived in December 1923 and were assembled locally. Nine of these aircraft were handed over with ceremony by the ODVF on 18 May, 1924 and were followed by another four in June and July. They were given names including Donetskii shakhter, Krasnyi Kievlyanin, (Jkrainskii chekist, Shakhter Donhassa, Stalinskii proletarii, Profsoyuzy Ekaterinoslavshchiny, Samolet Sumshchiny, Yuzovskii proletarii, Chervonii vartovik podolii, Nezamoshnik Odesshchiny and Proletarii Odesshchiny (Donets Miner, Red Kiev Inhabitant, Ukrainian Cheka Officer, Miner of the Donbass, Stalin Proletarian, Trade-Unions of the Ekaterinoslav Region, Aircraft of the Sumy Area, Yuzovka Proletarian, Red Guard of Podol'e, Odessa Pauper, Odessa Pro-letarian). The D.H.9As of this unit were replaced, however, by Soviet- built R-ls before the end of the year.

The Mercedes-powered D.H.9s were withdrawn from use completely in 1925 and nineteen were handed over to Dobrolet along with forty-seven engines in 1927. Ten, and later one more, were assembled and the rest were reduced to spares. The Dobrolet D.H.9s did not receive normal civil registrations and had large white numbers painted on the fuselage sides instead, which were treated as registration numbers in the paperwork. After having been tested with little suc-cess as crop-dusters the civil D.H.9s were then assigned to photographic- work. Only three were actually sent on aerial photography missions in 1927 and one in 1928. All but four, which were re-registered CCCP-112 to CCCP-115, were then written off, the last example being cancelled in 1930. In 1928 the VVS offered Dobrolet twenty-eight additional D.H.9s, of which many were unserviceable, and a large number of extra wings, but the offer was refused.

Mercedes-engined D.H.9s used by Dobrolet

Reg Reg 1929 C/n In Service Notes

1 9152 2.27-6.29

2 CCCP-112 5826 4.27-29/30

3 1285 5.27-6.29 Crashed 11.28

4 2803 5.27-6.29

5 CCCP-113 5746 6.27-29/30

6 5778 7.27-6.29 Crashed 6.28

7 CCCP-114 5813 3.28-29/30

ДЛ-8 CCCP-115 9350 4.28-29/30

ДЛ-9 5821 3.28-6.29

ДЛ-10 5580 3.28-6.28 Crashed 22.6.28

ДЛ-11 5817 .29-29/30 Probably CCCP-116 ntu

In addition to service with the reconnaissance units, the Puma-engined D.H.9s and Liberty-engined D.H.9As were also used as trainers, before they were withdrawn from the reconnaissance units in 1924. They remained until 1928, most with the 1st Higher School of Military Pilots in Moscow, but some were flown at the 2nd School of Military Pilots, the Strel'bom school, the Military School of Special Service, the Military-Technical School, the 83rd Training Eskadril'ya and the Akademiya VVS. A few were also assigned to the NOA.

D.H.9 (D.H.9A), original aircraft

260hp Mercedes D.IVa (400hp Liberty 12)

Span 12.94 (14) m; length 9.38 (9.22) m; height (3.45) m; wing area 40 (45.22) m2