Книги

Putnam

P.Bowers

Curtiss Aircraft 1907-1947

150

P.Bowers - Curtiss Aircraft 1907-1947 /Putnam/

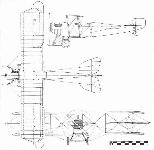

Bristol Fighter

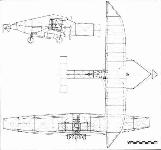

One of the successful European combat aeroplanes selected by the Bolling Commission for mass production in the United States was the Bristol F.2B, better known as the Bristol Fighter. The US government owned the rights to the design and assigned the official designation of USAO-l as an observation type, but the Bristol Fighter name stuck. This was to be Americanized to the extent of having parts dimensions altered to be compatible with standard American tooling and altering the front end to accommodate the new 400 hp Liberty engine in place of the original British Rolls-Royce Eagle. Curtiss was given a contract for 2,000 in October 1917.

Production lines were set up in the new Elmwood Plant m Buffalo, and the first Liberty-powered Bristol was ready for flight in April 1918. The Liberty engine installation was troublesome from the start. It was both too heavy and too powerful for the relatively standard Bristol airframe and there were cooling problems. Because of the size of the Liberty, the original neat nose radiator of the Bristol could not be used; several arrangements of side and belly radiators were tried as well as fixed and movable units in the upper wing centre section.

Following several serious crashes of early test models, the Curtiss contract was cancelled after 26 Bristols had been completed (US Army serial numbers 34232/34257). This did not kill off official US interest in the design, however. While Curtiss tried to develop its own version of a Bristol replacement, the CB, the Air Service Engmeenng Division at McCook Field developed lower-powered versions with 300 hp Wright-Hispano engines and new laminated wood monocoque fuselages. Thirty of these were eventually produced by the Dayton-Wright Aircraft Company under the designation of USXB-1A.

Bristol Fighter (USAO-1)

Observation aircraft. Pilot and observer/gunner.

400 hp Liberty.

Span 39 ft 4 in (11,98 m): length 27 ft 1 in (8,25 m); height 10 ft 2 in (3,09 m); wing area 416 sq ft (38,64 sq m).

Empty weight 2,245 lb (1.018,3 kg); gross weight 3,500 lb (1.587,57 kg).

Maximum speed 125 mph (201,16 km/h) at sea level: climb to 10,000 ft (3,048 m) 7,05 min; absolute ceiling 25,000 ft (7,620 m): endurance 2 hr.

Armament - two fixed Marlin and two flexible Lewis machine-guns.

One of the successful European combat aeroplanes selected by the Bolling Commission for mass production in the United States was the Bristol F.2B, better known as the Bristol Fighter. The US government owned the rights to the design and assigned the official designation of USAO-l as an observation type, but the Bristol Fighter name stuck. This was to be Americanized to the extent of having parts dimensions altered to be compatible with standard American tooling and altering the front end to accommodate the new 400 hp Liberty engine in place of the original British Rolls-Royce Eagle. Curtiss was given a contract for 2,000 in October 1917.

Production lines were set up in the new Elmwood Plant m Buffalo, and the first Liberty-powered Bristol was ready for flight in April 1918. The Liberty engine installation was troublesome from the start. It was both too heavy and too powerful for the relatively standard Bristol airframe and there were cooling problems. Because of the size of the Liberty, the original neat nose radiator of the Bristol could not be used; several arrangements of side and belly radiators were tried as well as fixed and movable units in the upper wing centre section.

Following several serious crashes of early test models, the Curtiss contract was cancelled after 26 Bristols had been completed (US Army serial numbers 34232/34257). This did not kill off official US interest in the design, however. While Curtiss tried to develop its own version of a Bristol replacement, the CB, the Air Service Engmeenng Division at McCook Field developed lower-powered versions with 300 hp Wright-Hispano engines and new laminated wood monocoque fuselages. Thirty of these were eventually produced by the Dayton-Wright Aircraft Company under the designation of USXB-1A.

Bristol Fighter (USAO-1)

Observation aircraft. Pilot and observer/gunner.

400 hp Liberty.

Span 39 ft 4 in (11,98 m): length 27 ft 1 in (8,25 m); height 10 ft 2 in (3,09 m); wing area 416 sq ft (38,64 sq m).

Empty weight 2,245 lb (1.018,3 kg); gross weight 3,500 lb (1.587,57 kg).

Maximum speed 125 mph (201,16 km/h) at sea level: climb to 10,000 ft (3,048 m) 7,05 min; absolute ceiling 25,000 ft (7,620 m): endurance 2 hr.

Armament - two fixed Marlin and two flexible Lewis machine-guns.

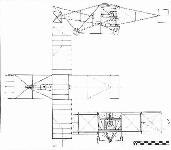

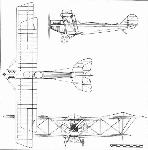

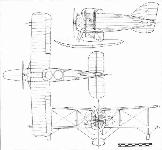

S.E.5

The S.E.5 was one of the leading British fighters of 1917 and was one of two European single-seaters chosen by the Bolling Commission for mass production in the United States. It was designed and built at the Royal Aircraft Factory and the letters stood for Scouting Experimental, Model 5. Powerplants were direct-drive and geared versions of the 180-200 hp French Hispano-Suiza and a British-built copy known as the Wolseley Viper.

Curtiss was given an order for 1,000 S.E.5s, but only one example was built (US Army serial 43153). Fifty-six others, sometimes referred to as Curtiss SE-5s, were British-built airframes sent to Curtiss for assembly. These were flown as trainers in the US under their original British serial numbers and markings. The single Curtiss-built SE-5, using the Americanized Hispano-Suiza engine as built by Wright-Martin, was delivered to the Army for test in September 1918, and was carried on Army books at a value of $544,716.

Additional British S.E.5s, delivered to American pursuit squadrons in France, were brought to the US when those squadrons returned home after the Armistice. These were first-line pursuit aircraft until replaced by new American designs in 1920. In 1923, fifty S.E.5s were sent to Eberhart Steel Products Company for rebuild as SE-5Es (for Wright E engine, the American-made 180 hp Hispano-Suiza) and served with other SE-5s as advanced trainers until 1927.

The S.E.5 was one of the leading British fighters of 1917 and was one of two European single-seaters chosen by the Bolling Commission for mass production in the United States. It was designed and built at the Royal Aircraft Factory and the letters stood for Scouting Experimental, Model 5. Powerplants were direct-drive and geared versions of the 180-200 hp French Hispano-Suiza and a British-built copy known as the Wolseley Viper.

Curtiss was given an order for 1,000 S.E.5s, but only one example was built (US Army serial 43153). Fifty-six others, sometimes referred to as Curtiss SE-5s, were British-built airframes sent to Curtiss for assembly. These were flown as trainers in the US under their original British serial numbers and markings. The single Curtiss-built SE-5, using the Americanized Hispano-Suiza engine as built by Wright-Martin, was delivered to the Army for test in September 1918, and was carried on Army books at a value of $544,716.

Additional British S.E.5s, delivered to American pursuit squadrons in France, were brought to the US when those squadrons returned home after the Armistice. These were first-line pursuit aircraft until replaced by new American designs in 1920. In 1923, fifty S.E.5s were sent to Eberhart Steel Products Company for rebuild as SE-5Es (for Wright E engine, the American-made 180 hp Hispano-Suiza) and served with other SE-5s as advanced trainers until 1927.

Curtiss completed only this one of 1,000 British S.E.5 fighters ordered but assembled 56 others that had been built in Britain.

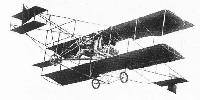

Aerodrome No.3, June Bug The June Bug, a further refinement of White Wing, was sponsored by Curtiss and was eminently successful with the same engine. First flown on 21 June, it made numerous flights, including a straightaway run of 1,140 yards (1,042 m) on the seventh flight. On 4 July, Curtiss made a pre-arranged flight to win the first task, or 'leg', of the Scientific American Trophy, which called for a straightaway flight of one kilometre (3,281 ft). After a couple of false starts, he won this with ease by flying over a mile (1.6 km) at a speed of 39 mph (62.76 km/h).

Span 42 ft 6 in (12,95 m); wing area 370 sq ft (34.37 sq m); gross weight 615 lb (279 kg).

Loon - In November 1908, the June Bug was put on twin wood-frame pontoons covered with cloth and was renamed Loon. Attempts to fly from the water were unsuccessful due to the high hydrodynamic drag of the pontoons.

Span 42 ft 6 in (12,95 m); wing area 370 sq ft (34.37 sq m); gross weight 615 lb (279 kg).

Loon - In November 1908, the June Bug was put on twin wood-frame pontoons covered with cloth and was renamed Loon. Attempts to fly from the water were unsuccessful due to the high hydrodynamic drag of the pontoons.

The AEA's third aircraft, the June Bug designed by Glenn Curtiss, won the Scientific American trophy for the first officially recorded flight of over a kilometre in the USA, accomplished by Curtiss on 4 July 1908.

A rare photograph of Glenn Curtiss' Loon (the June Bug on floats), which failed to become airborne during tests in 1908.

Aerodrome No.1, Red Wing The first AEA aeroplane was named Red Wing because of the colour of its fabric covering. It was a biplane with a movable elevator ahead of the wings and a fixed stabilizer behind. A movable rudder was provided, but no means of lateral control. Since it was to be flown from ice, it used skids for an undercarriage. The 'sponsor', or principal designer, was Lt Selfridge.

The first of two flights was made by Thomas Baldwin on 12 March, 1908, since Selfridge was absent on Army business. The flight covered a distance of 318 ft 11 in (97 m) and ended in a crash landing. This has been represented as the first public aeroplane flight in the United States, and figured in the subsequent controversies with the Wrights. The second flight, on 18 March, also ending in a crash, covered only 40 yards and proved the need for lateral control.

Span 43 ft 4 in (13.2 m); wing area 385 sq ft (35.76 sq m); gross weight 570 lb (258 kg); powerplant Curtiss 40 hp air-cooled V-8.

Aerodrome No.2, White Wing The second AEA aeroplane was White Wing, sponsored by Baldwin. It was very similar to Red Wing, except for the substitution of three wheels for the ice runners, and used the same engine. The most important innovation was the addition of movable lateral control surfaces on all four wingtips that later came to be called ailerons. In principle, these had the same effect as the Wright's wing-warping, but Curtiss claimed mechanical and control differences. The method of control reflected Curtiss's motorcyle experience - a yoke embraced the pilot's shoulders - when he wanted to bank for a turn, he leaned in the desired direction and the proper control movement was automatically applied.

White Wing made four flights, the first on 18 May, 1908, again with Baldwin at the controls. Distance was 93 yards (85 m) at a height of 10 ft (3 m). Longest flight was the third, at 339 yards (310m) with Curtiss flying. While Wing crashed on 23 May after McCurdy had flown 183 yards (167 m).

Span 42 ft 3 in (12.87 m); wing area 408 sq ft (37.9 sq m); gross weight 605 lb (274 kg).

The first of two flights was made by Thomas Baldwin on 12 March, 1908, since Selfridge was absent on Army business. The flight covered a distance of 318 ft 11 in (97 m) and ended in a crash landing. This has been represented as the first public aeroplane flight in the United States, and figured in the subsequent controversies with the Wrights. The second flight, on 18 March, also ending in a crash, covered only 40 yards and proved the need for lateral control.

Span 43 ft 4 in (13.2 m); wing area 385 sq ft (35.76 sq m); gross weight 570 lb (258 kg); powerplant Curtiss 40 hp air-cooled V-8.

Aerodrome No.2, White Wing The second AEA aeroplane was White Wing, sponsored by Baldwin. It was very similar to Red Wing, except for the substitution of three wheels for the ice runners, and used the same engine. The most important innovation was the addition of movable lateral control surfaces on all four wingtips that later came to be called ailerons. In principle, these had the same effect as the Wright's wing-warping, but Curtiss claimed mechanical and control differences. The method of control reflected Curtiss's motorcyle experience - a yoke embraced the pilot's shoulders - when he wanted to bank for a turn, he leaned in the desired direction and the proper control movement was automatically applied.

White Wing made four flights, the first on 18 May, 1908, again with Baldwin at the controls. Distance was 93 yards (85 m) at a height of 10 ft (3 m). Longest flight was the third, at 339 yards (310m) with Curtiss flying. While Wing crashed on 23 May after McCurdy had flown 183 yards (167 m).

Span 42 ft 3 in (12.87 m); wing area 408 sq ft (37.9 sq m); gross weight 605 lb (274 kg).

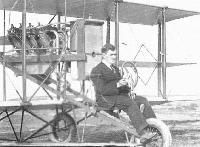

Aerodrome No.4, Silver Dart The Silver Dart was less famous than June Bug but was a far more successful flying machine. Sponsored by McCurdy, it had a 50 hp Curtiss water-cooled V-8 engine, biplane forward elevators, and no rear stabilizer. Instead of being connected directly, the engine drove the propeller by a chain and sprockets.

First flight was at Hammondsport on 6 December, 1908, with McCurdy flying. It was moved to Baddeck where it made the first flight in Canada on 23 February, 1909, again with McCurdy piloting.

Span 49 ft (14,93 m); wing area 420 sq ft (39 sq m); gross weight 860 lb (390 kg).

First flight was at Hammondsport on 6 December, 1908, with McCurdy flying. It was moved to Baddeck where it made the first flight in Canada on 23 February, 1909, again with McCurdy piloting.

Span 49 ft (14,93 m); wing area 420 sq ft (39 sq m); gross weight 860 lb (390 kg).

AEA Aerodrome No.4, the canard Silver Dart. was built at Hammondsport but did most of its flying in Nova Scotia, where it became the first aeroplane to fly in Canada.

A grim-visaged Glenn Curtiss sits in the Silver Dart. Note the belt-driven propeller and individual carburellors ror each cylinder of the 50 hp V-8 engine.

Beachey Tractor. Although he had left the Curtiss Exhibition Company in 1911 to do his own air show work, Lincoln Beachey retained a preference for Curtiss aeroplanes. Believing that the tractor type would be advantageous in his work, Beaehey collaborated with Curtiss early in 1913 on the design of a single-seat open-fuselage tractor biplane powered with a 90 hp Curtiss OX engine.

The tractor did not perform as expected, and Beachey had a scaled-down Curtiss pusher type built by Warren Eaton and later a tractor monoplane by Glenn L. Martin. He was killed when the Martin broke up in the air at San Francisco on 14 March, 1915.

The tractor did not perform as expected, and Beachey had a scaled-down Curtiss pusher type built by Warren Eaton and later a tractor monoplane by Glenn L. Martin. He was killed when the Martin broke up in the air at San Francisco on 14 March, 1915.

The second Curtiss tractor landplane design was an aerobatic machine designed to the requirements ofexhibition pilot Lincoln Beachey. It was not a success and Beachey went elsewhere for a tractor.

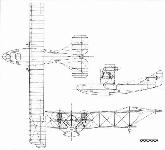

Evolution of the Curtiss Pusher

In the period 1909-12, the major Curtiss design and manufacturing effort was directed to the development of a basic model that historians later called 'The Curtiss Pusher'. This was a direct descendent of the final AEA design, the Silver Dart. The major change was redesign of the wings to simple rectangular shape with no dihedral and relocation of the ailerons to the mid-points of the forward wing struts. The aileron relocation was done partly for efficiency but mainly to separate those surfaces from the wing in an attempt to avoid infringement of the Wright patent.

The earliest models were all single seaters, with the pilot seated slightly ahead of the wing. The single water-cooled Curtiss engine of 26 to 90 hp was mounted between the wings behind him, driving a single propeller. Forward elevator controls were carried on bamboo booms ahead of the pilot while a fixed stabilizer and movable rudder were carried on booms behind. The ailerons were operated by shoulder yoke, the pilot leaning in the direction he wished to bank, a 'natural' function for Curtiss, the former motorcycle champion. As on the AEA types, the wings were originally covered on the top surfaces only.

Logical improvements such as more powerful engines and double-surfaced wings improved performance and made a practical vehicle of the pusher by allowing two people to be carried. Curtiss then developed a throw-over control column whereby the single control wheel could be moved from one pilot to the other. This was an improvement on the Contemporary Wright brothers' system, where two pilots shared one-and-a-half sets of controls, and developed into recognized 'left-seat' and 'right-seat' Wright pilots.

No designations were assigned to the early Curtiss models, which were merely identified according to their purchaser or the specific purpose for which they were built. As custom-built machines, each incorporated differences from its predecessor, and then took on additions that have further complicated the historians' recognition problems. Improved models illustrated in contemporary publications were identified only as 'The New Curtiss' or 'The XX Horsepower Curtiss',

Even after the assignment of official model designations, positive identification of individual Curtiss pushers of the 1910-13 era was impossible, A number of close copies were built by outsiders, who either used Curtiss-built machines as a guide or built from the workable plans that appeared in contemporary books and magazines and made various changes, Also, special features of aeroplanes custom-built by Curtiss, plus modifications and the use of parts from other models, further complicate the identity problem.

From 1909 into 1911, however, the major evolutionary changes in the pusher resulted in the recognition of the four distinct 'Types' listed here:

Type I - Single-seat machine with single-surface wings, biplane forward elevator on long forward booms, and fixed horizontal stabilizer located with rear rudder on long rear booms.

Type II -Single-seater similar to Type I except double-surfaced wings, ailerons relocated to rear struts.

Type III - Single- or two-seater with monoplane forward elevator on shortened booms, elevators added to horizontal stabilizer.

Type IV - Military model of Type III with wings built in short interchangeable sections to facilitate breakdown to small units for transport on Army wagons.

The Curtiss pushers started with a basic design and improved upon it, so the four definitive types seen from 1909 into 1911 can be regarded as developmental or evolutionary rather than experimental.

An oddity in the evolution of the pusher is inconsistency of later application of the forward elevator, which started as a biplane surface and then was simplified to a monoplane type before disappearing altogether. The one contribution that Augustus Herring is credited with making to Curtiss aeroplanes is the small forward vertical fin used on some of the 1909-11 models.

The need for the forward elevator was originally questioned by stunt pilot Lincoln Beachey, who successfully eliminated it from his exhibition machine late in 1910. While several experimental models subsequently flew without forward elevators, production aeroplanes continued to be delivered with them into 1912. On some Model Es, where the short forward booms formed an essential part of the bracing, the booms were retained after the elevators were removed subsequent to delivery. Four significant developmental pushers are now described:

Curtiss No.1, Gold Bug or Golden Flyer The first Curtiss-built aeroplane designated as such was the single-seat model ordered by the Aeronautical Society of New York on 2 March, 1909, The purchase price of $5,000 included instruction for two Society members, With no designation, No, 1 was initially called Gold Bug because of the golden tint of the varnished fabric but later officially became the Golden Flyer, Although built after the Herring-Curtiss affiliation, Curtiss specifically excluded No.1 from the inventory of the new company.

Curtiss-Herring No.1, Reims Racer At the urging of the Aeronautical Society ofNew York to represent it in the 1909 Gordon Bennett Cup Race in France, Curtiss built a larger version of No. 1 and installed a new 60 hp V-8 engine, which was a carefully-guarded secret until the racer was set up in France in August.

Flying against the clock rather than other aeroplanes, Curtiss completed the 20 km closed course at a world's record 43,35 mph (69,76 km/h). The Reims Racer was later used by Curtiss and his pilots for exhibition work and other record flights in the United States.

Hudson Flyer In 1909, Glenn Curtiss decided to try for the $10,000 prize posted by the New York World newspaper for the first flight between Albany, the capital city or New York State, and New York City. After many delays due to weather, the record 156-mile (251 km) flight was made on 29 May, 1910. The start was at Albany, with a refuelling stop at Poughkeepsie and a precautionary stop within the northern city limits of New York before the final landing on Governor's Island.

The Hudson Flyer was a stock model Curtiss or the period, modified for the flight. Since the entire route was over the Hudson, emergency flotation gear was added. To preclude nosing over on alighting on water, a hydrovane was installed ahead of the nosewheel at the suggestion of Charles Willard, who had made two unintentional alightings in the Golden Flyer. To carry the weight or the extra equipment and fuel, the area of the upper wing was increased by adding strut-braced extensions to the tips.

Beachey Special Curtiss exhibition pilot Lincoln Beachey, whose early fame came from dirigible racing, was the leading American stunt pilot of the 1911-14 period and was the first American pilot to perform a loop. He could have been the first in the world, but when he proposed the idea to Curtiss in 1912, Curtiss said it couldn't be done and forbade him to try.

In 1911, to improve Beachey's performance, Curtiss built him a special extra-strength and higher powered showplane. As requested, this did not have forward elevators since Beachey had already proved that the standard model could do without them. Beachey used his Special to set the world's altitude record or 11,642 ft (3,548 m) on 20 August, 1911.

By mid-1911, when Curtiss pushers were pretty well standardized and being manufactured in what could be considered production quantities, Curtiss began to use specific designations in its advertizing. The following descriptions of officially-designated D and E models are reproduced verbatim from the 1911 Curtiss Aeroplane Company catalogue. The Curtiss A to C designations, if used at all, cannot be correlated to specific aeroplanes or configurations; the designation Model C is seen on some photographs or June Bug, apparently added by later misguided historians.

Model D

SPECIFICATIONS

Width - Planes, over all, 33 feet, 4 inches.

Length - Front to rear control, 25 feet, 9 inches.

Height - From ground to highest points, 7 feet 5 1/2 inches.

DESCRIPTION AND PRICES

Model D-4 - Equipped with a 4-cylinder, 40 H. P., water-cooled Curtiss motor. An excellent machine for exhibition work, endurance, etc. Speed, 45 miles per hour. Weight ready for flight, 550 pounds. Weight, packed for shipment, 950 pounds. Price, complete for shipment. $4,500

Model D-8 - Equipped with an 8-cylinder, 60 H. P., water-cooled Curtiss motor. Entire outfit identical with that used by the famous aviators of The Curtiss Exhibition Co. The safest machine, and the most suitable for a confined space. Speed 60 miles per hour. Weight, ready for flight, 650 pounds. Weight, packed for shipment, 1,000 pounds. Price, complete for shipment $5,000

Model D-8-75 - Same as Model D, but equipped with an 8-cylinder, 75 H. P., water-cooled Curtiss motor. Capable of developing a speed of 70 miles an hour. For speed and cross-country races. Weight, ready for flight, 700 pounds. Weight, packed for shipment, 1,050 pounds. Price, complete for shipment $3,500

Model E

SPECIFICATIONS

Width - Planes, over all, 35 feet, 4 inches.

Length - Front to rear control, 25 feet, 9 inches.

Height - From ground to highest point, 8 feet.

DESCRIPTION AND PRICES

Model E-4 - Equipped with a 4-cylinder, 40 h.p. water-cooled Curtiss motor. This machine is a slow, strong flying aeroplane, especially suitable for aviation schools and beginners. It is also available for high, dry altitudes. Speed, 40 miles per hour. Weight, ready for flight, 600 pounds. Weight, packed for shipment, 1000 pounds. Price, complete for shipment $4,500

Model E-8 - Equipped with an 8-cylinder, 60 h. p. water-cooled Curtiss motor. A machine that combines speed with the advantages of weight-carrying. Equipped with the Curtiss alternating dual control system. A machine that makes aviation a sport. Speed, 55 miles per hour. Weight, ready for flight, 700 pounds. Weight, packed for shipment, 1050 pounds. Price, complete for shipment $5,000

Model E-8-75 - The same as model E-8, but equipped with an 8-cylinder, 75 h. p. Curtiss motor. The surplus power gives greater speed as well as more weight-carrying possibilities. Speed, 60 miles per hour. Weight, ready for flight, 750 pounds. Weight, packed for shipment, 1,100 pounds. Price, complete for shipment $5,500

DESCRIPTION AND PRICES

Model D-8 - Exhibition type with hydro equipment, in addition to the regular chassis. Price, complete. $5,500

Model E-8-75 - The "triad" passenger carrying hydroaeroplane, which is identical with Model E when the hydro is not attached. This machine is equipped with a 75 h. p. motor. Price $6,000

With standardized Curtiss pushers in production and being advertized world-wide, business was brisk by 1912. The aeroplane and engine factories were enlarged and licences were issued for the manufacture of pushers in other countries.

While a basic design was sold, there were special custom variations. Aviatrix Ruth Law, for example, had learned to fly on a Wright aeroplane with its peculiar control system and could not make the transition to the Curtiss system. Consequently, her custom-built Curtiss D was fitted with Wright controls.

Between them, the US Army and Navy bought twelve Curtiss land plane pushers in 1911 and 1912, and these are now discussed.

The US Army's second aeroplane was an existing model ordered on 13 March, 1911, for $6,000 and was delivered the same month. Identified as Signal Corps Aeroplane No.2, this was a single-seat Model D powered with a 60 hp Curtiss engine. The engine was soon replaced with a 40 hp model and the front elevator was removed some time later. No.2 ended its days as a 'Penguin' ground trainer after the Army grounded all of its pusher trainers in February 1914. Rebuilt to original configuration, it is now in The National Air Museum of the Smithsonian Institution.

Three two-seat Curtiss Es also went to the Army - S.C. numbers 6, 8, and 23. The original 40 hp engine of No.6 was exchanged for the 60 hp model of the smaller S.C. No.2, S.C.8 was eventually converted to a seaplane, and S.C.23 was sold out of the Service after the pushers were grounded.

The poor safety records of both the Wright and Curtiss pusher trainers at the Army's North Island school brought about a demand for safer tractor-type equipment and led directly to the development of the Curtiss J and N models that culminated in the immortal IN series.

Of eight Curtiss pushers bought by the US Navy between 1911 and 1913, only one was delivered as a landplane, and it was soon converted to a seaplane.

Shortly after World War I, a special 1912-style Curtiss pusher was built under Glenn Curtiss's personal direction at Garden City, evidently for nostalgic reasons. Such minor refinements as improved fittings and a revised control system featuring a rudder bar and wheel control for the ailerons were incorporated. Long a fixture at Curtiss Field, this machine was in the Roosevelt Field Museum until World War II and is now at The National Air Museum.

In the period 1909-12, the major Curtiss design and manufacturing effort was directed to the development of a basic model that historians later called 'The Curtiss Pusher'. This was a direct descendent of the final AEA design, the Silver Dart. The major change was redesign of the wings to simple rectangular shape with no dihedral and relocation of the ailerons to the mid-points of the forward wing struts. The aileron relocation was done partly for efficiency but mainly to separate those surfaces from the wing in an attempt to avoid infringement of the Wright patent.

The earliest models were all single seaters, with the pilot seated slightly ahead of the wing. The single water-cooled Curtiss engine of 26 to 90 hp was mounted between the wings behind him, driving a single propeller. Forward elevator controls were carried on bamboo booms ahead of the pilot while a fixed stabilizer and movable rudder were carried on booms behind. The ailerons were operated by shoulder yoke, the pilot leaning in the direction he wished to bank, a 'natural' function for Curtiss, the former motorcycle champion. As on the AEA types, the wings were originally covered on the top surfaces only.

Logical improvements such as more powerful engines and double-surfaced wings improved performance and made a practical vehicle of the pusher by allowing two people to be carried. Curtiss then developed a throw-over control column whereby the single control wheel could be moved from one pilot to the other. This was an improvement on the Contemporary Wright brothers' system, where two pilots shared one-and-a-half sets of controls, and developed into recognized 'left-seat' and 'right-seat' Wright pilots.

No designations were assigned to the early Curtiss models, which were merely identified according to their purchaser or the specific purpose for which they were built. As custom-built machines, each incorporated differences from its predecessor, and then took on additions that have further complicated the historians' recognition problems. Improved models illustrated in contemporary publications were identified only as 'The New Curtiss' or 'The XX Horsepower Curtiss',

Even after the assignment of official model designations, positive identification of individual Curtiss pushers of the 1910-13 era was impossible, A number of close copies were built by outsiders, who either used Curtiss-built machines as a guide or built from the workable plans that appeared in contemporary books and magazines and made various changes, Also, special features of aeroplanes custom-built by Curtiss, plus modifications and the use of parts from other models, further complicate the identity problem.

From 1909 into 1911, however, the major evolutionary changes in the pusher resulted in the recognition of the four distinct 'Types' listed here:

Type I - Single-seat machine with single-surface wings, biplane forward elevator on long forward booms, and fixed horizontal stabilizer located with rear rudder on long rear booms.

Type II -Single-seater similar to Type I except double-surfaced wings, ailerons relocated to rear struts.

Type III - Single- or two-seater with monoplane forward elevator on shortened booms, elevators added to horizontal stabilizer.

Type IV - Military model of Type III with wings built in short interchangeable sections to facilitate breakdown to small units for transport on Army wagons.

The Curtiss pushers started with a basic design and improved upon it, so the four definitive types seen from 1909 into 1911 can be regarded as developmental or evolutionary rather than experimental.

An oddity in the evolution of the pusher is inconsistency of later application of the forward elevator, which started as a biplane surface and then was simplified to a monoplane type before disappearing altogether. The one contribution that Augustus Herring is credited with making to Curtiss aeroplanes is the small forward vertical fin used on some of the 1909-11 models.

The need for the forward elevator was originally questioned by stunt pilot Lincoln Beachey, who successfully eliminated it from his exhibition machine late in 1910. While several experimental models subsequently flew without forward elevators, production aeroplanes continued to be delivered with them into 1912. On some Model Es, where the short forward booms formed an essential part of the bracing, the booms were retained after the elevators were removed subsequent to delivery. Four significant developmental pushers are now described:

Curtiss No.1, Gold Bug or Golden Flyer The first Curtiss-built aeroplane designated as such was the single-seat model ordered by the Aeronautical Society of New York on 2 March, 1909, The purchase price of $5,000 included instruction for two Society members, With no designation, No, 1 was initially called Gold Bug because of the golden tint of the varnished fabric but later officially became the Golden Flyer, Although built after the Herring-Curtiss affiliation, Curtiss specifically excluded No.1 from the inventory of the new company.

Curtiss-Herring No.1, Reims Racer At the urging of the Aeronautical Society ofNew York to represent it in the 1909 Gordon Bennett Cup Race in France, Curtiss built a larger version of No. 1 and installed a new 60 hp V-8 engine, which was a carefully-guarded secret until the racer was set up in France in August.

Flying against the clock rather than other aeroplanes, Curtiss completed the 20 km closed course at a world's record 43,35 mph (69,76 km/h). The Reims Racer was later used by Curtiss and his pilots for exhibition work and other record flights in the United States.

Hudson Flyer In 1909, Glenn Curtiss decided to try for the $10,000 prize posted by the New York World newspaper for the first flight between Albany, the capital city or New York State, and New York City. After many delays due to weather, the record 156-mile (251 km) flight was made on 29 May, 1910. The start was at Albany, with a refuelling stop at Poughkeepsie and a precautionary stop within the northern city limits of New York before the final landing on Governor's Island.

The Hudson Flyer was a stock model Curtiss or the period, modified for the flight. Since the entire route was over the Hudson, emergency flotation gear was added. To preclude nosing over on alighting on water, a hydrovane was installed ahead of the nosewheel at the suggestion of Charles Willard, who had made two unintentional alightings in the Golden Flyer. To carry the weight or the extra equipment and fuel, the area of the upper wing was increased by adding strut-braced extensions to the tips.

Beachey Special Curtiss exhibition pilot Lincoln Beachey, whose early fame came from dirigible racing, was the leading American stunt pilot of the 1911-14 period and was the first American pilot to perform a loop. He could have been the first in the world, but when he proposed the idea to Curtiss in 1912, Curtiss said it couldn't be done and forbade him to try.

In 1911, to improve Beachey's performance, Curtiss built him a special extra-strength and higher powered showplane. As requested, this did not have forward elevators since Beachey had already proved that the standard model could do without them. Beachey used his Special to set the world's altitude record or 11,642 ft (3,548 m) on 20 August, 1911.

By mid-1911, when Curtiss pushers were pretty well standardized and being manufactured in what could be considered production quantities, Curtiss began to use specific designations in its advertizing. The following descriptions of officially-designated D and E models are reproduced verbatim from the 1911 Curtiss Aeroplane Company catalogue. The Curtiss A to C designations, if used at all, cannot be correlated to specific aeroplanes or configurations; the designation Model C is seen on some photographs or June Bug, apparently added by later misguided historians.

Model D

SPECIFICATIONS

Width - Planes, over all, 33 feet, 4 inches.

Length - Front to rear control, 25 feet, 9 inches.

Height - From ground to highest points, 7 feet 5 1/2 inches.

DESCRIPTION AND PRICES

Model D-4 - Equipped with a 4-cylinder, 40 H. P., water-cooled Curtiss motor. An excellent machine for exhibition work, endurance, etc. Speed, 45 miles per hour. Weight ready for flight, 550 pounds. Weight, packed for shipment, 950 pounds. Price, complete for shipment. $4,500

Model D-8 - Equipped with an 8-cylinder, 60 H. P., water-cooled Curtiss motor. Entire outfit identical with that used by the famous aviators of The Curtiss Exhibition Co. The safest machine, and the most suitable for a confined space. Speed 60 miles per hour. Weight, ready for flight, 650 pounds. Weight, packed for shipment, 1,000 pounds. Price, complete for shipment $5,000

Model D-8-75 - Same as Model D, but equipped with an 8-cylinder, 75 H. P., water-cooled Curtiss motor. Capable of developing a speed of 70 miles an hour. For speed and cross-country races. Weight, ready for flight, 700 pounds. Weight, packed for shipment, 1,050 pounds. Price, complete for shipment $3,500

Model E

SPECIFICATIONS

Width - Planes, over all, 35 feet, 4 inches.

Length - Front to rear control, 25 feet, 9 inches.

Height - From ground to highest point, 8 feet.

DESCRIPTION AND PRICES

Model E-4 - Equipped with a 4-cylinder, 40 h.p. water-cooled Curtiss motor. This machine is a slow, strong flying aeroplane, especially suitable for aviation schools and beginners. It is also available for high, dry altitudes. Speed, 40 miles per hour. Weight, ready for flight, 600 pounds. Weight, packed for shipment, 1000 pounds. Price, complete for shipment $4,500

Model E-8 - Equipped with an 8-cylinder, 60 h. p. water-cooled Curtiss motor. A machine that combines speed with the advantages of weight-carrying. Equipped with the Curtiss alternating dual control system. A machine that makes aviation a sport. Speed, 55 miles per hour. Weight, ready for flight, 700 pounds. Weight, packed for shipment, 1050 pounds. Price, complete for shipment $5,000

Model E-8-75 - The same as model E-8, but equipped with an 8-cylinder, 75 h. p. Curtiss motor. The surplus power gives greater speed as well as more weight-carrying possibilities. Speed, 60 miles per hour. Weight, ready for flight, 750 pounds. Weight, packed for shipment, 1,100 pounds. Price, complete for shipment $5,500

DESCRIPTION AND PRICES

Model D-8 - Exhibition type with hydro equipment, in addition to the regular chassis. Price, complete. $5,500

Model E-8-75 - The "triad" passenger carrying hydroaeroplane, which is identical with Model E when the hydro is not attached. This machine is equipped with a 75 h. p. motor. Price $6,000

With standardized Curtiss pushers in production and being advertized world-wide, business was brisk by 1912. The aeroplane and engine factories were enlarged and licences were issued for the manufacture of pushers in other countries.

While a basic design was sold, there were special custom variations. Aviatrix Ruth Law, for example, had learned to fly on a Wright aeroplane with its peculiar control system and could not make the transition to the Curtiss system. Consequently, her custom-built Curtiss D was fitted with Wright controls.

Between them, the US Army and Navy bought twelve Curtiss land plane pushers in 1911 and 1912, and these are now discussed.

The US Army's second aeroplane was an existing model ordered on 13 March, 1911, for $6,000 and was delivered the same month. Identified as Signal Corps Aeroplane No.2, this was a single-seat Model D powered with a 60 hp Curtiss engine. The engine was soon replaced with a 40 hp model and the front elevator was removed some time later. No.2 ended its days as a 'Penguin' ground trainer after the Army grounded all of its pusher trainers in February 1914. Rebuilt to original configuration, it is now in The National Air Museum of the Smithsonian Institution.

Three two-seat Curtiss Es also went to the Army - S.C. numbers 6, 8, and 23. The original 40 hp engine of No.6 was exchanged for the 60 hp model of the smaller S.C. No.2, S.C.8 was eventually converted to a seaplane, and S.C.23 was sold out of the Service after the pushers were grounded.

The poor safety records of both the Wright and Curtiss pusher trainers at the Army's North Island school brought about a demand for safer tractor-type equipment and led directly to the development of the Curtiss J and N models that culminated in the immortal IN series.

Of eight Curtiss pushers bought by the US Navy between 1911 and 1913, only one was delivered as a landplane, and it was soon converted to a seaplane.

Shortly after World War I, a special 1912-style Curtiss pusher was built under Glenn Curtiss's personal direction at Garden City, evidently for nostalgic reasons. Such minor refinements as improved fittings and a revised control system featuring a rudder bar and wheel control for the ailerons were incorporated. Long a fixture at Curtiss Field, this machine was in the Roosevelt Field Museum until World War II and is now at The National Air Museum.

Glenn Curtiss and Curtiss-Herring No.1, the aeroplane with which he won the 1909 Gordon Bennett Cup at Reims, France.

The Hudson Flyer in which Glenn Curtiss won $10,000 for a flight from Albany to New York City in May 1909. The extended upper wing supported the weight of the emergency flotation gear used for the 156-mile overwater flight

The Model E was a two-seater, but with only 40 hp, the US Army's Aeroplane No.6 of 1911 was rigged as a single-seater.

A true replica of a 1912 Curtiss pusher built by Glenn Curtiss and associates at Garden City after World War I. Powerplant was a war-surplus Curtiss OX-5.

An early Curtiss promotional effort resulted in pilot Eugene Ely making the first take off of an aeroplane from a ship, on 10 November, 1910. This is the second take off, made after landing on the uss Pennsylvania, on 18 January, 1911.

Famous acrobatic pilot Lincoln Beachey seated in his special Curtiss pusher fitted with standard controls, including shoulder-yoke for the ailerons.

aviatrix Ruth Law learned to fly on a Wright aeroplane and had to have this entirely difierent control system installed in her Curtiss.

Ely Monoplane. In 1910, Curtiss exhibition pilot Eugene Ely ordered a monoplane to be built by Curtiss. While this was essentially a single-wing version of the current Curtiss biplane, it was Ely's concept and should not be considered a Curtiss design.

The Ely monoplane was built to the special order of Curtiss exhibition pilot Eugene Ely and was not a true Curtiss design.

Seaplane Development

The first American attempt to fly from the water was made by the AEA in 1908 with the Loon, but it was unable to take off. In June 1910, Curtiss successfully alighted on Lake Keuka in a Type III pusher with a canoe secured beneath it; however, the aeroplane would not take off for the same reason as the Loon - the high hydrodynamic drag of the rounded canoe hull prevented the machine from reaching flying speed.

Curtiss soon realized that a flat-bottomed float could plane over the water, offering less drag and consequently more speed for a given power. A long series of experimental pontoons, or floats, was then developed and tried on standard Curtiss pushers at San Diego during winter 1910-11.

Although the Frenchman Henri Fabre had successfully taken off from water in a powered aeroplane on 28 March, 1910, Curtiss is recognized as the inventor of the practical seaplane. The original short Curtiss floats had flat bottoms for their entire length; later, long designs featured the hydroplane step, located slightly behind the aeroplane's centre of gravity, that Curtiss had developed for his flying-boat in 1912, combined with V-bottoms.

The single main float with wingtip floats standardized by Curtiss early in 1911 remained in use on most US Navy seaplanes to the end of their service in 1960; the twin-float arrangement of the 1908 Loon is in universal use on civil seaplanes today.

Experimental Hydros, 1911

The first successful flight of what was originally called a hydroaeroplane or simply hydro, but is now known as a seaplane, was made on 26 January, 1911. It used a clumsy tandem-float arrangement featuring a main float six ft (1.82 m) wide by five ft (1.52 m) long under the centre section, a smaller float forward, and a hydrofoil ahead of that to keep the bow from submerging at high speed. The wide design of the main float served two purposes. By being wide it was expected to function as an auxiliary wing to generate useful lift; also, its width would keep the spray pattern well outboard of the pusher propeller. Being short, it did not provide longitudinal stability on the water thus necessitating the forward float.

By 1 February, a new arrangement was introduced, comprising a sled-shaped single float 12 ft (3,65 m) long, two ft (60 cm) wide and a foot (30 cm) deep, under the pilot and engine to provide longitudinal stability; small floats for lateral stability were under the wingtips.

At first, the main float was not compartmented. On a flight at Hammondsport, Curtiss took off in a hydro but a considerable amount of water had got into the float and as he nosed down to alight, all the water ran to the bow of the float and made the machine so nose heavy that Curtiss was unable to raise the nose and crashed into the lake. He recognized the problem as soon as it appeared and fortunately survived to correct it.

An early refinement of the hydro was to eliminate the booms that supported the forward elevator and place a monoplane elevator on the bow of the float. As on contemporary landplanes, the hydro's forward elevators were soon eliminated.

Tractor Hydro. The second Curtiss hydro was a notable exception to the standard pusher design. The un-named machine that Curtiss used for his flight from North Island to the cruiser Pennsylvania was an otherwise standard Type III pusher airframe with the engine installed ahead of the wing as a tractor to keep the propeller out of the spray. The pilot was seated behind the wings and the forward elevator was eliminated. Curtiss didn't like the arrangement mainly because of the discomfort of sitting in the propeller blast and engine exhaust; the problem of spray on the propeller on subsequent pusher seaplanes was reduced somewhat by the addition of horizontal spray deflectors to the top of the main float ahead of the propeller.

Triad. With the conventional landplane converted to water operations by the substitution of pontoons for wheels, it was only natural to develop an aeroplane to operate from both elements. Curtiss achieved this by adding retractable wheels under the lower wings of a hydro and adding a nosewheel to the bow of the float. The resulting amphibian, named Triad by Curtiss, was successfully demonstrated at North Island on 25 February, 1911.

Although still in use today, the popularity of amphibious floatplanes has always been limited by the double weight handicap of the floats and the necessary wheel-retracting mechanism. The most popular amphibians have all been flying-boat types.

US Navy A-1. The Navy's first aeroplane, a 50 hp Curtiss Model E seaplane costing $5,500, was tested by Glenn Curtiss on 30 June, 1911, and turned over to Navy pilot T. G. Ellyson at Hammondsport the same day. On 7 July, the75 hp V-8 engine originally intended for the A-1 was installed. The A-1, later AH-1 under the 1914 Naval designation system, operated as a straight seaplane, as a Triad amphibian, and as a landplane.

Among the experiments undertaken with A-1 were take off down an inclined wire, with a groove in the bottom of the float to maintain alignment, and the Navy's first attempt to launch an aeroplane from a compressed-air catapult. After sixty flights totalling 285 hours, plus numerous rebuilds, A-1 is believed to have been struck off charge on 16 October, 1914.

By the autumn of 1911 Curtiss was advertizing hydros on the open market. The standardized float gear was available for an additional $500 when buying a standard Model D or E land plane. The hydros were nearly as popular as the landplanes and were licensed to overseas manufacturers in 1912.

The US Navy bought fourteen pushers with detail variations between 1911 and 1914. The combined Navy Type I serial numbers were A-1, A-2 (delivered as a landplane but converted to hydro), A-3, A-4, AH-8, AH-9, and AH-11/18. AH-8 was turned over to the Army, was still in Army hands in 1919, and was then stored. It was refurbished for a brief flight on 10 February, 1928. AH-9 was rebuilt and redesignated as an AH-8 type, Navy serial No. A-83.

The first American attempt to fly from the water was made by the AEA in 1908 with the Loon, but it was unable to take off. In June 1910, Curtiss successfully alighted on Lake Keuka in a Type III pusher with a canoe secured beneath it; however, the aeroplane would not take off for the same reason as the Loon - the high hydrodynamic drag of the rounded canoe hull prevented the machine from reaching flying speed.

Curtiss soon realized that a flat-bottomed float could plane over the water, offering less drag and consequently more speed for a given power. A long series of experimental pontoons, or floats, was then developed and tried on standard Curtiss pushers at San Diego during winter 1910-11.

Although the Frenchman Henri Fabre had successfully taken off from water in a powered aeroplane on 28 March, 1910, Curtiss is recognized as the inventor of the practical seaplane. The original short Curtiss floats had flat bottoms for their entire length; later, long designs featured the hydroplane step, located slightly behind the aeroplane's centre of gravity, that Curtiss had developed for his flying-boat in 1912, combined with V-bottoms.

The single main float with wingtip floats standardized by Curtiss early in 1911 remained in use on most US Navy seaplanes to the end of their service in 1960; the twin-float arrangement of the 1908 Loon is in universal use on civil seaplanes today.

Experimental Hydros, 1911

The first successful flight of what was originally called a hydroaeroplane or simply hydro, but is now known as a seaplane, was made on 26 January, 1911. It used a clumsy tandem-float arrangement featuring a main float six ft (1.82 m) wide by five ft (1.52 m) long under the centre section, a smaller float forward, and a hydrofoil ahead of that to keep the bow from submerging at high speed. The wide design of the main float served two purposes. By being wide it was expected to function as an auxiliary wing to generate useful lift; also, its width would keep the spray pattern well outboard of the pusher propeller. Being short, it did not provide longitudinal stability on the water thus necessitating the forward float.

By 1 February, a new arrangement was introduced, comprising a sled-shaped single float 12 ft (3,65 m) long, two ft (60 cm) wide and a foot (30 cm) deep, under the pilot and engine to provide longitudinal stability; small floats for lateral stability were under the wingtips.

At first, the main float was not compartmented. On a flight at Hammondsport, Curtiss took off in a hydro but a considerable amount of water had got into the float and as he nosed down to alight, all the water ran to the bow of the float and made the machine so nose heavy that Curtiss was unable to raise the nose and crashed into the lake. He recognized the problem as soon as it appeared and fortunately survived to correct it.

An early refinement of the hydro was to eliminate the booms that supported the forward elevator and place a monoplane elevator on the bow of the float. As on contemporary landplanes, the hydro's forward elevators were soon eliminated.

Tractor Hydro. The second Curtiss hydro was a notable exception to the standard pusher design. The un-named machine that Curtiss used for his flight from North Island to the cruiser Pennsylvania was an otherwise standard Type III pusher airframe with the engine installed ahead of the wing as a tractor to keep the propeller out of the spray. The pilot was seated behind the wings and the forward elevator was eliminated. Curtiss didn't like the arrangement mainly because of the discomfort of sitting in the propeller blast and engine exhaust; the problem of spray on the propeller on subsequent pusher seaplanes was reduced somewhat by the addition of horizontal spray deflectors to the top of the main float ahead of the propeller.

Triad. With the conventional landplane converted to water operations by the substitution of pontoons for wheels, it was only natural to develop an aeroplane to operate from both elements. Curtiss achieved this by adding retractable wheels under the lower wings of a hydro and adding a nosewheel to the bow of the float. The resulting amphibian, named Triad by Curtiss, was successfully demonstrated at North Island on 25 February, 1911.

Although still in use today, the popularity of amphibious floatplanes has always been limited by the double weight handicap of the floats and the necessary wheel-retracting mechanism. The most popular amphibians have all been flying-boat types.

US Navy A-1. The Navy's first aeroplane, a 50 hp Curtiss Model E seaplane costing $5,500, was tested by Glenn Curtiss on 30 June, 1911, and turned over to Navy pilot T. G. Ellyson at Hammondsport the same day. On 7 July, the75 hp V-8 engine originally intended for the A-1 was installed. The A-1, later AH-1 under the 1914 Naval designation system, operated as a straight seaplane, as a Triad amphibian, and as a landplane.

Among the experiments undertaken with A-1 were take off down an inclined wire, with a groove in the bottom of the float to maintain alignment, and the Navy's first attempt to launch an aeroplane from a compressed-air catapult. After sixty flights totalling 285 hours, plus numerous rebuilds, A-1 is believed to have been struck off charge on 16 October, 1914.

By the autumn of 1911 Curtiss was advertizing hydros on the open market. The standardized float gear was available for an additional $500 when buying a standard Model D or E land plane. The hydros were nearly as popular as the landplanes and were licensed to overseas manufacturers in 1912.

The US Navy bought fourteen pushers with detail variations between 1911 and 1914. The combined Navy Type I serial numbers were A-1, A-2 (delivered as a landplane but converted to hydro), A-3, A-4, AH-8, AH-9, and AH-11/18. AH-8 was turned over to the Army, was still in Army hands in 1919, and was then stored. It was refurbished for a brief flight on 10 February, 1928. AH-9 was rebuilt and redesignated as an AH-8 type, Navy serial No. A-83.

The second Curtiss seaplane had the engine forward and the pilot aft. Glenn Curtiss used this machine to fly from North Island to the cruiser Pennsylvania anchored in San Diego Bay.

Glenn Curtiss demonstrates the Triad, the first successful amphibian, at San Diego in February 1911.

The standard Curtiss hydro of late 1911 still had the forward elevator. but the forward booms were no longer used and the elevator was mounted on the float.

Flying-boat Development

Following the perfection of the hydro aeroplane or seaplane, which was simply a landplane with floats substituted for wheels, Curtiss sought to develop a true flying-boat. The distinction lay in the fact that the boat-like hull formed an integral part of the structure rather than being an interchangeable accessory as on the hydro. Although others were working on the same idea concurrently, Glenn Curtiss is recognized as the inventor of the aeroplane configuration known as the flying-boat. The basic layout that he developed in 1912 became the world standard for single-engined flying-boats and is still being used.

Flying-boat No.1. The first Curtiss flying-boat, tried at San Diego on 10 January, 1912, was more a hydro than a true boat. A wide hull, only slightly longer than the standard Curtiss pontoon, was attached under the lower wing of the de-engined airframe of the tractor seaplane. A single 60 hp engine was mounted in the hull and drove two tractor propellers through chains in Curtiss's only deliberate adaptation of a Wright brothers' feature. There were two side-by-side seats in a cockpit behind the wing.

Although No.1 was unable to take off, the experiment did indicate that the flying-boat concept was practicable. Subsequent developments were made at Hammondsport.

Flying-boat No.2, The Flying Fish. The first successful flying-boat, built at Hammondsport, featured a full-length flat-bottomed hull that supported both the wings and tail. To keep the horizontal tail surfaces out of the water, they were sited part-way up the long vertical fin.

The engine was a 75 hp Curtiss Model O installed between the wings as on standard pushers. An indication of the fact that Flying-boat No.2 was built quickly and cheaply to prove a concept rather than to achieve optimum performance is shown by the initial use of an old set of 1910-style single surface wings. Forward elevators were also fixed to the bow at a time when they were being omitted from production aeroplanes. Flying-boat No.2 underwent considerable modification and refinement within a short period, ending up with double surface E-75 wings and no forward elevators. In this configuration, it was widely publicized as The Flying Fish.

At first, Flying-boat No.2 would not leave the water; the hydrodynamic drag of the hull prevented it from reaching flying speed. After observing the difficulty from an accompanying motorboat, Curtiss suggested breaking the smooth line of the bottom with a step just behind the centre of gravity.

Incorporation of the hydroplane step had two beneficial effects. First, it removed nearly half the length of the hull from contact with the water at near-take off speeds; second, it permitted a degree of rotation at take off speed to allow the wings to reach the higher angle of attack needed for take off. Too much rotation, however, put the rear of the hull back in the water and the added drag killed the take off speed. The step worked so well that Curtiss patented it, along with vents that allowed air to bleed into the water cavity behind the step to further reduce drag at take off speed.

Fitted with the step, Flying-boat No.2 made its first flight in July 1912.

Following the perfection of the hydro aeroplane or seaplane, which was simply a landplane with floats substituted for wheels, Curtiss sought to develop a true flying-boat. The distinction lay in the fact that the boat-like hull formed an integral part of the structure rather than being an interchangeable accessory as on the hydro. Although others were working on the same idea concurrently, Glenn Curtiss is recognized as the inventor of the aeroplane configuration known as the flying-boat. The basic layout that he developed in 1912 became the world standard for single-engined flying-boats and is still being used.

Flying-boat No.1. The first Curtiss flying-boat, tried at San Diego on 10 January, 1912, was more a hydro than a true boat. A wide hull, only slightly longer than the standard Curtiss pontoon, was attached under the lower wing of the de-engined airframe of the tractor seaplane. A single 60 hp engine was mounted in the hull and drove two tractor propellers through chains in Curtiss's only deliberate adaptation of a Wright brothers' feature. There were two side-by-side seats in a cockpit behind the wing.

Although No.1 was unable to take off, the experiment did indicate that the flying-boat concept was practicable. Subsequent developments were made at Hammondsport.

Flying-boat No.2, The Flying Fish. The first successful flying-boat, built at Hammondsport, featured a full-length flat-bottomed hull that supported both the wings and tail. To keep the horizontal tail surfaces out of the water, they were sited part-way up the long vertical fin.

The engine was a 75 hp Curtiss Model O installed between the wings as on standard pushers. An indication of the fact that Flying-boat No.2 was built quickly and cheaply to prove a concept rather than to achieve optimum performance is shown by the initial use of an old set of 1910-style single surface wings. Forward elevators were also fixed to the bow at a time when they were being omitted from production aeroplanes. Flying-boat No.2 underwent considerable modification and refinement within a short period, ending up with double surface E-75 wings and no forward elevators. In this configuration, it was widely publicized as The Flying Fish.

At first, Flying-boat No.2 would not leave the water; the hydrodynamic drag of the hull prevented it from reaching flying speed. After observing the difficulty from an accompanying motorboat, Curtiss suggested breaking the smooth line of the bottom with a step just behind the centre of gravity.

Incorporation of the hydroplane step had two beneficial effects. First, it removed nearly half the length of the hull from contact with the water at near-take off speeds; second, it permitted a degree of rotation at take off speed to allow the wings to reach the higher angle of attack needed for take off. Too much rotation, however, put the rear of the hull back in the water and the added drag killed the take off speed. The step worked so well that Curtiss patented it, along with vents that allowed air to bleed into the water cavity behind the step to further reduce drag at take off speed.

Fitted with the step, Flying-boat No.2 made its first flight in July 1912.

The first successful Curtiss flying-boat was assembled and flown at Hammondsport using an old set of single-surface wings and a forward elevator.

Other Experimental Flying-boats

Several other flying-boats were built immediately after No.2 to try different hull designs, engine positions and other features. They carried no known designations and their constant modifications have complicated the identification problem. Three are described here.

Freak Boat/C-1/AB-1. Identified only as 'Freak Boat' in later Curtiss photographic records, this 'boat had a full-length hull but the pilots were in the open as on the standard hydro. The close gap of the equal-span wings lowered the upper wing to the top of the pusher engine. The horizontal tail was mounted on struts above the hull and the square rudder was used without a vertical fin.

After extensive modification that included entirely new tail surfaces and shorter unequal-span wings, this 'boat was sold to the Navy in November 1912, and designated C-1. In March 1914, the designation was changed to AB-1. As C-1, it made the first successful catapult launch of a flying-boat on 12 December, 1912, at Washington Navy Yard. Its last flight was on 1 April, 1914.

Tadpole. Identified only as Tadpole, this flying-boat is representative of several that had their hulls built in the form of elongated main hydro floats with the area between the top of the float and the wings built up with a light fabric-covered superstructure. On Tadpole, the tail surfaces were carried above the hull on struts. The wing assembly pivoted about the rear spar to provide a variable-incidence feature; the pusher engine was stabilized by a tie rod between the end of the propeller shaft and the tail surfaces.

A-2/OWL/E-1/AX-1. The A-2 was the Navy's second aeroplane, a Curtiss Model E delivered as a landplane on 13 July, 1911. The original engine was a four-cylinder 50 hp model, soon changed to a 60 hp V-8.

The A-2 was converted to a seaplane in June 1912. It was further modified at Hammondsport in October 1912 to enclose the crew in a fabric-covered superstructure between the float and the wings, eliminating the interchangeability feature and making the A-2 a short-hull flying-boat. Further experimentation added retractable wheels to give amphibian capability; the unofficial designation of OWL was applied to signify operation 'over water and land'. The Navy designation was changed to E-1 in September 1913 and finally to AX-1 in March 1914. It was wrecked on 27 November, 1915, after 91 flights.

Testing of the experimental flying-boats of 1912 soon resulted in a marketable design. The earliest production versions, which were undesignated, had hulls with strong lower structure and a light upper superstructure filling the underwing gap and enclosing the two-man crew. Wings, with interplane ailerons, were sometimes of equal span and sometimes had extended upper wingtips. The design culminated in the Model F, which was immediately popular and enjoyed wide sale to private owners in the United States and to foreign governments.

Several other flying-boats were built immediately after No.2 to try different hull designs, engine positions and other features. They carried no known designations and their constant modifications have complicated the identification problem. Three are described here.

Freak Boat/C-1/AB-1. Identified only as 'Freak Boat' in later Curtiss photographic records, this 'boat had a full-length hull but the pilots were in the open as on the standard hydro. The close gap of the equal-span wings lowered the upper wing to the top of the pusher engine. The horizontal tail was mounted on struts above the hull and the square rudder was used without a vertical fin.

After extensive modification that included entirely new tail surfaces and shorter unequal-span wings, this 'boat was sold to the Navy in November 1912, and designated C-1. In March 1914, the designation was changed to AB-1. As C-1, it made the first successful catapult launch of a flying-boat on 12 December, 1912, at Washington Navy Yard. Its last flight was on 1 April, 1914.

Tadpole. Identified only as Tadpole, this flying-boat is representative of several that had their hulls built in the form of elongated main hydro floats with the area between the top of the float and the wings built up with a light fabric-covered superstructure. On Tadpole, the tail surfaces were carried above the hull on struts. The wing assembly pivoted about the rear spar to provide a variable-incidence feature; the pusher engine was stabilized by a tie rod between the end of the propeller shaft and the tail surfaces.

A-2/OWL/E-1/AX-1. The A-2 was the Navy's second aeroplane, a Curtiss Model E delivered as a landplane on 13 July, 1911. The original engine was a four-cylinder 50 hp model, soon changed to a 60 hp V-8.

The A-2 was converted to a seaplane in June 1912. It was further modified at Hammondsport in October 1912 to enclose the crew in a fabric-covered superstructure between the float and the wings, eliminating the interchangeability feature and making the A-2 a short-hull flying-boat. Further experimentation added retractable wheels to give amphibian capability; the unofficial designation of OWL was applied to signify operation 'over water and land'. The Navy designation was changed to E-1 in September 1913 and finally to AX-1 in March 1914. It was wrecked on 27 November, 1915, after 91 flights.

Testing of the experimental flying-boats of 1912 soon resulted in a marketable design. The earliest production versions, which were undesignated, had hulls with strong lower structure and a light upper superstructure filling the underwing gap and enclosing the two-man crew. Wings, with interplane ailerons, were sometimes of equal span and sometimes had extended upper wingtips. The design culminated in the Model F, which was immediately popular and enjoyed wide sale to private owners in the United States and to foreign governments.

The Freak Boat of 1912 had such a small wing gap that the engine had to be mounted near the upper wing. After extensive modification, this machine was sold to the US Navy as C-1.

A later and more refined Curtiss flying-boat, known only as the Tadpole, taking off at Hammondsport.

Model F

1913 Model. The 1913 Model F used the early composite hull construction and what were essentially Model E-75 wings with strut-braced extensions of the upper wing. Because of its many 'old' features relative to the 1914 F-boat, the 1913 model has sometimes (and erroneously) been referred to by historians as the E-boat in disregard of the recognized Curtiss Model E landplane and the Navy's E-designation.

Model F (1913)

Two seats.

Span 41 ft 8 in (12.69 m); length 27 ft 4 in (8.33 m).

Gross weight 1,760 lb (798 kg).

Maximum speed 54.8 mph (88.19 km/h); climb 1,200 ft (365 m) in 7.6 min; endurance 4 hr.

Powerplant 75 hp Curtiss O.

1914 Model. The standardized Model F of 1914 differed noticeably from the 1913 versions, particularly in having equal-span wings with rounded tips projecting beyond the end struts and a hull with full-depth primary structure and a rounded wood veneer foredeck. On some civil models, the foredeck hinged forward to form a gangplank for crew movement to or from a beach. An additional feature was a diagonal strut from the engine mount to the lower forward hull structure, intended to protect the crew from a falling engine in a crash. This became known as the Goodier strut since it was installed as the result of Army Lt Lewis Goodier's crash in the Army's first F-boat, S.C.15.

US Navy C-1/C-5 (AB-l/5). The Navy bought five early flying-boats from Curtiss and designated them Navy Type C. Numbering was in sequence of delivery, but the 'boats were not identical, ranging from one of the experimentals modified to near-production standard (C-1/AS-1) to the stock F-boat. On 30 August, 1913, the C-2 flew at Hammondsport under the complete control of a Sperry gyroscopic automatic pilot. The C-boats were redesignated as ABs with the same sequential numbers on 25 March, 1914.

The AB-3 became the first US military aircraft to see action. It was transported with AH-3 to Vera Cruz, Mexico, aboard the cruiser Birmingham, arriving on 21 April, 1914. On 25 April, Lt P. N. L. Bellinger piloted AB-3 on a reconnaissance mission over the city of Vera Cruz and surveyed the harbour for mines. AB-3 later had its wings shortened and was used as a non-flying 'Penguin' taxying-trainer.

US Army 15, 34, 49. The three Curtiss flying-boats delivered to the Army between November 1912 and December 1915, were identified in service only by their Signal Corps numbers. In detail they ranged from composite-hull 'E-boat' (No.15) to the standardized 1914 model mahogany-bull F-boat (Nos 34, 49).

Model F (Revised)

The basic single-engine pusher-type F-boat of 1913-14 was ordered in small numbers by the Navy to the end of 1916. After US entry into the war in 1917, orders were increased when the design was chosen as the Navy's standard primary training flying-boat; 144 were procured after April 1917 and production continued into 1918 until replaced by the MF, yet the F was overlooked in the 1935 redesignation.

The 1917-18 Model Fs were greatly improved over the 1914 model, the principal change being redesign of the control system to delete the shoulder-yoke aileron control, both Services having agreed to standardize on the Deperdussin system in August 1916. Various wing modifications were tried on a few examples, among them extension of the upper wing span to 45 ft 1 3/8 in (13,75 m) and transfer of the interplane ailerons to the upper wing. Several F-boats were fitted out as aerial ambulances, with provision for a litter to be carried on top of the hull behind the cockpit. Powerplant was the 100 hp Curtiss OXX-3.

Costing $7,500, less GFE, new, surplus F-boats came on the postwar market priced at $1,750 and saw relatively wide use by private owners. US Navy serial numbers: A145, A146, A386, A387, A390/393 (4), A408, A752/756 (5), A2279/2281 (3), A2295/2344 (50), A3328/3332 (5), A4079/4108 (30), A4349/4402 (54), A5258

Revised 1917 Model F

Trainer flying-boat. Two pilots.

100 hp Curtiss OXX-3.

Span 45 ft 1 3/8 in (13,75 m); length 27 ft 9 3/4 in (8,47 m); height 11 ft 2 13/16 in (3,42 m); wing area 387 sq ft (35,95 sq m).

Empty weight 1.860 lb (843,68 kg); gross weight 2,460 lb (1.115,83 kg).

Maximum speed 69 mph (111 km/h); climb to 2,300 ft (701 m) 10 min; service ceiling 4,500 ft (1.372 m); endurance 5,5 hr at cruising speed.

Model K (Model 4)

The Model K of 1915 was a logical development of the popular Model F flying-boat. It was larger, more refined in detail, and was powered with a 150 hp Curtiss V-X engine in the now traditional between-wings pusher location. Other than size, the distinctive differences between the F and the K were the heavy stagger of the K wings, the use of ailerons inset into the upper wing, and a V-bottom for the hull.

The K-boats did not sell well in the US but enjoyed a brisk export trade. Some, sold to Russia and delivered after many delays, were unseaworthy when set up because they had lain in their shipping crates so long that their wooden hulls had dried out and opened up numerous cracks.

Model K

Three-seat military flying-boat. 150 hp Curtiss V-X.

Span 55 ft 9 7/8 in (17,01 m); length 31 ft 5 1/4 in (9,58 m); wing area 592 sq ft (54,99 sq m).

Empty weight 2,700 lb (1,225 kg); gross weight 3,900 lb (1,769 kg) .

Maximum speed 70 mph (112,65 km/h); rate of climb 150 ft/min (0,76 m/sec); range 364 miles (586 km).

1913 Model. The 1913 Model F used the early composite hull construction and what were essentially Model E-75 wings with strut-braced extensions of the upper wing. Because of its many 'old' features relative to the 1914 F-boat, the 1913 model has sometimes (and erroneously) been referred to by historians as the E-boat in disregard of the recognized Curtiss Model E landplane and the Navy's E-designation.

Model F (1913)

Two seats.

Span 41 ft 8 in (12.69 m); length 27 ft 4 in (8.33 m).

Gross weight 1,760 lb (798 kg).

Maximum speed 54.8 mph (88.19 km/h); climb 1,200 ft (365 m) in 7.6 min; endurance 4 hr.

Powerplant 75 hp Curtiss O.

1914 Model. The standardized Model F of 1914 differed noticeably from the 1913 versions, particularly in having equal-span wings with rounded tips projecting beyond the end struts and a hull with full-depth primary structure and a rounded wood veneer foredeck. On some civil models, the foredeck hinged forward to form a gangplank for crew movement to or from a beach. An additional feature was a diagonal strut from the engine mount to the lower forward hull structure, intended to protect the crew from a falling engine in a crash. This became known as the Goodier strut since it was installed as the result of Army Lt Lewis Goodier's crash in the Army's first F-boat, S.C.15.

US Navy C-1/C-5 (AB-l/5). The Navy bought five early flying-boats from Curtiss and designated them Navy Type C. Numbering was in sequence of delivery, but the 'boats were not identical, ranging from one of the experimentals modified to near-production standard (C-1/AS-1) to the stock F-boat. On 30 August, 1913, the C-2 flew at Hammondsport under the complete control of a Sperry gyroscopic automatic pilot. The C-boats were redesignated as ABs with the same sequential numbers on 25 March, 1914.

The AB-3 became the first US military aircraft to see action. It was transported with AH-3 to Vera Cruz, Mexico, aboard the cruiser Birmingham, arriving on 21 April, 1914. On 25 April, Lt P. N. L. Bellinger piloted AB-3 on a reconnaissance mission over the city of Vera Cruz and surveyed the harbour for mines. AB-3 later had its wings shortened and was used as a non-flying 'Penguin' taxying-trainer.

US Army 15, 34, 49. The three Curtiss flying-boats delivered to the Army between November 1912 and December 1915, were identified in service only by their Signal Corps numbers. In detail they ranged from composite-hull 'E-boat' (No.15) to the standardized 1914 model mahogany-bull F-boat (Nos 34, 49).

Model F (Revised)

The basic single-engine pusher-type F-boat of 1913-14 was ordered in small numbers by the Navy to the end of 1916. After US entry into the war in 1917, orders were increased when the design was chosen as the Navy's standard primary training flying-boat; 144 were procured after April 1917 and production continued into 1918 until replaced by the MF, yet the F was overlooked in the 1935 redesignation.

The 1917-18 Model Fs were greatly improved over the 1914 model, the principal change being redesign of the control system to delete the shoulder-yoke aileron control, both Services having agreed to standardize on the Deperdussin system in August 1916. Various wing modifications were tried on a few examples, among them extension of the upper wing span to 45 ft 1 3/8 in (13,75 m) and transfer of the interplane ailerons to the upper wing. Several F-boats were fitted out as aerial ambulances, with provision for a litter to be carried on top of the hull behind the cockpit. Powerplant was the 100 hp Curtiss OXX-3.

Costing $7,500, less GFE, new, surplus F-boats came on the postwar market priced at $1,750 and saw relatively wide use by private owners. US Navy serial numbers: A145, A146, A386, A387, A390/393 (4), A408, A752/756 (5), A2279/2281 (3), A2295/2344 (50), A3328/3332 (5), A4079/4108 (30), A4349/4402 (54), A5258

Revised 1917 Model F

Trainer flying-boat. Two pilots.

100 hp Curtiss OXX-3.

Span 45 ft 1 3/8 in (13,75 m); length 27 ft 9 3/4 in (8,47 m); height 11 ft 2 13/16 in (3,42 m); wing area 387 sq ft (35,95 sq m).

Empty weight 1.860 lb (843,68 kg); gross weight 2,460 lb (1.115,83 kg).

Maximum speed 69 mph (111 km/h); climb to 2,300 ft (701 m) 10 min; service ceiling 4,500 ft (1.372 m); endurance 5,5 hr at cruising speed.

Model K (Model 4)

The Model K of 1915 was a logical development of the popular Model F flying-boat. It was larger, more refined in detail, and was powered with a 150 hp Curtiss V-X engine in the now traditional between-wings pusher location. Other than size, the distinctive differences between the F and the K were the heavy stagger of the K wings, the use of ailerons inset into the upper wing, and a V-bottom for the hull.

The K-boats did not sell well in the US but enjoyed a brisk export trade. Some, sold to Russia and delivered after many delays, were unseaworthy when set up because they had lain in their shipping crates so long that their wooden hulls had dried out and opened up numerous cracks.

Model K